Gnosticism: A Hinge Profile

So, to recap, Gnosticism:

- involved a good-evil dualism that was frequently also a spirit-matter dualism

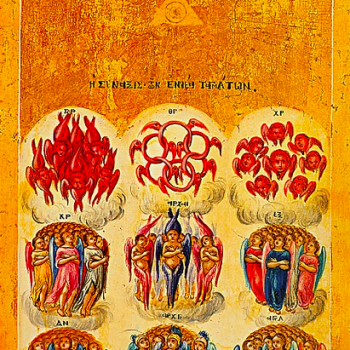

- tended to believe in complicated hierarchies of deities or angels, one of which was typically the fallen creator of matter

- offered liberation from evil primarily in terms of secret knowledge and post-mortem escape from the world, not forgiveness of sins or final resurrection

- did not accept Christian doctrines like the Incarnation, the Passion, or the efficacy of sacraments

- tended to distinguish between a predestined spiritual elite, who were capable of enlightenment, and a greater mass of humanity who were not

- tended to encourage an ascetic moral code (e.g., mostly avoiding sex, violence, and alcohol)1

As mentioned before, Gnosticism was more a set of themes than a coherent school of thought. There were lots of specific incarnations of it, and their beliefs often contradicted each other. And again, this was for the most part a second-century movement. There were religions like Manichæism that were obviously akin in both beliefs and sources; there were later sects that hit upon similar themes, notably the Cathars2; but Gnosticism, properly so called, was a phenomenon of the pre-Constantine Roman Empire.

So where do modern people get off calling this and that and the other thing “Gnosticism”?

The Terms of the Problem

The short answer is: a lot of people are imaginative, ignorant, vain, and lazy, all at the same time and in varying proportions. These qualities become relevant to this conversation when you:

- hand somebody a fancy term that sounds smart—e.g., “Gnosticism”;

- tell them it’s important and give them a very basic sketch of its meaning; and

- turn them loose with no further restraint or information.

This isn’t new, of course. Technical terms are always abused this way—Catholic apologists have much to answer for on this front.3 And in this way, calling things “Gnosticism” when they’re not is unremarkable; if the buzzword weren’t “Gnosticism” it’d be something else, and it often has been. The internet is also partly to blame: it’s always been easy to tear facts out of their context, or to present theories as if they were facts, but with modern tech, these irresponsible tactics can be shared with millions of people literally instantaneously. (These tools make verification easier than it used to be too, but cf. “most of us are lazy” above.)

What is a little bit strange, and a lot bit annoying, is that something we may loosely call “Gnostic spirituality” is real, and is a bad thing. It just has nothing to do with any of the stuff being labeled Gnostic. The modern crew of intellectuals who feel entitled to join the Inquisition before receiving instruction for baptism are, surprise surprise, often wrong.4 But what is this amorphous thing, about which I keep just saying “Not like that!” while waving my hands in a general right-ward direction?

Gnostic Spiritualities

Starting from some common doctrines of the extinct Gnostic sects, we can identify a few theological and spiritual themes that may genuinely edify us. I see five as specially relevant to modern culture:

- Dualism: there are, and can be, no shades of moral grey.

- Apocalypticism: what I do is good because I’m on the side of good; my enemies are evil because what they do serves the side of evil.

- Pseduo-Docetism: sexuality is trivial.

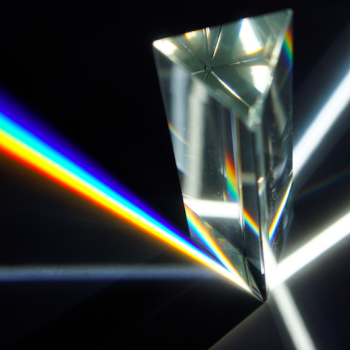

- Gnosis: orthodoxy constitutes holiness/salvation.

- Election: personal enlightenment/autonomy trumps the authority of the Church.

All of these have superficial expressions, typically on both “sides” of the culture war. But looking at these things through the lens of Gnosticism doesn’t actually teach us much. Unduly black-and-white moral views aren’t unique to Gnosticism, or even to religious people generally. And a lot of folks have pointed at the more bizarre aspects of Scientology as a modern parallel to Gnosticism5: fine; so what?

But I do think there are certain elements in American culture—both inside and outside Christian circles—which do stand out and make more sense if we set them beside Gnosticism. Let’s take the five points above, one by one, and dig a little deeper.

Footnotes

1This often included vegetarianism. Today, we tend to associate vegetarianism and veganism with opposition to animal cruelty. This aligns, vaguely, with the Indic principle of ahimsā or complete nonviolence (shared by Hindus, Jains, and Buddhists); this may have developed from or been influenced by the doctrine of reincarnation.

Vegetarianism in ancient and medieval Europe was rather different. Some ancient schools adopted it simply as a specific type of fasting—this was common among early monastics. However, the Gnostics (and later groups with similar beliefs) abstained from meat because it came from sexual reproduction.

As for alcohol, besides the ascetic motive of “giving up this fun thing” and the prudential motive of “giving up this thing that can make you act stupid,” I can’t say why some religions go in for teetotalism. Maybe those two motives are all there really is to it.

2The Cathars (from the Greek katharoi or “the pure”) were a heresy common in the High Medieval period, principally in southern France, whose city of Albi gave them their other name of Albigenses. The Albigensian Crusade was a holy war proclaimed against precisely these heretics, and, predictably, involved some of the ugliest moments and maxims in Catholic history.

3As do Protestant apologists. However, given that the raison d’être of so many Protestants is an explicit distrust of, or at least wariness about, clerical expertise and authority, there is far more excuse for them than for the Catholics.

4It might be rude to cite examples like James Lindsay and Jordan Peterson here. Possibly very rude. Exceedingly, perhaps, rude.

5In my opinion, the most exact modern heir of Gnosticism is the infamous Heaven’s Gate cult, whose members almost all committed mass suicide in 1997. The hostile archons of some Gnostic sects—devil-like beings which rule the planets and try to prevent humans from ascending to the Godhead by trapping us in the material realm—show an eerie affinity with the malicious aliens some cults believe in. To a superstitious person like me, the traditional belief that human ideas are partly guided by the Powers, some of which are fallen, inevitably springs to mind …