So, picking up from last time:

Acts 15:1-2, 3-21, 22-29, RSV-CE

But some men came down from Judea and were teaching the brethren, “Unless you are circumcised according to the custom of Moses, you cannot be saved.” And when Paul and Barnabas had no small dissension and debate with them, Paul and Barnabas and some of the others were appointed to go up to Jerusalem to the apostles and the elders about this question. So, being sent on their way by the church, they passed through both Phoenicia and Samaria, reporting the conversion of the Gentiles, and they gave great joy to all the brethren. When they came to Jerusalem, they were welcomed by the church and the apostles and the elders, and they declared all that God had done with them. But some believers who belonged to the party of the Phariseesa rose up, and said, “It is necessary to circumcise them, and to charge them to keep the law of Moses.”

The apostles and the elders were gathered together to consider this matter. And after there had been much debate, Peter rose and said to them, “Brethren, you know that in the early days God made choice among you, that by my mouth the Gentiles should hear the word of the gospel and believe. And God who knows the heart bore witness to them, giving them the Holy Spirit just as he did to us; and he made no distinction between us and them, but cleansed their hearts by faith. Now therefore why do you make trial of God by putting a yoke upon the neck of the disciples which neither our fathers nor we have been able to bear? But we believe that we shall be saved through the grace of the Lord Jesus, just as they will.”

And all the assembly kept silence; and they listened to Barnabas and Paul as they related what signs and wonders God had done through them among the Gentiles. After they finished speaking, Jamesb replied, “Brethren, listen to me. Symeon has related how God first visited the Gentiles, to take out of them a people for his name. And with this the words of the prophets agree, as it is written,

‘After this I will return,

and I will rebuild the dwelling of David, which has fallen;

I will rebuild its ruins,

and I will set it up,

that the rest of men may seek the Lord,

and all the Gentiles who are called by my name,

says the Lord, who has made these things known from of old.’

Russian ikon of St. James the Less, 16th c.

Therefore my judgment is that we should not trouble those of the Gentiles who turn to God, but should write to them to abstain from the pollutions of idols and from unchastity and from what is strangled and from blood.c For from early generations Moses has had in every city those who preach him, for he is read every sabbath in the synagogues.”d

Then it seemed good to the apostles and the elders, with the whole church, to choose men from among them and send them to Antioch with Paul and Barnabas. They sent Judas called Barsabbas, and Silas, leading men among the brethren, with the following letter: “The brethren, both the apostles and the elders, to the brethren who are of the Gentiles in Antioch and Syria and Cilicia,e greeting.f Since we have heard that some persons from us have troubled you with words, unsettling your minds, although we gave them no instructions, it has seemed good to us in assembly to choose men and send them to you with our beloved Barnabas and Paul, men who have risked their livesg for the sake of our Lord Jesus Christ. We have therefore sent Judas and Silas, who themselves will tell you the same things by word of mouth. For it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us to lay upon you no greater burden than these necessary things: that you abstain from what has been sacrificed to idols and from blood and from what is strangled and from unchastity. If you keep yourselves from these, you will do well. Farewell.”f

Acts 15:1-2, 3-21, 22-29, my translation

Now, some people who came from Judea were teaching the brothers that “Unless you are circumcised according to the custom of Moshe, you cannot be saved.” There came to be unrest, and not a few disputes with Paul and bar-Nevua’ against them; they arranged for Paul and bar-Nevua’ and some others from among them to go up to the emissaries and elders in Jerusalem about this question.

18th-c. ikon of St. Paul the Apostle.

So they were sent forth by the assembly and went through Phoenicia and Samaria; they described the conversion of the nations, and gave great joy to all the brothers. Coming into Jerusalem, they were received by the assemblies, emissaries, and elders, and brought news of what God had done through them. But some people who were from the sect of the Phariseesa who had believed were saying that “It is necessary to circumcise them and instruct them to observe the Law of Moshe.” And the emissaries and elders were brought together to see about this idea.

After there had been much dispute, Rocky rose and said to them: “Men and brothers, you understand that from the old days among you, God selected that through my mouth, the nations should hear the word of the good news and believe; and God, who knows hearts, bore witness to them, giving them the Holy Spirit just as he did to us also, and he did not discriminate between ourselves and them, having cleansed their hearts by belief. Now, then, is anyone trying God, to put a yoke on these students’ necks which neither our fathers nor we have had the strength to carry? But by the grace of the Lord Jesus, we believe, to be saved—in which manner, these others will too.”

The whole crowd was silent, and listened to bar-Nevua’ and Paul relating the things God had done through them, signs and miracles among the nations. After the silence, Jacobb replied to them, saying: “Men and brothers, listen to me. Symeon related just how at first God visited him to take from the nations a people unto his name. And in this, the words of the prophets are of one voice, just as it is written: ‘”After these things I will turn and re-pitch the tent of David that has fallen down, and her things that have been demolished I will re-pitch and set upright again, so that those left over will inquire after the Lord, and every nation will invoke my name upon themselves,” says the Lord, who does things known from an age ago.’ Because of this, I judge we should not harass those of the nations who have turned to God, but should send word to them to stay away from the pollutions of idols, and from sexual sin, and from the strangled and blood.c For Moshe from old generations has his heralds from one city to the next, being read in the synagoguesd every sabbath.”

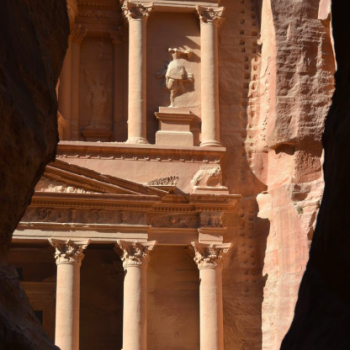

The Alte Synagoge (Old Synagogue) in Erfurt,

Germany, the oldest synagogue in Europe—

parts date to the 12th c. Photo by Michael Sander,

used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

Then it seemed good to the emissaries and the elders, with the whole assembly, to select men from among them to send to Antioch with Paul and bar-Nevua’, Judah called bar-Tzaba and Silas, leading men among the brothers, having written by hand as follows:

“The emissaries and elder brothers, to the brothers from Antioch, Syria, and Ciliciae who are of the nations: Hail.f

“Since we have heard that some of us went out and troubled you with words that unsettled your lives, which we did not admonish them to, it seemed good to us, having reached unanimity, to select men and send them to you along with our beloved bar-Nevua’ and Paul, people who have put their lives at stakeg for the name of our Lord Jesus the Anointed. So we have commissioned Judah and Silas, announcing these things to them by word. For it seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us to put no further weight on you than these necessities—stay away from things offered to idols, blood, and what has been strangled, and from sexual sin; if you guard yourselves carefully against these things, you will do well.

“Farewell.”f

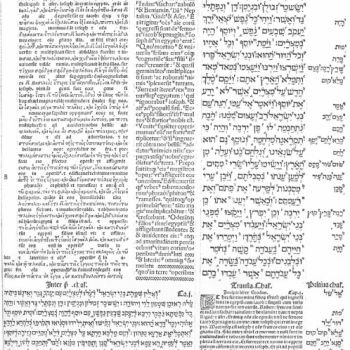

The first four canons from a 1715 annotated

edition of the Canons of the Apostles,

a Syrian appendix to the 4th-c. Apostolic

Constitutions (a book of church order).

Textual Notes

a. of the party of the Pharisees/from the sect of the Pharisees | τῆς αἱρέσεως τῶν Φαρισαίων [tēs haireseōs tōn Farisaiōn]: The linguistic matter I want to highlight here is in the Greek rather than the English; it lies in the word αἱρέσεως (whose dictionary form is αἵρεσις [hairesis]). But its most famous descendant is the term “heresy.”

Dan Brown would have us believe that αἵρεσις comes from αἱρέω [haireō], meaning “to choose,” and that “heresy” was originally a slur thrown by Catholics at people who chose how to think, instead of following the Catholic Magisterium1 blindly. Dan Brown is incorrect—or rather, he’s right that αἵρεσις comes from αἱρέω (which has several senses besides “to choose”). But subscribing to Christian orthodoxy is just as much a decision as subscribing to anything else; and in any case it’s unclear to me why we should be prejudiced in favor of people choosing what their religious beliefs are, as if “choice” were an admirable phenomenon in itself rather than “a description of most of the things human beings do while awake.”

The genuinely relevant fact is that αἱρέσεις [haireseis] was a standard term for “parties” of various sorts, especially in the religious and philosophical worlds. In the first century CE, secular philosophy fell into four chief αἱρέσεις: i) the Epicureans, who really were not hedonistic—more like Buddhists in Græco-Roman dress; ii) the Middle Platonists, who were eclectic, religiously-inclined thinkers who rejected the skepticism that once dominated the Academy2; iii) the Pyrrhonists, a distinct variety of skepticism; and iv) the Stoics, by far the largest group and the most widely respected of the four.

The site of Plato’s Academy today. Photo by

Wikimedia contributor Tomisti, used under

a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

Templar Judaism also fell into four principal theological factions at the time, although this was just happenstance—its four have nothing to do with the αἱρέσεις of pagan philosophy. They were the Pharisees, the Sadducees, the Essenes, and the Hellenists. (You may have been expecting the Zealots here, but these were more of a political party than a doctrinal or halakhic one.)

The Pharisees were the doctrinal ancestors of rabbinic Judaism; they formed the largest group and had sub-movements among themselves. The Sadducees were an aristocratic, comparatively skeptical party drawn almost exclusively from the priesthood, recognizing a far narrower Biblical canon than the Pharisees—which they could well afford to do, since they were concerned with the Temple and not the synagogue. Only these two sects were present on the Sanhedrin, the supreme religious court. I don’t know if a rule existed against admitting Essenes onto the Sanhedrin, but there probably didn’t need to be: They considered the temple system hopelessly corrupt, mostly led ascetic lives at the fringes of Jewish society, and were in any case not numerous.

Mosaic from a synagogue in Sepphoris, a city

less than four miles from Nazareth. Photo by

Oren Rozen, used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license

(source).

As for the Hellenists, these were primarily a cultural rather than a theological grouping; they were the Jews of the Mediterranean diaspora, whose mother-tongue was Greek rather than Aramaic, and whose Bible was the famous Septuagint. Most would, in all likelihood, have resembled the Pharisees more than the Sadducees or Essenes. But, besides cultural differences, they probably showed a greater and more direct Platonic influence on their faith; certainly we see this in Philo of Alexandria, one of the best-known Hellenist Jews.

This analogy is very imperfect, and must be read only with that precaution in mind. But I think the reader will perhaps get a decent picture of these sects if they imagine first-century Palestine as a little like Georgian Britain. The Church of England will do for our Pharisaic analogue, as the mainstream religious body. There are also a certain number of deists (or even, gasp, atheists) among the aristocracy, à la the Sadducees. Here and there one finds recusant Catholic families, hidden away like Essenes with their old-fashioned, weird practices and ideas; and finally, to stand in for the Hellenists, there are members of the Church of England from the North American colonies. They are Anglicans in good standing, sure; but they exhibit perspectives and opinions, and a certain manner, that—while licit in theory, maybe—would eventually lead someone saying something like, “She just wouldn’t do as the wife of the future Bishop of Lichfield.”

Papyrus 20, a third-century fragment of a

manuscript of James; this side contains most

of vv. 3-9 of chapter 3.

b. James/Jacob | Ἰάκωβος [Iakōbos]: The Bible is less full of Jameses/Jacobs than of Maries/Miriams, but it has its share.1 This is James the son of Alphæus, the one known as “St. James the Less”; this probably means he was the younger of the two Jameses among the Twelve, but possibly that he was the shorter. (St. James the Greater, James bar-Zebedee, had already been martyred—see Acts 12.) St. James the Less is also traditionally, though not unanimously, identified with all of the following:

- James the son of Clopas or Cleophas

- James the brother of the Lord

- James the Just

- the author of the Epistle of James

Some scholars theorize that Alphæus, Cleophas, and Clopas are all be attempts at representing the Hebrew name חַלְפַּי [Ḥalpay], or an Aramaic name derived from it, in Greek. As far as I can tell, the hypothesis has gained general acceptance.

Alphæus as imagined by Lucas Cranach the Elder.

Part of one panel from his Torgau Altarpiece

(1509), a triptych showing the Holy Family and

additional kinsmen of Mary’s.

The expression “brother of the Lord” poses us a puzzle, given the doctrine that the Mother of God a virgin not only when she gave birth to Jesus, but perpetually. “Brothers of the Lord” is therefore interpreted by most Catholic and Orthodox commentators as an allusion to cousins. Aramaic and Hebrew lack a distinct term for “cousin”; Greek does have one, ἀνεψιός [anepsios], but the term can also mean “nephew,”2 and in any case, ἀνεψιός would not be a natural translation of אֲחָא [‘àḥâ’], “brother,” the Aramaic word presumably used by, e.g., the Nazarene villagers from Mark 6:3. There are also a minority of Catholic and Orthodox scholars who interpret Jesus’ siblings as stepsiblings—children of St. Joseph from a prior marriage.

I’m slightly more inclined to take the former interpretation than the latter. If they were Jesus’ stepfamily, then St. James the Less et al. would have been older than Jesus; however, James is not supposed to have been martyred until 62 (or in some versions, 69), which would put him in his seventies or eighties at the time of his death. Obviously this is perfectly possible, but it would be uncommon—median life expectancy for those who lived through infancy was somewhere around the mid-sixties—so it seems a little more natural to think these siblings were younger than Jesus, which would likely make James likely somewhere in his fifties at his death. Hence, if we’re accepting the tradition that the Theotokos was perpetually virgin (and we are), the “cousins” explanation is the most economical.

As to how they were related more precisely, one widespread theory here is that Mary the Mother of God and Mary the wife of Clopas were sisters. It may sound ludicrous to suggest that two sisters would have the same name, but this was actually not at all uncommon in the ancient world; distinction, when necessary, would be made by nicknames, not infrequently based on birth order. (In Rome, whose naming conventions were in this respect similar, a household of e.g. the Flavian family that had four daughters would have been perfectly capable of naming all four “Flavia” and addressing them as “Prima,” “Secunda,” “Tertia,” and “Quarta”3 without anybody batting an eye.)

The Presentation in the Temple (1388), Bartolo

di Fredi. St. Joseph is on the left; in the center

are the Virgin, the Infant, and St. Simeon; to the

right is St. Anna; see Luke 2 for details.

Finally, St. James the Less is probably the only James who could have referred to himself simply as “James,” without specification, and be recognizable to Christians elsewhere who did not personally know him. This in turn makes him the most plausible candidate for the authorship of the epistle, unless it is pseudepigraphical—or, in English, forged.

That James is in fact a forgery is a prominent theory, to be fair. However, it’s not an idea I find persuasive. The arguments against its authenticity include such keen observations as “His Greek is pretty good,” clearly an impossible feat for a Jew who had spent his entire life in multi-lingual Palestine—specifically, the northern bit, which literally had the epithet “of the Gentiles.” Or that classic of entirely too much New Testament scholarly conjecture, the what-is-even-your-point-here argument, “He borrowed from I Peter, maybe.” The reason this tells against the letter’s authenticity in the first place is … what? Seriously, why is this an argument? Are we supposed to think the apostles were each concerned to maintain the originality of their “brand”? Though, if we do accept it, it becomes really formidable: The borrowing couldn’t go the other way, you see, because [file not found]. And obviously James (who was from the Galilee) wouldn’t have had any turns of phrase in common with Peter (who by contrast was from the Galilee) inherited from any third source. Not after knowing each other for decades because they had both devoted themselves to, and been trained by, the same rabbi at the same time.

c. from the pollutions of idols and from unchastity and from what is strangled and from blood/from the pollutions of idols, and from sexual sin, and from the strangled and blood | τῶν ἀλισγημάτων τῶν εἰδώλων καὶ τῆς πορνείας καὶ τοῦ πνικτοῦ καὶ τοῦ αἵματος [tōn alisgēmatōn tōn eidōlōn kai tēs porneias kai tou pniktou kai tou haimatos]: The context suggests that these are specifically ritual provisions, designed to promote harmony between Gentile and Jewish Christians without laying an excessive burden on the former. This explains the first two rules, which one would otherwise think would go without saying among Christians whether Gentile or Jewish; “the pollutions of idols” most likely means the meat of animals sacrificed to idols.

A relief of Aphrodite from Aphrodisias (west

of Pisidian Antioch), with the mortal Anchises

and their son Æneas. Photo by Carlos Delgado,

used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

The mention of “the strangled” is probably an extension of the forbidding to eat blood (since an animal killed by strangling would still have the blood in it), whose source lies in Leviticus 17:10-14; note than the next two verses of Leviticus, possibly building on those five, penalize anyone who eats carrion or animals that have died naturally with ritual impurity.

Partly for this reason, the term πορνεία—which literally means “whoring, prostitution,” deriving from πόρνη [pornē], “sex worker, prostitute”—most likely means incest in this context. More specifically, it likely indicates incest as defined by the very next chapter of Leviticus; some translations simply render the term as “unlawful marriage” here. Again, it would go without saying among Christians that they must not practice things like adultery, polygamy (which was in any case illegal under Roman law), concubinage,4 etc. However, the Roman definition of incest was more permissive than that of Jewish culture, and the Greek definition was more relaxed still—Leviticus 18 contains at least ten prohibitions, mostly pertaining to incestuous marriages, that were stricter than those observed by first-century Greeks. (If you were wondering, yes, this probably does explain why some kind of something was going on in Corinth. Although, to be fair to the rest of the Greeks, Corinth had a seedy reputation with the rest of the Empire; a slang term for seeing a prostitute was κορινθιάζομαι [korinthiazomai] or “to Corinthianize”!)

d. synagogues | συναγωγαῖς [sünagōgais]: I’ve departed slightly from my usually-preferred hyper-literalism in this word. The literal meaning is “gatherings” or (by extension) “gathering-places, gathering-houses.” I’m not clear at what point this became the typical Greek term for synagogues. (The Hebrew term קָהָל [qâhâl] or “community” was also used, not only in the Holy Land but in the Diaspora; the Romaniyot and Ladino languages, which are to Greek and Spanish roughly as Yiddish is to German, derived the term kal “synagogue” from this, a word I gather is still used by Romaniotes and at least some Sephardis.) The Greek term was borrowed into Latin, synagōga. This suggests that the Romans became familiar with Jewish houses of worship—familiar enough to perceive that they needed a specialized word, as a distinct kind of thing from temples—either once some Jews were already in the habit of calling these places συναγωγαῖ, or once the Greeks had already begun to use the word with the specific sense “synagogue.”

e. Cilicia | Κιλικίαν [Kilikian]: Cilicia is the area colored red in the map below (off-white is the Roman Empire ca. 106; most of the borders are as near as makes no difference).As it happens, Tarsus, St. Paul’s hometown, is in Cilicia. (Centuries later, during the High Middle Ages, there was an Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, founded by refugees who had fled the Caucasus when the Seljuq Turks invaded.)

Portion of a map by Wikimedia contributor

Milenioscuro, used under a CC BY-SA 4.0

license (source).

f. greeting/hail | χαίρειν [chairein] … Farewell | ἔρρωσθε [errōsthe]: My use of the archaic hail here is not only or even primarily a nod to the Hail Mary. Ancient salutations, whether at the beginning or end of an encounter (be it in person or by letter), were often some form of “in good health”: conventionally, an imperative form. The Latin salutations salvē and valē, pls. salvēte and valēte, from verbs meaning “to be healthy” and “to be strong,” are a typical pair. Technically, Greek did differ slightly (the verb χαίρω [chairō], of which χαίρειν is the infinitive, means “to be glad”), but not very much and not importantly. Likewise, the English hail (the greeting, not the precipitation—that’s just a homophone) meant “Be well,” showing its kinship with its surviving cousins whole and hale. The closing salutation ἔρρωσθε, a rather un-transparent form of the verb ῥώννυμι [rhōnnümi], aligns better with the common pattern, pretty much literally meaning “fare well.”

g. risked their lives/put their lives at stake | παραδεδωκόσι τὰς ψυχὰς αὐτῶν [paradedōkosi tas püschas autōn]: We meet again, παραδίδωμι [paradidōmi]. This is one of those words that is just too useful to mean one thing, and so comes rapidly to mean half a dozen unrelated, frequently incompatible things. Its basic meaning is “to hand over,” which even in English can cover things as unlike each other as the second action of I Corinthians 11:23 and the second (anticipated) action of Matthew 26:15. The wordplay it introduces into many passages, although I find said wordplay entertaining and sometimes illuminating, is therefore likely accidental most of the time.

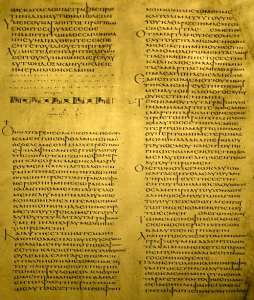

A leaf from Codex Alexandrinus, an uncial5

manuscript from the fourth century that once

contained the whole Bible in Greek.6

Footnotes

1If you’re wondering how English ever managed to take the Hebrew name Ya’aqov and say “James is close enough,” the progression went roughly like this: Hebrew Ya’aqov (יַעֲקֹב [Yaṛàqov]) → Greek Iakōbos (Ἰάκωβος) → Latin Iacomus → Old French/Middle English Iames (pronounced yah-mez or something similar) → Modern English James (pronounced James). This final set of sound-shifts was thanks to three things. First was the invention of the letter j, which started as a mere stylistic variant of i. Second, many Middle English y-sounds (or “palatal approximants”) were fortified into what we now call j-sounds (or … well, to reduce any linguists reading to helpless rage, let’s call them “voiced dental plosives”)—and we now had a letter available to dedicate to that sound. (You can hear a similar change happening in many Spanish dialects; it’s called yeísmo or lleísmo, and turns y, ll, or both into the sounds we usually spell j or zh—but it remains to be seen whether the new sound becomes a standard feature of any dialect of Spanish.) Third and last we have my old arch-nemesis, the Great Vowel Shift: Among other things, this turned a lot of nice open ah-sounds from Middle English into also-lovely, but now confusingly spelled, ey-sounds (that’s ey as in “grey”).

2These meanings may have been conflated in this single word due to the (theorized) Indo-European kinship system, which Greek inherited. A kinship system is the collection of words and concepts used within a language to convey family relationships. English has more distinct terms for the “close family of one’s own generation” category than Aramaic does, as we distinguish between siblings and cousins. Conversely, we have fewer than Mandarin Chinese, which (I gather) has no “plain” words meaning brother or sister—you have to specify whether you mean your older brother or sister or your younger one. Proto-Indo-European used the Omaha kinship system, and that system tends to conflate uncles and cousins. Thus, or so the theory goes, we get the meaning of ἀνεψιός, a bit like that of the Latin nepōs, which can mean either “nephew” or “grandson.” (Modern English, though also derived from proto-Indo-European, descends at a much further remove; we’ve dropped the Omaha system in favor of the Eskimo system.)

3If you feel like you’ve heard the name “Flavian” somewhere before, you are correct—the Flavians were Rome’s second, short-lived, imperial dynasty (Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian). The name Flavia probably meant “blonde”; prima, secunda, tertia, and quarta are simply the first four cardinal numbers in Latin.

4I.e., someone (usually a wealthy man) “keeping” someone else (usually a woman) as a mistress or lover.

5Uncial is a kind of script, associated mainly with Late Antiquity and early Medieval Ireland. To modern eyes, uncials resemble a mix of capital and lower-case letters, as its letter-forms were influenced by both handwriting and inscriptions. Four manuscripts are known as the “great uncial codices” because they originally contained the whole of both Testaments of the Bible in Greek. The four great uncials are Codex Sinaiticus (possibly created in Egypt or Palestine), Codex Alexandrinus (ditto), Codex Vaticanus (probably Italian or Egyptian), and Codex Ephraemi (also likely of, say it with me, Egyptian make).

6Due to some leaves being lost or damaged, Codex Alexandrinus now has omissions from its text of Genesis, Leviticus, I Samuel, Psalms, Sirach, Matthew, John, II Corinthians, and Revelation; the damage is particularly bad in Psalms, II Corinthians, and especially Matthew, nearly all of which has been lost.