Job 42:7

And it was so, that after the LORD had spoken these words unto Job, the Lord said to Eliphaz the Temanite, “My wrath is kindled against thee, and against thy two friends: for ye have not spoken of me the thing that is right, as my servant Job hath.”

I feel this verse highlights a spiritual issue that seems commonplace in the US at least. It may be common in a lot of places with a substantial and ongoing (or at least fairly recent) history of Christian social dominance.

See, the arc of the book of Job goes like this.

- In chapters 1-2, the book is set up: God brags to Satan, “Hast thou considered my servant Job, that he rules pretty hard?” Satan scoffs and negs God about it, proposing two bets in sequence; both times, God rolls his eyes (yes, this is in the text. Don’t go look) and accepts; Job is then duly, or unduly, immiserated.

- Job’s friends come to comfort him—Eliphaz the Temanite, Bildad the Shuhite, and Zophar the Naamathite (and possibly also Elihu the Buzite, though he may have driven separately)—and the bulk of the book, chapters 3-31, follows. Job lets loose in a lament; Zepp, Bill, and “the Phaz” (as I choose to believe Eliphaz spent three weeks in middle school trying to get his friends to call him) turn out to be Um, Actually people. Job very naturally replies, “Really? Are you really doing this right now? You guys are terrible friends,” to which Zepp, Bill and the Phaz explain, “Um, actually St. Thomas Aquinas defines love as ‘willing the good of the other,’ and we’re trying to help you by correcting your theology, so really we’re being loving? Get it right.”

- Chapters 32-42 form the final and most interesting movement of the book, from which our verse comes. Elihu the aforementioned Buzite gives his “What is even wrong with all four of you?” speech, which proves to be a preface to God’s own speech, the famous “I invented ostriches, what have you punks done lately?” Here Job, the evident victim throughout, very naturally apologizes to God. God then gives Job a new fortune and a fresh set of “replacement” children.

Given its inartistic (and worse, happy) ending, one can see why Job has not remained popular literature. Add to that its painful subject matter, and statistically, you’ve never been invited to a Bible study on the book of Job. But let’s consider our perspective a little bit here. Of the ending in particular, which to some readers feels so cheap, Charles Williams makes the point in He Came Down From Heaven that its implications are rather the opposite; the Stoic solution to the problem of Job, any notion that transitory earthly blessings “don’t really matter,” is clearly rejected.

But we’re focusing on the seventh verse of the last chapter, which is addressed to Eliphaz the Temanite (and can be presumed to include Bildad the Shuhite and Zophar the Naamathite implicitly): “Ye have not spoken of me the thing that is right, as my servant Job hath.”

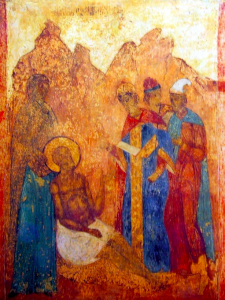

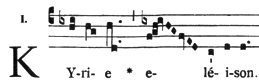

An illustration of Job and his three friends

from the Kyiv Psalter (1397).

Could this “thing that is right” be Job’s stunned acts of contrition in chapters 40 and 42? Maybe; but even if those are in play, I’ve long cherished a hunch that this is about something else. What are the views of the three friends?

- Eliphaz—without (distastefully) resorting to accusations or guesses—chides Job for his angry protestations of innocence; he reminds Job that, before God, no one is spotless; and he urges him to confess any secret sins he may have been harboring.

- I take Bildad to be rather like Mrs. Lynde from Anne of Green Gables. Mostly he takes up Eliphaz’s argument, but helpfully festooned with examples of secret sins Job and/or his ten recently deceased children may have committed. You know, for reference.

- Zophar gives only two speeches, both of which are flowery, Levantine versions of “Hey, how about you just repent already, jerk?” (Notably, of the three, it is Zophar who comes down mostly harshly on Job’s demand that God give him some kind of answer.)

Now. A common thread runs through these three decreasingly-civil modes of engagement. They all begin with this syllogism (∴ means “therefore”):

God is just;

∴ everything that happens is just;

∴ this is happening because, somehow, Job deserves it.

That’s the very thing Job keeps denying. Clearly, he needs to be prompted, almost compelled, to face the only facts that can explain his situa—

YE HAVE NOT SPOKEN OF ME THE THING THAT IS RIGHT,

AS MY SERVANT JOB HATH.

This interpretation is, in my view, strengthened by a verse from Elihu’s abrupt introduction in chapter 32: “Against Job was his wrath kindled, because he justified himself rather than God; also against his three friends was Elihu’s wrath kindled”—why? “because they had found no answer, and yet had condemned Job” (emphasis mine). It is their sense of entitlement to deliver a verdict against their neighbor, and on the basis of things he has suffered (something we now rightly consider appalling), that outrages Elihu.

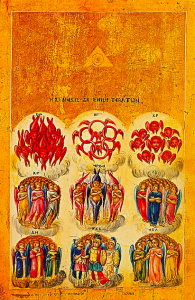

A fresco of Job and his three friends from

the 15th-c. Cathedral of the Annunciation

in Moscow, Russia.

Time would fail, and it would be nothing but a weariness, to recount the ways American churches do all of this to queer people, nonstop. However, I think the promotion of ex-gay and ex-trans “therapies” merits special mention among the tactics of Job’s comforters. We’re talking about techniques and theories that may have merited study when they were first introduced—but they weren’t normal aspects of life under Moses, and they’re not cutting-edge, either. Ex-gay shit has been known not to work since the 1970s. Do not let it cook. Stick a fork in it, it’s done.

Matthew 22:30

In the resurrection they neither marry, nor are given in marriage, but are as the angels of God in heaven.

This is a reminder cishet believers seem to need as much as queer ones at present. Not only will our temporal successes and prestige fall away from us in the end, so will our social bonds and affections; “for we brought nothing into the world, and we can take nothing out of it.” (I think part of the reason US churches have proven vulnerable to fascist sympathizing is a deep failure to accept this fact, long reflected in our unhesitating allegiance to an economic system not merely conscious of, but predicated upon, competitive greed.)

However, what I want to point out is something this verse brings to mind—namely, celibacy, and what a bad job Christians in the US do of supporting it. To be clear, I’m not exempting the Catholic Church from this. Yes, she has a high theoretical view of celibacy, and yes, she affords respected, powerful roles to celibates. But those things aren’t support, especially not at the parochial level. When I was a Protestant, I often saw celibacy treated with hostility, or at least with suspicion, by fellow believers; that attitude is broadly absent from Catholic culture. Nonetheless, if and when it becomes plain that you aren’t entering seminary or the religious life, the average parish (and the average parishioner) seems a bit baffled about what to do with you.

This topic is something of a hobby-horse among Side B people—specifically, among me. However, I firmly deny that this is a “Side B issue,” as it’s sometimes framed. There’s no reason a Side A person couldn’t follow a celibate vocation, just as there’s no reason a heterosexual man couldn’t do so. (This is kind of the point of distinguishing between vocations, which are individual, and morals, which apply to everyone.) Churches that don’t support celibate vocations well in general are hardly going to be better at supporting Side A celibates than Side B ones. I find this disquieting. It’s hard to credit a church with taking the New Testament seriously if they won’t engage with how to do this.

Incidentally, I do also want to explain why this text is extremely funny. In context, it’s part of Jesus’ answer to a riddle posed by the Sadducees, a theological school of Second Temple Judaism, mostly limited to priests. They denied the existence of spirits (both human and angelic), accepted only the Written Torah as Scripture (no other books and no Oral Torah), and did not believe in a general resurrection or a Last Day. They posed him this riddle because Jesus was of the rival school of the Pharisees—which may sound strange, given how often he clashed with the Pharisees in the Gospels, but it’s probable that these clashes were so intense precisely because they were internal debates, which are often far more tinged with bitterness than conflicts with expected opponents. The riddle the Sadducees came up with seems to be a parody of the book of Tobit, whose canonical status (if I understand correctly) was a little nebulous at the time; there were Aramaic and Hebrew versions of Tobit, and one of these was probably the original language of its composition, but it is much more familiar in Greek, so it seems likely that it was esteemed more by Hellenist Jews than Pharisees in Palestine.

Anyway, the Sadducees set forth this riddle—I assume, while making air quotes with their fingers—modeled on one of those countless “it’s not the Torah but it’s still divine, trust me bro” books those Pharisees are so into. Jesus begins by not taking the bait. Their thinly-veiled critique of the wider Pharisaic canon seems like an obvious dare to defend that canon; if so, his reply lands like a slap in the face. “Ye do err, not knowing the Scriptures, nor the power of God”: a rude enough thing to say publicly to anyone, let alone professional clergy! Then he explains that the problem is illusory, because in the resurrection people “are as the angels”—the existence of angels being the one big disagreement which the Sadducees’ riddle does not touch upon, as if Jesus is helpfully point out “You forgot this last thing you’re wrong about, by the way.”

Romans 14:4

Who art thou that judgest another man’s servant? to his own master he standeth or falleth. Yea, he shall be holden up: for God is able to make him stand.

In my opinion, this single text provides an adequate and complete answer to every—every—objection people raise to using LGBT terminology as a Christian.

Psalm 34:18

The LORD is nigh unto them that are of a broken heart;

and saveth such as be of a contrite spirit.

I doubt that I need to tell any LGBT person the way this verse can pertain to us, but I’ll highlight a few for my cis-het brethren:

- We may be rejected, abused, disowned, or thrown out by our families for telling them the truth about our orientations or gender identities.

- We may be pressured to embark on ill-considered marriages (which can ruin entire lives and families) by families and churches that prefer to ignore us.

- We may be unable to pursue marriage or parenthood in a church we’re deeply devoted to.

- We may hear people like ourselves denounced as uniquely evil from the pulpit.

- We may struggle for years or decades to “become straight” or “accept our bodies,” and feel overwhelming guilt and shame over our inability to do so.

- We may feel cut off from friends and loved ones because we don’t dare share our secret with them.

- We may find ourselves viewed and treated as inherently predatory, or morally warped in general, and barred from ministry (even informal ministry).

- We may find our non-erotic needs and desires for camaraderie, affection, attention, and touch automatically classified as sexual and/or pathological.

- We may find our orthodoxy or credibility impugned, for no reason except our LGBT identities.

I can tell you right now, cis-het brethren: Not only does none of this stuff feel good, none of it’s good for you, mentally. Admittedly, some people handle it better than others. But imagine you were at church one morning, and that at after-Mass coffee, you said something in passing (you probably can’t even recall what) that clearly implied you’re straight. Now imagine that later that week, you got an email from the pastor’s office telling you, as gently as possible, that somebody with your condition teaching children’s Sunday school—several parents have already said they’re uncomfortable—anyway, the pastor wants you to know how deeply he and the congregation care about you. The decision to ban you from teaching Sunday school (effective immediately) has already been made, you’re just being notified. I hope you would be stunned; I feel sure you’d be angry; but look at the verse again, there’s something else you might be—heartbroken.

I don’t totally get what it means for God to be “near” the broken-hearted. One meaning that does spring to mind, though, is that God does not sneer at our pain: doesn’t tell us we’re being manipulative: doesn’t archly suggest that all this shows a lack of faith on our part. He doesn’t tell us we don’t matter.

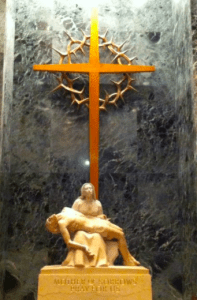

The Chapel of Our Lady of Sorrows,

Patroness of Slovakia, at DC’s Basilica of

the Immaculate Conception.

I Samuel 1:1-8

Now there was a certain man … of mount Ephraim, and his name was Elkanah … And he had two wives; the name of the one was Hannah, and the name of the other Peninnah: and Peninnah had children, but Hannah had no children. … And when the time was that Elkanah offered, he gave to Peninnah his wife, and to all her sons and her daughters, portions: but unto Hannah he gave a worthy portion; for he loved Hannah: but the Lord had shut up her womb. And her adversary also provoked her sore, for to make her fret, because the Lord had shut up her womb. … [T]herefore she wept, and did not eat. Then said Elkanah her husband to her, “Hannah, why weepest thou? and why eatest thou not? and why is thy heart grieved? am not I better to thee than ten sons?”

Hannah was the mother of Samuel (the pivotal figure in Israel’s transition from the time of the judges to the monarchy. Hannah’s adversary, Peninnah, was apparently a real classy lady—but let’s think this out a little. We’re told Elkanah loved Hannah; we’re told nothing about his feelings toward Peninnah, suggesting that she may have been, or at any rate felt, neglected. Elkanah may seem like a simp who can’t keep his house in order, and/or is oblivious to Peninnah’s maltreatment of Hannah; then again, what would we like Elkanah to do? Embarrass both his wives by openly calling out Peninnah’s bullying, and thus risk any domestic peace the family did have? Or are we to blame Hannah for not standing up for herself, when her position was almost as precarious as it was possible to be?

Anyway. Speaking for myself, the sting here is in the final question: “Am I not more to thee than ten sons?” came into my mind once at Mass, not long after I finished college. I don’t recall what my answer was at the time, or whether I even had one, but the truthful answer at present is “No, Lord, you aren’t.” And it hurts.

No, I didn’t join the Church in order to have children. And her doctrines aren’t secret or anything—this is not about being caught off-guard. But it can still hurt, and does, to know that even if it were financially and personally viable, if I had a partner and we adopted a child, I’d have to fight to get that child access to the sacraments; that our family would be continually vulnerable to any amount of nastiness from fellow parishioners, pastors, even diocesan authorities—that, one day, I would have to try to explain to my child why our fellow Catholics treated us like this—and that all of this would not be changed at all even if my partner and I “lived as brothers” in perfect chastity. The only way they would leave off so treating us would be if my partner and I split up and one or both of us got into a sham marriage, even if we were unfaithful to our wives. Because most Catholics really don’t care about chastity, any more than they care about being strictly truthful. They care about appearances, especially appearances they can marshal into a claim on political power, because they’ve persuaded themselves that this somehow serves the gospel.

Samuel Dedicated by Hannah at the Temple

(date unknown—late 19th or early 20th c.),

by Frank W. W. Topham.

“Her adversary provoked her sore, to make her fret.” Precisely what this whole “reclaiming June for the Sacred Heart” stuff avowedly is.

This is tragic. It is a grievous mistake about the fundamental nature of our religion—a mistake that chews people up and spits them out in the ostensible service of humanity.

This may prompt both sympathetic and sneering outside observers to ask, “Why even be a Catholic?” I summarized my answer once in a poem: There is no place that I would rather die. The reasons for that in turn are complicated; story for another time. Three more texts to come—those will be in Chapter Three.