This post is part of a series.

Part I: The Septuagint and the Masoretic Text

Part II: The Outline of the Hebrew Bible

Part III: The Biblical Centrality of the Temple

⇒ Part IV: The Blueprint of the New Testament

Also: All of my content has always been free to read since I began this blog; however, in case you hadn’t come across it and would like to support me, I have a Patreon. I mention it because I’m coming up to a fairly serious financial pinch in about two weeks—if you’d be willing to sponsor me, even temporarily, that’d be really great. Thank you.

The Deuterocanon

Note: This post has a larger number of Biblical quotations than usual; I’ve placed them in small font to save a little space. As a rule, only the gist of them is necessary to follow the argument anyway.

Title page of Thomas Cranmer’s 1552 Boke of

Common Prayer, and Administration of

the Sacramentes.1

As you may have guessed, I quite like the templar focus which the arrangement of the Tanakh involves. I’d like to see it restored in Christian Bibles and, in a sense, extended. I believe a version of this can animate—even, maybe, originally led to—the structure of the New Testament.

But we’ll get to that. Picking up from the end of Part III, the first question—where to fit the Deuterocanon (the books most Protestants call “the Apocrypha”) into the Old Testament2—is actually fairly straightforward; most of it can simply be inserted after Chronicles, though I’d urge the additions to Esther and Daniel to be put where they properly occur in the narrative. There are two minor changes below that will be æsthetically important later, but do not affect the content of the books in question.

THE LAW

I. Genesis

II. Exodus

III. Leviticus

IV. Numbers

V. Deuteronomy

THE FORMER PROPHETS…….THE LATTER PROPHETS

VI. Joshua…………………………………..X. Isaiah

VII. Judges………………………………….XI. Jeremiah

VIII. Samuel…………………………………XII. Ezekiel

IX. Kings……………………………………..XIII. The Twelve

THE FORMER WRITINGS

XIV. Psalms…………………………………..XX. Ecclesiastes

XV. Proverbs…………………………………XXI. Esther (with Greek additions)

XVI. Job………………………………………..XXII. Daniel (with Greek additions)

XVII. The Song of Songs……………….XXIII. Ezra

XVIII. Ruth…………………………………….XXIV. Nehemiah3

XIX. Lamentations…………………………XXV. Chronicles

THE LATTER WRITINGS (A.K.A. THE DEUTEROCANON)

XXVI. Tobit……………………………………..XXX. Sirach

XXVII. Judith4…………………………………XXXI. Wisdom

XXVIII. Baruch………………………………..XXXII. I Macabees

XXIX. Letter of Jeremiah3……………….XXXIII. II Maccabees

This nets us an Old Testament of thirty-three books: the twenty-four of the Tanakh, raised to twenty-five by distinguishing Ezra and Nehemiah, plus the eight Deuterocanonical books (normally counted as seven, since the Letter of Jeremiah is treated as the sixth chapter of Baruch). The segment called Kethuvim in Hebrew Bibles, now “the Former Writings,” has been a bit spoilt from its original structure, its 3-5-3 symmetry upset by re-splitting Nehemiah; on the other hand, “the Latter Writings” imitate the prophets both in their name and in their number (eight).

Judith With the Head of Holofernes (1613),

by Cristofano Allori—who I think gives her

major Sarah Paulson energy, right? Am I

crazy? Are you seeing this? Amanda!

Link to Link

Incidentally, I think it’s worthwhile to arrange the Deuterocanonicals this way specifically. Thus ordered, we have four books set early in the “intertestamental” period of Jewish history—Tobit and Judith are morality tales about the recompense of faithfulness, while Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah warn against idolatry; Tobit, Baruch, and the Letter all profess to be from within a few decades of the Temple’s destruction. These are succeeded by another four, written from the early second century BC to, perhaps, as late as the mid-first century CE: Sirach is thought to have been composed not too long before the Maccabean Revolt (the main phase of which took place in 167-160 BC), while some scholars date the composition of the Wisdom of Solomon as late as the reign of Caligula (37-41 CE), though the mid-to-late first century BC is more common.

What’s key here is concluding with the books of the Maccabees. This does two things, one of which is to lend the Deuterocanonicals themselves a nice full-circle effect. They open with the narrator of Tobit explaining that he was one of the few faithful Israelites of the northern kingdom who duly offered sacrifices at Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem, until he and his family, like so many other Israelites, were carried off by the Assyrians to settlements east of the Tigris. They close with the faithful few in Judea successfully reclaiming, cleansing, and reconsecrating the Second Temple (the origin of Chanukkah). This full circle in turn locks into the structural message of the Tanakh: the central importance of the Temple, and the vocation of the people of Israel—whatever remnant may be left—to maintain it.

Wills and Testaments

So let’s turn to the harder question. If the Old Testament is all about the Temple, in what way does that shed light on the New?

The word testament is, obviously, English, descended from the Latin testamentum. When it appears in our Bibles, it generally translates either the Hebrew בְּרִית [bryth] (as in brit milah, or bris in Yiddish, i.e. a circumcision) or the Greek διαθήκη [diathēkē]. Both words are better rendered “covenant,” and it is in reference to this that the two Testaments of the Bible are so named. The New Covenant is the one instituted through the mediation of Jesus, as the Old was instituted through the mediation of Moses.

It is probably worth pausing here to note that “covenant” is not a word we understand particularly well these days, because covenants are no longer things of everyday life. Usually, “covenant” is merely a fancy synonym for “contract” in modern English, and reading this meaning into Scripture seems to be reinforced by the fact that covenants, like contracts, involve obligations that usually have a legal character (and are virtually always thought of and spoken about in legal-ese, whether the law is actually going to enforce them or not). Even etymologically, the term descends from a Latin word for “agreement,” and is related to, of all things, the word “convenient”!

But of course if “agreement” or even “legal agreement” were all covenant meant, we need hardly have borrowed a term when we had native words that would serve that purpose.5 In the Ancient Near East, where the roots of Judaism and Christianity lie, a covenant was something more than a contract; the very lives of those who covenanted with one another were bound into the obligations they undertook; it thus created not just duties (as all promises do), but kinship. The suzerain-vassal treaty of the Ancient Near East is prototypical: In covenants of this type, the suzerain vows to protect and provide for the vassal for obedience and to punish the vassal for disobedience, while the vassal on their part vows to obey the suzerain; the covenant is sealed by the pair walking together between a series of animals that have been cut or torn in half, symbolizing both parties calling the animals’ fate down upon themselves if they should break their word. (It is accordingly shocking that, when God calls upon Abram to prepare animals for this kind of covenant in Genesis 15, Abram himself does not pass between the animals, but two theophanies do so: In other words, God calls upon himself alone all vengeance for either party’s breach of the covenant.)

Correspondingly, a new covenant calls for a new law. This is contained in the teaching of Jesus—supremely, in the Upper Room Discourse of John 13:31-17:26, where he explicitly tells the Eleven (Judas has left already) that he is giving them “a new commandment.” The Gospels and Acts, taken together, make five books: The Old Covenant had its Pentateuch, and the New has its Pentateuch.

Genesis…Exodus…Leviticus…Numbers…Deuteronomy

Matthew….Mark……..Luke……….John………….Acts………..

Made Without Hands

Now, in this collection of books, there are several interesting statements about the Temple. Consider the following:

The woman saith unto him, “Sir, I perceive that thou art a prophet. Our fathers worshipped in this mountain; and ye say, that in Jerusalem is the place where men ought to worship.”

Jesus saith unto her, “Woman, believe me, the hour cometh, when ye shall neither in this mountain, nor yet at Jerusalem, worship the Father. Ye worship ye know not what: we know what we worship: for salvation is of the Jews. But the hour cometh, and now is, when the true worshippers shall worship the Father in spirit and in truth: for the Father seeketh such to worship him.”

—John 4:19-23

Then answered the Jews and said unto him, “What sign shewest thou unto us, seeing that thou doest these things?”

Jesus answered and said unto them, “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up.”

Then said the Jews, “Forty and six years was this temple in building, and wilt thou rear it up in three days?” But he spake of the temple of his body.

—John 2:18-21

And the chief priests and all the council sought for witness against Jesus to put him to death; and found none. For many bare false witness against him, but their witness agreed not together. And there arose certain, and bare false witness against him, saying, “We heard him say, I will destroy this temple that is made with hands, and within three days I will build another made without hands.” But neither so did their witness agree together.

—Mark 14:55-59

Ikon of Christ Pantokrator (6th c.) from St.

Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai,

Egypt. One of the oldest surviving Christian

ikons in the world.

The same sort of remarks, in a slightly different vein, continue in the collection of letters that profess to be composed by the designated “emissaries” or “envoys” of the messianic claimant of the Gospels—writings which would on such grounds stand in a similar relation to the Gospels that the Nevi’im do to the Torah. That list of letters runs as follows (the first fourteen are named for the congregations or persons to whom they were addressed—all fourteen were long held to be by the same individual, Paul, and all except the fourteenth profess to be by Paul—while the remaining seven are named for their putative authors):

Romans—I Corinthians—II Corinthians—Galatians—Ephesians—Philippians—Colossians—I Thessalonians—II Thessalonians—I Timothy—II Timothy—Titus—Philemon—Hebrews—James—I Peter—II Peter—I John—II John—III John—Jude

Here follow a couple of samples of the sort of remarks they make. The difference in vein is that, while affirming in some places that the “body of Christ” was a literal, physical entity born of a woman, they also seem in some sense to identify it with the metaphorical “body of people” who accept his halakhic and prophetic authority:

The Lord is gracious. To whom coming, as unto a living stone, disallowed indeed of men, but chosen of God, and precious, ye also, as lively stones, are built up a spiritual house, an holy priesthood, to offer up spiritual sacrifices, acceptable to God by Jesus Christ. Wherefore also it is contained in the scripture, “Behold, I lay in Sion a chief corner stone, elect, precious: and he that believeth on him shall not be confounded.” Unto you therefore which believe he is precious: but unto them which be disobedient, “the stone which the builders disallowed, the same is made the head of the corner,” and “a stone of stumbling, and a rock of offense,” even to them which stumble at the word, being disobedient: whereunto also they were appointed. But ye are a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, an holy nation, a peculiar people.

—I Peter 2:3b-9a

Now therefore ye are no more strangers and foreigners, but fellow-citizens with the saints, and of the household of God; and are built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Jesus Christ himself being the chief corner stone; in whom all the building fitly framed together groweth unto an holy temple in the Lord: in whom ye also are builded together for an habitation of God through the Spirit.

—Ephesians 2:19-22

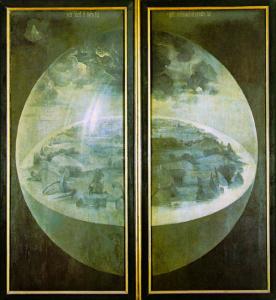

French tapestry depicting the New Jerusalem

(14th c.); photo by Wikimedia contributor

Octave 444, used under a CC BY-SA 4.0

license (source).

The last text included in the canon of the New Testament titles itself in its opening verse as The Apocalypse of Jesus Christ (though it is more widely known as of John, its self-identified author). Like the only major apocalypse of the Old Testament, Daniel, it is placed after the expository commentary that makes up the second section of the collection of canonical material; and since it is the only apocalypse accepted by the Church as inspired, it therefore forms a section unto itself. Like the three final books of the Kethuvim, it also takes up the motif of the Temple; indeed, it is richer with templar imagery than any other book of the New Testament—with perhaps one exception.

And another angel came and stood at the altar, having a golden censer; and there was given unto him much incense, that he should offer it with the prayers of all saints upon the golden altar which was before the throne. And the smoke of the incense, which came with the prayers of the saints, ascended up before God out of the angel’s hand. And the angel took the censer, and filled it with fire of the altar, and cast it into the earth: and there were voices, and thunderings, and lightnings, and an earthquake.

—Revelation 8:3-5

And the temple of God was opened in heaven, and there was seen in his temple the ark of his testament: and there were lightnings, and voices, and thunderings, and an earthquake, and great hail.

—Revelation 11:19

And I John saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a great voice out of heaven saying, Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men, and he will dwell with them, and they shall be his people, and God himself shall be with them, and be their God. … And had a wall great and high, and had twelve gates, and at the gates twelve angels, and names written thereon, which are the names of the twelve tribes of the children of Israel … And the wall of the city had twelve foundations, and in them the names of the twelve apostles of the Lamb. … And I saw no temple therein: for the Lord God Almighty and the Lamb are the temple of it. And the city had no need of the sun, neither of the moon, to shine in it: for the glory of God did lighten it, and the Lamb is the light thereof.

—Revelation 21:2-3, 12, 14, 22-23

The single book that may rival Revelation for its interest in the Temple is also the single book of the New Testament that is thoroughly anonymous. The Gospels have had their attributed authors (correctly or not) as far back as we know the books themselves; all the other epistles and the Apocalypse are signed, even if it be with no more than “the elder.” Only Hebrews is without author, without amanuensis, having neither epistolary preface nor the “large letters I write with my own hand” that St. Paul used to assure his readers of the authenticity of his writings. And only there, in a passage that almost reads like preparation for an Apocalypse that will give more particulars, do we read such stuff as this:

For there was a tabernacle made; the first, wherein was the candlestick, and the table, and the shewbread; which is called the sanctuary. And after the second veil, the tabernacle which is called the Holiest of all; which had the golden censer, and the ark of the covenant overlaid round about with gold, wherein was the golden pot that had manna, and Aaron’s rod that budded, and the tables of the covenant; and over it the cherubims of glory shadowing the mercy-seat; of which we cannot now speak particularly.

—Hebrews 9:2-5

The New Testament, like the Old, is about the Temple; but, as Hebrews states that the priests in Jerusalem “serve unto the example and shadow of heavenly things”—following the doctrine of the Merkavah mystics and the Hekaloth literature that there was a real, transcendent palace in the realms above of which the Temple was a mere copy—it is about the “heavenly things” themselves. And it professes that the Church is one of those heavenly things. Charles Williams, by borrowing the language of the occult and magical schools of Rosicrucianism in which he was trained, gave the feel of the thing perfectly:

The history of Christendom is the history of an operation. It is an operation of the Holy Ghost towards Christ, under the conditions of our humanity …

There had appeared in Palestine, during the government of the Princeps Augustus and his successor Tiberius, a certain being. This being was in the form of a man, a peripatetic teacher, a thaumaturgical orator. … It talked of love in terms of hell, and of hell in terms of perfection. And finally it talked at the top of its piercing voice about itself and its own unequalled importance. It said that it was the best and worst thing that had ever happened or ever could happen to man. … And it promised that when it had disappeared, it would cause some other Power to illumine, confirm, and direct that small group of stupefied and helpless followers whom it deigned, with the sound of the rush of a sublime tenderness, to call its friends.

Pentecost, as depicted (1308)

by Duccio di Buoninsegna.

It did disappear—either by death and burial, as its opponents held, or, as its followers afterwards asserted, by some later and less usual method. … According to their own evidence, the manifestation came. At a particular moment, and by no means secretly, the heavenly Secrets opened upon them, and there was communicated to that group of Jews, in a rush of wind and a dazzle of tongued flames, the secret of the Paraclete in the Church. Our Lord Messias had vanished in his flesh; our Lord the Spirit expressed himself toward the flesh and spirit of the disciples. The Church, itself one of the Secrets, began to be.

—Charles Williams, The Descent of the Dove, Ch. I: The Definition of Christendom

Novum Instrumentum Parte6

In this light, there are two significant changes I would propose we make to the order of the books of the New Testament. There are also a lot of comparatively unimportant changes, which I’d rather like, but which are of little theological importance. (In no case am I supporting that any book be added to or removed from the New Testament.) The revised order I suggest is as follows, with the two books I strongly wish to move underlined:

THE NEW LAW

I. John

II. Matthew

III. Mark

IV. Luke

V. Acts

THE EPISTLES: PETRINE

VI. I Peter

VII. II Peter

VIII. Jude

THE EPISTLES: JACOBEAN

IX. James

THE EPISTLES: JOHANNINE

X. I John

XI. II John

XII. III John

THE EPISTLES: PAULINE

XIII. Romans

XIV. I Corinthians

XV. II Corinthians

XVI. Galatians

XVII. Ephesians

XVIII. Philippians

XIX. Colossians

XX. I Thessalonians

XXI. II Thessalonians

XXII. I Timothy

XXIII. II Timothy

XXIV. Titus

XXV. Philemon

XXVI. Hebrews

THE APOCALYPSE

XXVII. Revelation

The rearrangement of the epistles into four “schools” is based on the honor in which the apostles were held. St. Peter was esteemed the “prince of the apostles”; St. James the Less as the first Bishop of Jerusalem was probably second; John as another intimate of Christ would scarcely have been behind either of them; St. Paul, as the self-proclaimed “least of the apostles,” is in fourth place. (Note that the adjectives here, Petrine, Jacobean, Johannine, and Pauline, are meant to denote schools or styles of thought, not necessarily direct authorship. While I accept more of the traditional New Testament ascriptions than most professional scholars do, I don’t think that II John, III John, or Hebrews were written by SS. John or Paul7—and neither I nor anybody I’ve read or heard of thinks that Jude was actually written by St. Peter! but Jude, which is quite similar in content to the last chapter of II Peter, is clearly from the same “school” as that epistle at the very least.8) However, with the sole exception of Hebrews, I consider my proposed rearrangement of the epistles pretty insignificant. The important moves, as indicated, are those of Hebrews to the end of the Epistolary section and of John to the beginning of the New Law.

The reordering of the Gospels has two clear advantages. One is that it places the opening of John where it is obviously intended by its author to be, conceptually—parallel to Genesis, evoking as it does the creation of matter, of light, and of man, all by the Word of God.

Creation (ca. 1490-1510), the outer panels of

Hieronymus Bosch’s famous triptych

The Garden of Earthly Delights.

The other is that, with John moved to the front, Luke and Acts are right next to each other. This allows the Gospel of Luke to flow naturally into the Acts of the Apostles, without the stylistic interruption of the extremely different Johannine pen.

There are other reasons to prefer this arrangement—less pronounced, maybe, but still worth considering, to my mind. With John at the beginning, the New Testament itself gets a nice full-circle effect, beginning and ending with Johannine books. I’d also argue that, as far as theming is concerned, John is the most Temple-focused of the canonical Gospels; he moves the cleansing of the Temple to chapter two, rather than having it up in chapter twelve as it would presumably otherwise be (that being when he recounts the Triumphal Entry), and he notes Jesus visiting the Temple more frequently and on more specific occasions than the Synoptics do—the Synoptics only really describe his going there for the celebration of Passover, whereas John particularly mentions his presence there during Sukkot (7:2-10) and Chanukkah (10:22-23); given the relative unimportance of the latter,9 it sounds as though Jesus may have visited the Temple for every noteworthy festival.

Finally, Hebrews. Moving it to a position right before Revelation again has more than one advantage. Every other epistle in the New Testament professes—truly or falsely—to be by someone in particular, even if “someone” is no more specific than “the elder.” Hebrews alone does not fit this pattern, and in that sense it seems fitting to place it separately from the others; at the end, number twenty-six out of twenty-seven New Testament books, will do nicely.

More significant is its theming: In Hebrews we have another templar book, revolving around the heavenly and earthly tabernacles and the mystery of the Melchizadokite10 priesthood. This not only makes it a good bookend for the prophetic function of the epistles relative to the New Law; it makes Hebrews the perfect bridge between the epistles and the Apocalypse, in which we enter the celestial Temple and stay there for the bulk of the book, or are positioned ambiguously between it and the earth (as the operation of our high priest in Hebrews seems at times to pass between the two or reveal itself in both at once).

And finally, the numbering I recommend, recombining most of the books that were split in the Septuagint, but sustaining the division of Ezra from Nehemiah and newly dividing Baruch from the Letter of Jeremiah—what’s going on with that? Simple: If the books are enumerated that way, we get a thirty-three book Old Testament that, combined with our twenty-seven book New Testament, makes the lovely round number sixty.

So! That’s the long and the short of my harebrained scheme for reorganizing our Bibles completely. And if that idea bothers you, I have good news: I really don’t think any publisher of Bibles is likely to give this a try, or even hear about it. (But I have been toying with making it a guide for myself, in composing Biblical study materials.)

This post is part of a series.

Part I: The Septuagint and the Masoretic Text

Part II: The Outline of the Hebrew Bible

Part III: The Biblical Centrality of the Temple

⇒ Part IV: The Blueprint of the New Testament

Footnotes

1This was the second edition of the Book of Common Prayer (its predecessor had been released in 1549). Further revisions, both doctrinal and ritual, would lead to new editions of the Book in 1559, 1604, and 1662. The 1662 edition remained in use until 1928.

2Though I’ve frequently used “Tanakh” or “Hebrew Bible” up to this point, with the introduction of the Deuterocanonical books, it becomes more strictly accurate to speak of “the Old Testament,” since, while not all Christians recognize these books as inspired, (a) most do, and (b) more significantly, only Christians do, not Jews (with the partial exception of Beta Israel, the Ethiopian Jewish community, who—like, and with, the Ethiopian Christian community—spent some centuries fairly isolated from the rest of their coreligionists). “Apocrypha,” on the other hand, has kind of always been a misnomer. The Greek term literally means “hidden, secret, concealed,” and—I just find it difficult to accept that books which appeared in every Bible for a thousand years and got publicly preached about all over Europe for centuries can be reasonably described as things the Church has kept “secret.” (The term “Deuterocanon” is analogous to “Deuteronomy”: deutero– “second,” canon “rule”—accounts vary as to whether they were so named because their authority was held to be inferior to the rest of Scripture or because their canonicity was established later. If you’re looking for a polite way of indicating these books that neither confirms nor denies their inspiration, “antilegomena” might do, though be aware it usually refers to New Testament writings.)

3In many traditions, these books are combined with the prior entries (making them the latter part of Ezra-Nehemiah and chapter 6 of the book of Baruch).

4Judith is one of an exceedingly tiny number of books we have no readings from in the standard lectionary; if you aren’t familiar with it, it’s kind of good! The plot is essentially “Jael, but make it telenovela.” Given the rich compositional possibilities involved in a story about a beautiful widow decapitating a tyrant, Judith bearing the head of Holofernes was a favorite subject for painters, and occasionally sculptors, during the Renaissance and into the Baroque period (roughly, 1400-1625); following a relative lull, the subject re-emerged in the nineteenth century. Gustav Klimt painted two portraits of Judith, the first of which is particularly celebrated.

5Not that we didn’t do lots of superfluous borrowing from Latin and French when we already had Anglo-Saxon words for things anyway.

6For those people who have the same things wrong with them that I do and therefore would find this funny if they knew the reference, but don’t happen to know it: Erasmus titled his Greek text of the New Testament Novum Instrumentum Omne.

7For Hebrews, I honestly have no theory. Barnabas or Apollos might make sense? though I’d have expected some testimony to the fact from the ancient fathers, if it had been the former. Whoever it may be by, I think it is true that Hebrews bears the marks of someone influenced by St. Paul’s thought, so that it is in that vaguer sense “Pauline.” As for II and III John, I take these to be by John the Elder (a.k.a. “John the Presbyter”), who is mentioned by the church father Papias early in the second century and, according to Eusebius about two centuries later, was a priest at Ephesus who served for a while as the Apostle John’s amanuensis. If so, this would neatly explain the similarities among the whole Johannine corpus (bringing in the Gospel and the Apocalypse as well), since all would be either by St. John himself or a man who worked as his assistant for some years; it also affords a reason for the differences. Revelation might be in such clunky Greek because the Apostle, being in internal exile, had for the first time no choice but to write in that language as best he could, without John the Elder’s aid. Conversely, John the Elder apparently had some reluctance to write at length (a tendency on display in II and III John, but not seriously hinted at in I John and clearly absent from the Gospel of John), while on the other hand not sharing his mentor’s reticence about signing himself directly (“the Elder,” as opposed to the downright painful circumlocution of “This, that, and the other were true about such-and-such an apostle, and that is the one who composed this”).

8John A. T. Robinson makes a case in Redating the New Testament that St. Jude himself might have been St. Peter’s amanuensis for II Peter, thus accounting not only for the similarities between the two letters but a couple of other traits as well, such as the unusual use of Symeon rather than Simon in II Peter 1:1—a discrepancy often smoothed over by translators (Symeon is closer to the original Hebrew/Aramaic form of the name). It would take too long to go into his argument in full, but he proposes that St. Jude wrote his eponymous epistle first and was later engaged by St. Peter to write II Peter. “But he leaves his own signature. For he calls him what he called him—Simeon. The only other person who is recorded as retaining this Hebraic use is his [i.e., Jude’s] brother James (Acts 15.14): it was in the family.” (Robinson, ch. 6, “The Petrine Epistles and Jude,” p. 194 of Wipf and Stock’s 2000 printing.)

9Chanukkah has a pretty outsized importance in the minds of American Gentiles, due to its adoption in some circles as “Jewish Christmas” (a development some Jews have no problem with, while others regard it with immense distaste). Given that the Temple was still standing in Jesus’ day, Chanukkah would probably have enjoyed more status as the feast of its dedication, whereas today it is strictly commemorative. Even back then, however, Chanukkah would presumably have ranked beneath the feasts imposed by the Torah—Pesach (Passover), Matzot (Unleavened Bread, immediately after Pesach and effectively combined with it), Shavuot (Pentecost), Rosh ha-Shanah (the new year), Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), and Sukkot (Tabernacles).

10This is 100% a guess on my part. Of course, Zadokite priests are, or were, a thing, but they were descended from a priest named “Zadok,” with no wonkiness about the vowels; on the other hand, my gut tells me that any adjective derived from the name “Melchizedek” would have to be irregular somehow.