Resuming from Chapters One and Two.

Revelation 21:9-10

There came unto me one of the seven angels which had the seven vials full of the seven last plagues, and talked with me, saying, “Come hither, I will shew thee the bride, the Lamb’s wife.” And he carried me away in the spirit to a great and high mountain, and shewed me that great city, the holy Jerusalem, descending out of heaven from God.

At first blush, this might seem like a verse about Christians generally, yet I’m applying to queer people specifically. That is legitimate: What God tells his children, he tells his gay children, ipso facto.

An HDRI photograph of a rainbow.

Photo by Johannes Bahrdt, used under

a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

However, that isn’t what I’m on about here. Rather, I want to highlight this image of the Church—i.e., God’s chosen people as a whole, what our Reformed brethren call “the Church Invisible”—as the Lamb’s Bride.

In a 30-30 thread that I didn’t reproduce here, I discussed an odd detail of the New Testament: It would appear that baptism designates us not merely as God’s children, but specifically as his sons (e.g., in Philippians 4:1-2, St. Paul speaks of “my brethren in the Lord,” but then immediately addresses two women, Euodia and Syntyche1). There’s a legal reason for this. The word firstborn in the Bible is not just an adjective, but a Hebrew legal title. Only an eldest son with no older sisters2 was, in that sense, a firstborn; firstborns were entitled to a larger share of the inheritance than other children, and were expected to fulfill certain social roles others might be excused from. By incorporating us into Christ, the “firstborn of creation” and “firstborn of the dead,” baptism makes us too firstborn sons, whatever our sex or birth order. It’s reminiscent of the story of the daughters of Zelophehad in Numbers 27.

In this passage, the lesson is similar in some ways, but importantly different—namely, we are collectively the bride of Christ. I find this especially worthy of accent, due to a trend in American churches nowadays (one that I suspect is causally connected with Christian homophobia and transphobia, though I’m not sure which is the cause of which). It’s grown popular to complain the church has “become feminized.” This was already going on twenty years ago, before the “Manosphere” stuff fully coalesced in the 2010s; I remember it from when I was in high school, and people were way more normal back then.

In any case, the complaint (whatever its merits or lack thereof) and the Manosphere have cross-fertilized in the worst way, producing a gigantic crop of Christian masc-for-masc grifters—or maybe “grifters” is the wrong word, since many of them may well be sincere, but false teachers and bad influences, whose favorite way of cultivating popularity is playing to the attitudes of adolescent men in their thirties and forties and fifties: men who demand to be excused not only from the beatitudes, the works of mercy, and the Cross, but even from normal maturity. Though really even that doesn’t fully describe the issue—they don’t just want to be excused from the behavior called for by both reason and grace; they want to be admired and praised for refusing these things, in the name of a “manliness” whose only ingredients are ego, self-indulgence, an utter lack of pity, and irrational hostility to anyone unlike themselves.

The New Jerusalem (1860),

by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld.

For once, I find myself agreeing with right-wing alarmists: There is a crisis in masculinity in modern America. That is, there is a crisis in male honesty, modesty, self-control, compassion, gentleness, obedience, and unconditional love. After all, shouldn’t Christians be prepared to take St. Joseph as our model of what a man should behave like? But I digress.

If the Church collectively is in some sense, however metaphorically, feminine, then in that same sense, her male members are as feminine as her female members. And the mere fact that this makes some guys very vocally uncomfortable is kind of weird, by historical standards. Not only is Church-as-bride imagery quite ancient—more ancient than Christianity itself; it is a standard device in the Hebrew Bible—but the soul is treated as feminine throughout both antiquity and the Middle Ages.

Granted, this may be a mere accident of language: the Latin and Greek words most often translated “soul” (anima and ψυχή [psüchē]) are both feminine linguistically; so is the Hebrew נֶפֶשׁ [nefesh], and רוּחַ [ruuaḥ], more commonly rendered “spirit,” can be of either gender.3 But even if it started as simply an artifact of language, it doesn’t seem to have bothered anybody back then; if anything, they leaned in. The mystical poetry of St. John of the Cross is a good example—heavily erotic in its symbolism, and even addressed “to my Husband”! Yet to the best of my knowledge, no one complained of him girling up the place. And it certainly wasn’t that St. John of the Cross lacked enemies. He was imprisoned in brutal conditions for nine months by members of his own order for having the gall to … join an already-approved reform movement and mind his own business (not the Carmelite Order’s finest moment, that4). More probably, our sixteenth-century ancestors would have seen complaints about “feminizing the Church” as sheer nonsense. Like, yes, brides do generally have something femme about them; what’s your point?

To men who take pride in not growing past the mental age of fifteen, making themselves the Lord’s bride likely sounds repellent and threatening. (Just be glad you’re not Mithraists. Everybody thinks it’s so manly getting baptized in bull’s blood, but you do not want to know what νύμφος means.) Even for men more mature than that, it’s a gender-bender.

The thing is, this could be something gay male Catholics might be able to shed some light on for straight male Catholics. You’ll have to deign to view us as people you could learn from, like the Catholic soldier and statesman Dante Alighieri did, if you want to find out. You’ll also have to be ready to listen rather than speak, like St. Joseph did; and willing to admit to yourselves “I was going the wrong way,” and to change to a different one, like the celibate Apostle Paul and the gay World War II veteran Dunstan Thompson did.5

Matthew 5:39, 44-45a

I say unto you, That ye resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also. … I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you; that ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven.

It’s hard to say for sure, but this may be the single most unpopular, deliberately ignored passage in the Gospels. I can only speak from my own experience of course, but in that experience, almost any visibly-religious Catholic (or Orthodox Christian) will—the moment this text or topic come up—change the subject immediately, and nearly always from these words of Christ to the modifications contained in just war theory. This is a little less true of Protestants, since they embrace groups like the Amish and Mennonites with a strong pacifist tradition, but the overall trend holds.

I find this a disquieting symptom. That forgiveness, patience, courtesy, and pity should be unpopular among the paganī,6 the civilians in the Church’s war against depraved trans-dimensional intelligences from the Pit—that much is unremarkable; that Christians (of any stripe) should be so comfortably inattentive to one of Jesus’ most famous sayings as to seem, in some cases, sincerely unaware of it—that is remarkable. Specifically, the remark it provokes is “This is bad.”

Yet even this ignorance is not the worst, stupidest aspect of this. Three things are worse and stupider: first, our long, complacent history of treating what is explicitly a concession as if it were the norm (from which, surely, new concessions must be made); second, a contempt for children as being too stupid to learn what we didn’t wish to believe; and third, the arrogant lie that as Americans, we’ve all sort of absorbed the gospel by osmosis. This dishonest, lazy vanity has brought us so low that in the current culture war, it is consistently Christians—from the ordinary McChurchgoer to the latest hierarchical weirdo with a show called “Saint Hatcast’s: The only FAITH-cast about how to do the life of faith together in real life, that’s also a hat! Tune in Wednesday for much worse jokes, together”—it is consistently Christians who are the loudest, most indignant voices claiming

- that Christians, the US, and the West in general do not sin and have not sinned;

- that people who criticize us are conspiring against our very existence; and

- that ethical precepts like fair play, compassion, humility, truthfulness, and forgetfulness of injuries deserve to be sneered at as losing strategies.

And these claims are advanced not just by ostensible Christians—whose faith is so woven together with redemption from sin that we really ought to be acclimatized to recognizing and admitting our sins, and whose Savior was so unconcerned with “winning” that I can barely understand how strategy comes into ethics at all—but, ostensibly, in the name of said Christianity. Many queer Christians (and others) grew up in households with a faith of this sort, and anyone who did not has surely encountered it since the dawn of the Trumpian GOP.

It is, I think, chiefly to these insufferable pseuds that we will be duty-bound to turn the other cheek, when they smite us on the right. Yes, really. Mostly because, who did you think was going to be smiting us on the right cheek?

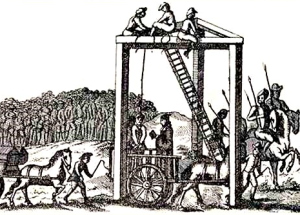

A drawing of the Tyburn Gallows, where many

Christian martyrdoms took place at the hands

of fellow Christians.

I suggest pausing here and saying an Our Father. Say it nice and slow.

Ruth 1:10-12a, 14-17

And they said unto her, “Surely we will return with thee unto thy people.” And Naomi said, “Turn again, my daughters: why will ye go with me? are there yet any more sons in my womb, that they may be your husbands? Turn again, my daughters, go your way …” And they lifted up their voice, and wept again: and Orpah kissed her mother in law; but Ruth clave unto her.

And she said, “Behold, thy sister in law is gone back unto her people, and unto her gods: return thou after thy sister in law.” And Ruth said, “Intreat me not to leave thee, or to return from following after thee: for whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge: thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God: where thou diest, will I die, and there will I be buried: the Lord do so to me, and more also, if ought but death part thee and me.”

Here, we have what is (in my opinion) one of the most moving passages in Scripture, which has become one of my favorites.

First, purely to get it out of the way: Yes, there do exist queer readings of Ruth that, at the very least, sound like they’re in Officially Making It Weird territory. I am not doing that; I feel no need to comment further on this, nor to act as though queer people in general are answerable for such readings. This is for the same reason that I neither asked nor expected straight people in general to be answerable for that weirdo from a couple months back7 with the Sumerian avatar who wrote a twenty-tweet thread “proving” that incest is a great breeding strategy, while also assuring everybody that he “wasn’t being a pervert about it,” and that he was in a “same-race relationship” (which was definitely my first question): Even if that guy were statistically representative of heterosexuals, which I am glad to concede he is not, it would still not be heterosexuality’s fault that he’s a creep—it would be, and is, his own.

Anyway, let’s return to our text, shall we?

The setup of the book is that Naomi, with her husband Elimelech and her two sons, went to Moab during a famine, because there was food in Moab and not in Judah. The boys, Mahlon and Kilion, lived long enough to marry, although it’s worth noting that their names (מַחְלוֹן [Maḥlawn] and כִּלְיוֹן [Kilyawn]) mean “sickness” and “wasting,” suggesting they were plagued by ill-health from the start. In any case, both they and Elimelech died—and then, Naomi heard that the famine in Judah had let up, so she resolved to return home.

Ruth and Naomi (1795), by William Blake.

Now, Ruth and Orpah’s relationship to Naomi is striking. It may actually be unique? I can’t think of any other well-known friendships of mothers-in-law with daughters-in-law in the Bible. Or outside of it, actually—it’s not a link that has fired the artistic imagination much, as far as I can tell. They have affinity, or kinship by marriage (as contrasted with consanguinity, or kinship by descent from a common ancestor). But every concrete emblem of that is now gone: all are widowed; all are childless. Furthermore, Naomi is past all prospect of remarriage—her hypothetical about levirate marriage is clearly sarcastic. Even re-establishing the link they previously had is completely implausible.

It would be understandable for this elderly woman to beg her daughters-in-law to stay with her. We’re talking about the early Iron Age, when familial ties, even by affinity, were far more sacred, and when being a childless widow as almost the worst hand life could deal you. (There was an even worse one, which was being a foreign childless widow in whatever community you happened to be; ha, can you imagine.) Three is a much safer number than one is such circumstances, safer even than two. But Naomi doesn’t do that. She looks at these young women, who still have most of the charms of virginity and almost none of the disadvantages of second-marriage seekers; they’ve got a very good chance in Moab. She can’t do this to them. She tells them to go home.

And poor Orpah must have been so relieved to get that second chance!

Can you imagine the terror, the discomfort, the dreariness, the indignity, of moving to a foreign country with your mother-in-law and sister-in-law, all for the opportunity to live off the charity of strangers? And yet she was going to do it! Until the moment, like water in the desert, when Naomi’s familiar voice sounds in her ear: “It’s alright, Orpah. Go home.”

But not Ruth. Oh, no. To quote Firefly, this woman was my kind of stupid.

Bethlehem (1882), by Vasily Polenov.

I’m sure her common sense told her Orpah was doing not just the excusable thing, but the smart thing. (Possibly even the courteous thing, by accepting an immensely generous gift.) Then Ruth’s mind turns to Naomi’s own prospects; and she realizes that Naomi’s plan is probably, in its entirety, Go back to Bethlehem and wait to die.

And Ruth’s response is “Absolutely not, the hell with that—I swear to your God I will not let you die like that, Naomi.” And that was that; and thus did Ruth become a foremother of Jesus.

A lot of people read this as a “chosen family” type of story, which in turn forms a natural source for application of the text to LGBT people. A major element in queer culture is the fact that, especially from the 1950s to the 1990s, queer people have often had to forge new, chosen families due to being disowned. Maybe it was for our sexuality or gender identity in themselves; maybe, as of the late ’70s and ’80s, it was after getting diagnosed with GRID (though fairly early on, when they realized straights could get it too, they had to change the name from “gay-related” to “auto-” immune deficiency, and put a “syndrome” on the end for luck). That’s plainly there in the text—doesn’t take any digging to find; it’s a literal description of the action.

That said, I want to highlight something else here, something I rarely hear talked about. In my (quite limited) reading on Ruth, when I’ve seen queer writers tackle it, they’ve focused on the choosing—made it almost a celebration of liberty and autonomy. I’m not aiming to devalue those things, but I don’t think they’re exactly what Ruth 1 is about.

See, the thing about family is that un-chosen-ness is its salient quality. Our first encounter with our own family is totally involuntary. You just wake up in one—and all these affections and duties apparently apply to you that you never agreed to and can’t opt out of. At most, family members can disown each other, but even that doesn’t actually make them stop being related; it just makes them traitors.

The Outcast (1851), by Richard Redgrave,

depicting a father expelling his daughter

and her illegitimate baby.

You might be thinking, “Hang on, though—the family is the fruit of marriage, and marriage is chosen. Which, hey, isn’t all family chosen in that sense?” You are correct. But what is marriage?

Marriage forges bonds of kinship that nature did not of itself impose. It takes a willingly-chosen bond, and says of that bond, “I assent to this being woven into me in such a way that I am no longer able to withdraw from it.” That’s why effecting it requires both mutual vows before witnesses (the social, public, and ritual aspects of kinship) and also bodily union (kinship’s personal, animal, and mystical dimensions); it’s why marriage is indissoluble, and why we specifically need to invoke our Maker when we make these vows. If we want to stitch something into ourselves as irrevocably as that, we need our intent to be ratified by, or at the least self-consciously witnessed to, the Absolute.

You may now be thinking, “Fine; what has this got to do with Ruth 1? Ruth marries Boaz; you promised you weren’t making it weird, man.” She does, and I’m not! But look again at the vow Ruth swears to Naomi. It invokes the Lord, and to punish (“the Lord do so to me”), and does so open-endedly (“and more also”)—that’s about as bold as vows get! But the point this exemplifies is that marriage is not the only kind of chosen kinship that can, or does, or should exist among the Lord’s people. Marriage is uniquely sacramental. But are we aware of the “brothers and sisters and children and mothers” we could have if we looked? As Grant Hartley has pointed out, this is something the LGBT community is in a position to help the Church in this country understand.

Footnotes

1The name Euodia (or Euodias)—which would be better adapted to English, a less vocalic language than Greek, as Evodia—means “fair song,” while Syntyche means “fortunate, lucky” (making it a nearly exact Greek equivalent of the Latin name Felicitas).

2The title was not transferable: Even an earlier miscarriage, regardless of sex, would disqualify an eldest son from being a legal firstborn. The upshot of this, combined with the much higher infant and child mortality rates of the Iron Age at all periods, is that less than half the households in ancient Israel would have had a firstborn.

3I wasn’t able to dig up any info about the most commonplace Aramaic term for “soul”; Aramaic is closely related to Hebrew, and like it also has a two- rather than a three-gender system, so if I had to guess, I’d bet on the Aramaic word being feminine. On the other hand, the other common terms in Latin and Greek that are rendered “spirit” are spiritus and πνεῦμα [pneuma], which are masculine and neuter respectively. (The Anglo-Saxon ᚷᚪᛋᛏ [gāst], from which we get the Modern English “ghost” though it originally referred to spirits in general, was also masculine.)

4Or, from another perspective, since St. John of the Cross was a Carmelite: its very finest.

5Dante’s guardian after his father’s early death was a man named Brunetto Latini, to whom he pays moving tribute in the Inferno, wherein he meets Latini among those punished for sodomy. Dunstan Thompson, whose work is sadly neglected today, was an American poet who settled in England with his lover, Philip Trower, following the war; not long thereafter, he reverted to the Catholic faith he had been raised in, and Trower converted, the two choosing (with their bishop’s approval) to live “as brothers” rather than separate.

6The word paganus, the root of “pagan,” has a couple of meanings in Latin. One is “country (folk), rustic,” as contrasted with city-dwellers. Since Christianity first spread chiefly through cities, this is often assumed to be why “pagan” now means what it does. However, paganus could also mean “civilian (as contrasted with military),” and, in light of the war imagery found in St. Paul and the Apocalypse, I’m intrigued by the idea that this may be a contributing or even controlling factor.

7As mentioned in Chapter One, this was originally composed last June. As for the Twitter account I’m alluding to, I don’t recall the handle, and don’t feel I’m missing anything crucial in life due to that defect of memory.

8Affinity is thus contrasted with consanguinity, or kinship by descent from a common ancestor.