Follow these links for Part I and Part II.

Also: All of my content has always been free to read since I began this blog; however, in case you hadn’t come across it and would like to support me, I have a Patreon. I mention it because I’m coming up to a fairly serious financial pinch in about three weeks—if you’d be willing to sponsor me, even temporarily, that’d be really great. Thank you.

בֵּית־הַמִּקְדָּשׁ [Bêyth ha-Miqdâsh]1

So. We got our arrangement of the Old Testament—law, history, poetry, prophecy, and (sometimes) I and II Maccabees stuck on the end there, or LHPPASIAIIM for short2—from the Septuagint, but the arrangement of the Hebrew Bible, a.k.a. the Tanakh, is rather different and more focused. The number and ordering of its books is theologically significant, in part because it is liturgically significant; and the Israelites exist as a people for the sake of worship. This is why the Tabernacle, so minutely described in the latter half of Exodus, was central. We’ve explored all this primarily in the context of ten books: the five books of the Law (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) and the “Five Scrolls” dedicated to particular holy days (Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, and Esther).

We now turn to the two sets of four (the Former and Latter Prophets) and the two sets of three (the “Books of Truth” and the rest of the Kethuvim).

Archæological site of Shiloh (modern Khirbet

Seilun, West Bank), where the Tabernacle was

set up before David’s time. Photo by Deror

Avi, used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

Over the course of the Prophetic books, we see two major alterations in the activity of the Presence that met the Hebrews in the Torah. Both changes are described first in the historical idiom of the Former Prophets, and then again in the poetic idiom of the Latter Prophets. The first change, which takes place several centuries after Canaan has been conquered (Joshua) and dwelt in for some time (Judges)—during which the Presence is housed chiefly at Shiloh in the territory of the tribe of Ephraim (Samuel)—is that It consents to be re-housed, dwelling in Solomon’s Temple instead (Kings).

The significance of this change is much greater than we habitually realize: Temple and Tabernacle alike are foreign to us. It’s worth dwelling on it a little, to try and get the magnitude of this transition into the mind. The key thing to remember about the Tabernacle is, it was a tent. By design, a tent is a temporary dwelling. Between the Exodus and the death of Moses, the Israelites were not only pastoral—which they remained even after settling in the Holy Land—but nomadic. The Tabernacle therefore needed to be portable. Its holiness was guarded with extreme care, as can be observed in the fourth chapter of Numbers, where clear instructions are given for how the various parts of the Tabernacle are to be carried, how they to be wrapped up before carrying, who is to do the wrapping up, who is to do the carrying (not the same people who do the wrapping up), and even when the carriers are allowed to come in and fetch things. Shielding the holy vessels from the touch or sight of anyone not authorized to lay hands or eyes on them—or rather, shielding the vast majority of people from the risk of committing that touch or sight (a care, we may remember, not taken on one occasion when the Ark was moved, which did result in a death)—was a thoroughly practical traveling concern, because it was all frequently on the go.

Willow Peak (with St. Catherine’s Monastery in

the foreground), held by some Christians to be

Mount Horeb. Photo by Esben Stenfeldt,

used under a CC BY 3.0 license (source).

This goes along with a set of images that recurs in both the Old and New Testaments: that of God’s elect as a people without a home: now guests, now captives, now refugees, now pilgrims. The Epistle to the Hebrews gives beautiful expression to this image, while at the same time forming a bridge to the contrasting image of the city.

These all died in faith, not having received the promises, but having seen them afar off, and were persuaded of them, and embraced them, and confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on the earth. For they that say such things declare plainly that they seek a country. And truly, if they had been mindful of that country from whence they came out, they might have had opportunity to have returned. But now they desire a better country, that is, an heavenly: wherefore God is not ashamed to be called their God: for he hath prepared for them a city.

—Hebrews 11:13-16

David welcoming the Ark of the Covenant into

Jerusalem (II Samuel 6), part of a folio from

the Morgan Bible (13th c.), likely Parisian.

The Tabernacle was the sanctuary of a pilgrim deity, an encampment that might last many a year but, it was implied, would be heading elsewhere at some point. Which it did, even after the Holy Land was conquered; the Ark that abode in Shiloh while Samuel judged the Hebrews was there no longer by the time Solomon was king.

A temple, though? That is a house. Literally! The normal Hebrew term for the Temple is the בֵּית־הַמִּקְדָּשׁ, “the Holy House.” (This same element beyth or beth is present in the names of many cities, like Bethlehem.) A structure with walls instead of curtains implies permanence, residence here and not there, fixity. The transition from the Tabernacle to the Temple is thus a dramatic statement about how that Presence proposes to dwell with Israel; it is, also, a statement about the House of David whom he suffered to build him this house, which he had at first refused (and, covertly, about the House he promised to build David when the latter raised the question of building the Lord his God a house).

The glory that now settles on the Israelites, and supremely upon Jerusalem, compares with nothing else in the Tanakh. As described by Gary Anderson in his recent book That I May Dwell Among Them, here and there in the Hebrew Bible, the holy city becomes almost an extension of the Lord himself, as the furnishings of the Tabernacle were already. Glorious things of thee are spoken, Zion, city of our God … Round each habitation hov’ring, see the cloud and fire appear / For a glory and a cov’ring, showing that the Lord is near …

Sīc Trānsit Glōria Cælōrum3

In this light, the second change the prophets record is unutterably catastrophic. God abandons the Temple.

This is suggested in Jeremiah 39-41, which recounts the siege of city and its fall to the Babylonians. It becomes explicit in a vision in Ezekiel 8-11; indeed, it is there recorded in agonized detail. The episode begins with a description of the idolatrous filth with which the whole Temple complex is secretly riddled, creeping through the very walls of the place like rats; it ends with the majestic, terrible, enigmatic shapes of the ophanim (emblems of the divine Presence)4 rising away from Jerusalem and crossing eastward over the Kidron Valley, before Nebuchadnezzar approached the city.

Jeremiah on the Ruins of Jerusalem

(1844), by Horace Vernet.

This desolation does not come out of nowhere. There have been many warnings, many acts of more limited discipline. There have even been some good periods and times of repentance. Isaiah records some of these ups and downs, as do the first four of the Twelve Prophets. (Modern scholars debate both when these prophets lived and when the books bearing their names were composed, but remember, what we are aiming to illuminate is the significance of how the Tanakh is arranged. For that purpose, what’s more relevant is the traditional understanding that these five prophets prophesied during the heyday of Solomon’s Temple.)

Yet with time, the repentance never lasts; nothing but the extreme solution will do. God withdraws himself from the Temple, which is destroyed. Those early chapters of Ezekiel aren’t merely tragic. There is something sickening in them. And it isn’t due to the grime and muck and insects which the clergy, government, and academics of the realm are discovered dabbling in, either; these easily excite disgust, but a normal sort of disgust. The truly sublime horror comes when, as the prophet watches, the שְׁכִינָה [Sh’khynâh], the luminous Presence, lifts itself off the Mercy Seat that surmount the Ark of the Covenant, passes the threshold of the Temple, and deserts the holy city, settling for a time upon Mount Olivet, and finally vanishing—like the Ark itself.

Nevertheless—impossibly, though Israel’s literal raison d’être has deserted the place where he set his Name—the narrative continues to move forward. Ezekiel hints at this, with a vision of a new Temple, a new holy city, a new allotment of the land to a restored Israel, all twelve tribes once again present and accounted for. The last triad of the Minor Prophets (Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi) actually witness the fulfillment of this vision: The days of their prophecy are those when the foundations of the Second Temple are laid and its walls begin to rise.

Proroctwo Ezechiela [The Prophet Ezekiel] (1919), by Jacek Malczewski.

The Book of Dad Jokes

So the two sets of five and the two sets of four have been dealt with—like four walls forming a perimeter around the Temple, their center. There remain only the two sets of three: Psalms, Proverbs, and Job, and Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah, and Chronicles. While Proverbs and Job supply little more than quotations here and there in the Judaic liturgy, they have their role, and (like the Megilloth) it is a ritual role. The final three books, on the other hand, are slightly curious inclusions, with little to no liturgical importance to the synagogue.

As far as I was able to find out, they have no collective name. Their initials in Hebrew, דעד [d-‘-d],5 don’t appear to form a radical. However, since the middle letter ayin starts with an a in English, and all three display some concern with Jewish lineage, we likely shouldn’t call these “the Books of DAD,” and—now that I’ve put the idea in your head—we are 100% going to.

Now. I said that there’s a sense in which these three volumes are the key to the rest of the Tanakh. This is because even these books, which see little to no liturgical use, share the same focus that was present in both sets of five, both sets of four, and the previous set of three. It’s the Temple. It always comes back to that; that is the beating heart of the Tanakh.

The Holyland model of the Second Temple. Photo

by Wikimedia contributor Ariely, used under

a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

This focus is at its most obvious in Ezra-Nehemiah, which is of course entirely about the building of the Second Temple; its presence in Daniel and Chronicles may be less obvious. But consider the following from the former:

Seventy weeks are determined upon thy people and upon thy holy city, to finish the transgression, and to make an end of sins, and to make reconciliation for iniquity … [F]rom the going forth of the commandment to restore and to build Jerusalem unto the Messiah the Prince shall be seven weeks, and threescore and two weeks: the street shall be built again, and the wall, even in troublous times. And after threescore and two weeks shall Messiah be cut off … and the people of the prince that shall come shall destroy the city and the sanctuary … And he shall confirm the covenant with many for one week: and in the midst of the week he shall cause the sacrifice and the oblation to cease, and for the overspreading of abominations he shall make it desolate, even until the consummation …

—Daniel 9:24-27

This is a weird thing to say in a post about understanding Scripture, but, don’t worry about the interpretation right now! Instead, think about its historical context.

The Historical Context of the Books of DAD

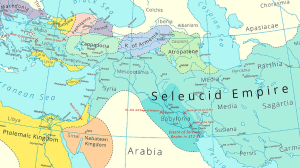

Part of a map of the Near East and adjacent

regions ca. 200 BC, by Wikipedia contributor

Avantiputra7, used under a CC BY-SA 4.0

license (source).

Though Christians have habitually placed Daniel in the section with the other in-our-sense-prophets, this is not the approach to Daniel taken either by traditional Judaism or modern scholarship. As for the scholars, they see in Daniel (one of the only two books in the Tanakh written partly in Aramaic) a product not of the sixth century BC, but of the second.

This was the period during which the Seleucid Empire—the largest successor state of the conquests of Alexander the Great—attempted to exterminate Judaism, and in doing so provoked the celebrated Maccabee Revolt. The “people of the prince” who will “cause the sacrifice and the oblation to cease” due to “the overspreading of abominations” are references to Antiochus Epiphanes, who (besides having an excellently-chosen villain name) was the Seleucid Emperor from 175 to 164 BC. Among other unlovely choices, Antiochus rededicated the Temple in Jerusalem to Zeus, and had a pig offered on the altar. Daniel’s references in ch. 11 to the “king of the north” are likewise thought to be coded references to the Seleucids. This kind of coding allowed political and spiritual resistance to be maintained and spread under highly adverse conditions, via symbols known to the oppressed but not easily guessable by the oppressor. Most of Daniel’s oracular content (chapters 7-12, most of the back half of the book) is apocalyptic of this sort; note, too, how in the more “folk tale” style opening chapters, significant emphasis is laid not only on the fact that Daniel and the young Judahites who follow his lead not only refuse to worship idols, but circumspectly avoid all meat that may be served to them, thus ridding themselves of the risks of eating either meat which may have been sacrificed to idols or treyf (non-kosher meat) that may have been disguised as something ritually permissible to Jews—topical concerns during the second century BC.

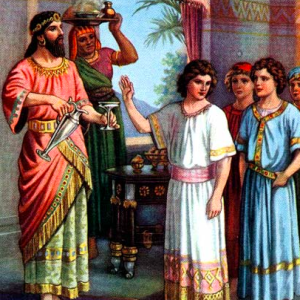

An illustration (ca. 1900) for the Book of

Daniel by Otto A. Stemler—to my mind, a

bizarrely chill take. “Hey kids, want some

ritually impure foods?” “Nah.” “Okay, fair.”

Likewise, Chronicles makes the Temple central. The Book of Kings bounces back and forth between the Israelite and Judahite monarchies; Chronicles concerns itself only with the affairs of Judah, the home of the Temple of Solomon, whose construction and dedication it records—they’re right in the middle of the book, in fact. According to our reference system, they take up six chapters (II Chronicles 2-7) in a sixty-five chapter book. Moreover, this is the last book in the Tanakh, and its closing verses are as follows:

All the chief of the priests, and the people, transgressed very much after all the abominations of the heathen; and polluted the house of the Lord which he had hallowed in Jerusalem … until the wrath of the Lord arose against his people, till there was no remedy. Therefore he brought upon them the king of the Chaldees, who slew their young men with the sword in the house of their sanctuary … And all the vessels of the house of God, great and small, and the treasures of the house of the Lord … all these he brought to Babylon. And they burnt the house of God, and brake down the wall of Jerusalem … to fulfill the word of the Lord by the mouth of Jeremiah, until the land had enjoyed her sabbaths: for as long as she lay desolate she kept sabbath, to fulfill threescore and ten years.

Now in the first year of Cyrus king of Persia, … the Lord stirred up the spirit of Cyrus … that he made a proclamation throughout all his kingdom, … “Thus saith Cyrus king of Persia, All the kingdoms of the earth hath the Lord God of heaven given me; and he hath charged me to build him an house in Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Who is there among you of all his people? The Lord his God be with him, and let him go up.”

—II Chronicles 36:14-23

In short, the Tanakh’s arrangement—unlike the Septuagint’s—is the very opposite of unsystematic. It is carefully honed to make a theological point: The Temple is the heart of Israel, and the Lord sits enthroned in the heart of the Temple.

For Christians, this prompts two questions, of very unequal importance. First, where do the Deuterocanonicals fit into this schema, if at all? And second—what are its implications for the New Testament?

Footnotes

1This is the Hebrew name for the Temple, and is typically translated “the Temple” or “the holy temple” in English (the radical q-d-sh “holy, sacred,” which appears in miqdash, also underlies place names like Kadesh that may originally have been or contained shrines). However, a more literal rendering of beyt ha-miqdash is “the holy house,” and “house” is usually the term in the original language, in both Testaments of the Christian Bible (בֵּית in Hebrew, οἶκος in Greek), when our Bibles say “temple.”

2Oh, this will catch on. That’ll show you.

3This phrase means “thus passeth the glory of the heavens”—a pun on the maxim Sīc trānsit glōria mundī, “thus passeth the glory of the world.” (From the early fifteenth century to the mid-twentieth, the traditional phrase was an element in the coronation ritual of the popes.)

4Exactly what the ophanim are is not absolutely clear. They appear only in Ezekiel. They are usually identified as the choir called the Thrones; however, they are accompanied by tetramorphs (the beings described as having the four faces of an ox, a lion, an eagle, and a man), who are usually interpreted as Cherubim rather than Thrones, and it’s not plain whether the ophanim and the tetramorphs are two distinct creatures that always move together, or a single creature with multiple simultaneous organs, or manifestations, or something of that kind.

5My usual system of transliteration would use ṛ here instead of ‘, but, and this is important, if I did it that way the joke wouldn’t work as well.