We Can Serve Both God and Mammon, Right?

No.

The Worship of Mammon (1909),

by Evelyn De Morgan.

Moving on.

Luke 16:1-13, RSV-CE

He also said to the disciples, “There was a rich man who had a steward,a and charges were brought to him that this manb was wasting his goods. And he called him and said to him, ‘What is this that I hear about you? Turn in the account of your stewardship, for you can no longer be steward.’ And the steward said to himself, ‘What shall I do, since my master is taking the stewardship away from me? I am not strong enough to dig,c and I am ashamed to beg. I have decided what to do, so that people may receive me into their houses when I am put out of the stewardship.’ So, summoning his master’s debtors one by one, he said to the first, ‘How much do you owe my master?’ He said, ‘A hundred measuresd of oil.’ And he said to him, ‘Take your bill,e and sit down quickly and write fifty.’ Then he said to another, ‘And how much do you owe?’ He said, ‘A hundred measuresd of wheat.’ He said to him, ‘Take your bill, and write eighty.’ The master commended the dishonest steward for his prudence; for the sons of this world are wiser in their own generation than the sons of light.f And I tell you,g make friends for yourselves by means of unrighteous mammon,h so that when it fails they may receive you into the eternal habitations.

“He who is faithful in a very little is faithful also in much; and he who is dishonest in a very little is dishonest also in much. If then you have not been faithful in the unrighteous mammon, who will entrust to you the true riches? And if you have not been faithful in that which is another’s, who will give you that which is your own? No servant can servei two masters; for either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and mammon.”

The sigil of Paimon1 from Samuel MacGregor

Mathers’ version of The Lesser Key of Solomon.

Paimon is often associated with wealth; he is

the background antagonist of Hereditary.

Luke 16:1-13, my translation

And he said to his students: “There was a rich person who had a house-manager,a and the latter was accused to the formerb as squandering his belongings. And calling him, he tells him, ‘What is this I hear about you? Give back a word on your house-management, for you cannot house-manage any more.’

“So the house-manager says to himself, ‘What will I do? because my lord is removing the house-management from me. To dig—I do not have the strength;c to beg—I am ashamed. I know what I will do, in order that whenever I am deposed from household-management, they ought to receive me into their own homes.’ And calling each one of his own lord’s loan-debtors, he said to the first, ‘How much do you owe to my lord?’ He tells him, ‘A hundred batsd of olive [oil].’ And he says to him, ‘Take your note,e sit down, and quickly write fifty.’ After that, to another person, he says, ‘How much do you owe?’ He says, ‘A hundred korsd of grain’; he says to him, ‘Take your note and write eighty.’

“And the lord applauded the house-manager of injustice because he had acted sensibly; because the sons of this age are more sensible than the sons of light are in their own generation.f And I say to you,g get yourselves loved ones from the Mammonh of injustice, in order that whenever it fails, they ought to receive you into the eternal tents.

“He who is faithful in the smallest thing is also faithful in much, and he who is unjust in the smallest thing is also unjust in much. If, then, you were not faithful in unjust Mammon, who will have faith in you for the true? And if you were not faithful in another’s things, who will give you your own? No one is able to slave as a servanti for two lords: for either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will adhere to the one and despise the other. You cannot slave for God and for Mammon.”

Textual Notes

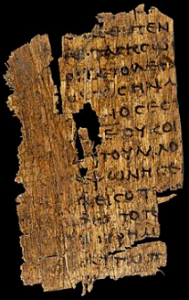

Papyrus 69, generally considered a fragment of

the Gospel of Luke, but conjectured to be from

the Gospel of Marcion.2

a. steward/house-manager | οἰκονόμον [oikonomon]: This term (οἰκονόμος [oikonomos] in dictionary form) is of course the origin of the English word economy: that is, “household law” (partly because the household was the basic economic unit of pre-industrial societies). However, οἰκονόμος is not an abstract term in Greek like economy is in English. It referred to a position overseeing a household, which would principally mean attending to the household slaves: giving them their food, keeping them on task, resolving quarrels and stopping fights, administering punishments, etc. Luke names one of Jesus’ prominent female disciples, Joanna (who helped finance his ministry and is traditionally counted as a myrrh-bearer3 in the East), as the wife of Herod Antipas’ οἰκονόμος, Chuza.

“Wife” is significant there. Slaves, since they had no legal personhood, were unable to marry—but this position in a household was not usually held by a slave. Normally, an οἰκονόμος would be a free person, albeit probably a freedman rather than someone free-born. As in the American slave system, freedmen were still expected to contribute to their former master’s household. Given the duties of an οἰκονόμος, one can see the logic having a freedman as a sort of go-between: someone who is free on the one hand (maybe not fully autonomous, but a legal person, at least) and yet has experience of the slave status on the other; his power over the slaves would be unambiguous and absolute, yet enhanced by sympathy, envy, or both in a way even the master’s could not. It’s a cynical logic, but it’s a logic.

b. charges were brought to him that this man/the latter was accused to the former | οὗτος διεβλήθη αὐτῷ [houtos dieblēthē autō]: The verb here is a form of διαβάλλω [diaballō], literally meaning “to throw across.” It thus came to mean “accuse, slander,” the accent being on the accuser’s malice, whether the accusation in itself were correct or not. It is also the root of διάβολος [diabolos], “accuser,” borrowed (via Latin diabolus) as early as the Anglo-Saxon period, probably in the form ᛞᛖᚩᚠᚩᛚ [deofol] or ᛞᛖᛇᚠᚩᛚ [dēofol],4 descending to us in Modern English as “devil.”

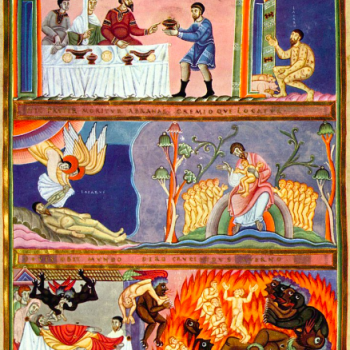

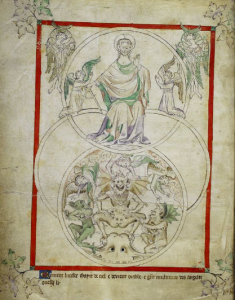

Christ and Satan from an illumination in the

Queen Mary Psalter (early 14th c.)

My use of “the latter” and “the former” is a bit of linguistic license. The basic meaning of οὗτος is simply “this,” frequently serving as a pronoun (so “this one, this man”); αὐτῷ is the dative form of αὐτός [autos], a word originally meaning “(him)self” but also serving as an all-purpose pronoun in New Testament Greek. So a more literal rendering would be “this one was accused to him,” and the broader context of the parable makes it clear which pronoun applies to which of the two characters thus far mentioned.

c. I am not strong enough to dig/To dig—I do not have the strength | σκάπτειν οὐκ ἰσχύω [skaptein ouk ischüō]: Digging was an important form of what’s now called “unskilled labor” (a label that smacks both of untruth and ingratitude, but never mind). According to the lexicographers at Bible Hub, it was common at the time to dig through as much as nine feet of topsoil to be able to set the foundations of a building directly on the bedrock. Besides being filthy, back-breaking work to do by hand, it required considerable time, meaning that patience, perseverance, and foresight were as important as raw physical strength; as said lexicographers note, this professed inability, perhaps really just reluctance, lends color to the charge of misappropriation that has been brought against this manager.

d. measures … measures/bats … kors | βάτους … κόρους [batous … korous]: The בַּת [bat or bath]5 and כֹּר [kor] were Hebraic units of measurement, the first liquid and the second dry. The common unit of liquid measure was the לֹג [log], around an eighth of a gallon; twelve logs made one הִין [hyn], and six hyns made one bat, which was therefore roughly equivalent to nine gallons … probably. (Put mildly, there seems to be some debate about the exact amounts these units represent, and standardization may have been very imperfect—it often was in the ancient world.) For dry measurement, the עֹמֶר [uomer] was equivalent to a little over three and a half pounds, with ten uomers to the אֵיפָה [‘êyfâh] and ten ‘êyfâhs to the kor, putting the kor somewhere around 350-400 pounds (again, probably).

e. bill/note | τὰ γράμματα [ta grammata]: The most literal rendering here would be “letters,” which in the ancient world also functioned as numerals. The idea of using distinct signs that only indicate numerals came from India; it did not reach the Mediterranean until the seventh century, at which point it was adopted by the Muslim intelligentsia. The concept was introduced in Europe by the tenth century, but seems to have had few or no advocates before Leonardo fi’Bonacci’s6 Book of the Abacus in 1202, and didn’t really catch on until the invention of printing.

f. the sons of this world are wiser in their own generation than the sons of light/the sons of this age are more sensible than the sons of light are in their own generation | οἱ υἱοὶ τοῦ αἰῶνος τούτου φρονιμώτεροι ὑπὲρ τοὺς υἱοὺς τοῦ φωτὸς εἰς τὴν γενεὰν τὴν ἑαυτῶν εἰσιν [hoi huioi tou aiōnos toutou fronimōteroi hüper tous huious tou fōtos eis tēn genean tēn heautōn eisin]: This one, … hoo. I really don’t know if I’m picking up what our Lord is putting down here! My best guess is something like: “Those whose minds and outlook are shaped by this fallen order (if they are shrewd, at least) know how to play things to their advantage (as in the example of the dishonest oikonomos just given); but the sons of light—you, my disciples—have hardly learnt how to understand the divine economy at all, let alone play it to your advantage.”

g. I tell you/I say to you | ἐγὼ ὑμῖν λέγω [egō hümin legō]: The formula ὑμῖν λέγω or λέγω ὑμῖν is a fairly frequent one on Jesus’ lips in the Gospels, but with a difference that I take to be significant: it normally follows the word ἀμήν [amēn], which I imagine my readers will recognize!—not Greek, but a loan-word from Hebrew (אָמֵן [‘âmên]). “Amen” was used to indicate religious assent or approval, for instance of a prayer; this usage has continued among some Christians to this very day. Jesus putting the word first (kind of a pre-emptive religious declaration of his words’ legitimacy) is a rhetorical device that, so far as I know, is unparalleled. The omission of that word here, together with the, shall we say, strangely counter-intuitive advice the Lord gives immediately after it, makes me think that this is actually a piece of sarcasm rather than something tortuously subtle.

h. mammon/Mammon | μαμωνᾷ [mamōna]: This is not a Greek word, but another loan, this time from the Aramaic מָמוֹנָא [mâmounâ’], “wealth, riches.” Mammon is often described as a Syriac god of wealth, which makes sense—except that there appears to be no archæological evidence, and little or no literary evidence, that any deity was known by such a name in contemporary Syria. There were Roman gods that more or less fit the profile, like Plutus (often merged with the god of the dead, Dis Pater), but they of course were named in Latin. It’s possible that the personification here is not an allusion to a pagan god, but Jesus’ own device.

Mosaic from a Roman villa in modern Tunisia

showing a woman attended by two slaves.

Photo by Fabien Dany, used under

a CC BY-SA 2.5 license (source).

i. servant … serve/slave as a servant | οἰκέτης … δουλεύειν [oiketēs … douleuein]: This is kind of a fascinating juxtaposition. Δουλεύω [douleuō] is a standard verb meaning “to slave (for), serve,” derived from the noun δοῦλος [doulos], “slave”; οἰκέτης, on the other hand, is ultimately a derivative of οἶκος [oikos], “house(hold).” An οἰκέτης was not a common slave, but a trusted member of the household: don’t think Jim from Huckleberry Finn so much as Samwise in The Lord of the Rings.

Gotta Serve Somebody

The claim with which I opened, that you cannot serve both God and Mammon, is not an original one—I mean, obviously; we just went over whomst I’m getting it from. American culture does seem, to me, to have a particularly difficult time accepting this either-or, the fact that there’s no secret third option that nets us the perks of both pursuing earthly riches as our principal goal in this life, and also not going to hell after it. There is, of course, the possibility of deathbed repentance; sincere repentance is always accepted by heaven, howsoever late it may be. The catch in that, though, is that when you’ve trained yourself, through decades of practice, to make the wrong choice when it counts, it is exceedingly difficult to break your own pattern and make the right choice when it really, really counts—especially when you likely don’t have the aid of a concrete object of choice, an incarnating symbol of the thing you’re choosing. (It’s not impossible to have such a thing on one’s deathbed, but they aren’t abundant, just because there are so few actions one can take in those circumstances.)

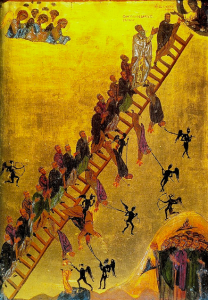

The Ladder of Divine Ascent (late 12th c.),

written anonymously, preserved in

St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai,

Egypt.

I’ve lied, of course. I said the catch just now; there are two. The other one is, you have no idea when you’re going to die.

Does that sound like I’m trying to frighten you? I am, a little; in the same sense I’m trying to frighten myself. What I am really trying to do is get myself, and you also, to reckon seriously with the Four Last Things, because it’s just TRUE that none of us knows when we’re going to die. There is no number of talentless homilists or fifth-rate devotional writers using memento mori as a cheap scare tactic that can make death go away.

Some day, you will face that moment. Regardless of what you believe, at that moment either you will face complete nonexistence, which is something you can’t possibly imagine, or you will face something even stranger that you also can’t possibly imagine. On an actual day in the future, you will be in the unimaginable …

—David Wong, John Dies at the End

Footnotes

1I can’t prove this, but I have a hunch that Paimon is a garbling of the name Mammon.

2Marcion was a prominent theologian from the province of Asia (the west of modern Turkey) who founded a rival, Gnostic church in the mid-second century; he traveled to Rome in the 130s, but was excommunicated in 144 for his heretical beliefs. He reputedly recognized St. Paul alone as a genuine apostle of Jesus, and had a New Testament of his own devising, including what was by all surviving accounts a mutilated version of the Gospel of Luke, one that expurgated all that nasty “Incarnation” stuff; this work has been lost. (I learned several months back from the YouTube channel Religion for Breakfast—which is usually much better than this, for the record!—of a truly stupid project to reconstruct the Gospel of Marcion. I say “stupid,” not because I would automatically object to such a thing; on the contrary, I’d find it quite interesting, if a reliable reconstruction were possible. But, on hearing exactly how they’re making the attempt, which is claiming precision down to the individual word, I immediately came up with five simple technical issues in the methodology plus four big, project-destroying problems in its fundamental assumptions … literally none of which, as far as I know, have been addressed. Don’t play the video at that link in the hearing of a statistician without warning them first, their heads will explode.)

3Myrrh-bearers is a title for those who came to tend Jesus’ body after his death, of which there are two groups. The first, and the only men, are St. Joseph of Arimathea and St. Nicodemus, who did what they could on Good Friday itself when Jesus was taken down from the Cross. The second group of myrrh-bearers are all women, those who went intending to finish the embalming on Easter Sunday, and were accordingly the first witnesses of the Resurrection. Besides St. Joanna, they include St. Mary Magdalene, St. Mary of Clopas (thought to be the sister of the Virgin), SS. Mary and Martha of Bethany, St. Mary Salome (the wife of Zebedee and mother of SS. John and James the Greater), and St. Susanna (also mentioned in Luke 8), and it is believed that there were more whose names have been lost. Conspicuously, the Mother of God is not among them: there is a widely-held opinion among theologians that she was the first person Jesus went to after his Resurrection, which might explain both why she is never clearly listed among the myrrh-bearers in Scripture and why Jesus at first seems to be absent not only from the tomb itself, but from its vicinity, in all four canonical Gospels. Only in John does he appear to anyone even while they are near the tomb. (As for why Scripture wouldn’t record this meeting between the Lord and his Mother, there could be any number of reasons—but the one that impresses itself on my mind is, they were both human beings: maybe this, of all moments, was a private one that just they shared and we don’t need to get nosy about it.)

4Note that in typical Anglo-Saxon pronunciation, the fricatives f, s, and þ (pronounced like the th of “thin”), which were unvoiced by default, shifted to their voiced equivalents between two vowels, becoming v, z, and ð (pronounced like the th of “this”); accordingly, although spelled with ᚠ (or f by scribes using the Roman script), both spellings proposed above would have been pronounced “deovol,” with the e and o run together as a diphthong. Since the i in the modern term, being an unstressed vowel, is reduced by most speakers to a ə (“schwa”), this word has changed far more in appearance than in actual sound over the last thousand-odd years!

5Normally I would use the transcription bath. I went with bat here to avoid confusion with “bath” in the “-tub” sense.

6The more usual style Fibonacci misrepresents the name slightly; it is not a surname, but a patronymic: figlio Bonacci, “son of Bonacci.”