Foliage and fruit of the sycamore-fig, a type of

fig that grows in Africa and the Levant. Photo

by Atamari, used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license

(source).

John 1:47-51, RSV-CE

Jesus saw Nathanael coming to him, and said of him, “Behold, an Israelite indeed, in whom is no guile!” Nathanael said to him, “How do you know me?” Jesus answered him, “Before Philip called you, when you were under the fig tree, I saw you.” Nathanael answered him, “Rabbi, you are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!” Jesus answered him, “Because I said to you, I saw you under the fig tree, do you believe? You shall see greater things than these.” And he said to him, “Truly, truly, I say to you, you will see heaven opened, and the angels of God ascending and descending upon the Son of man.”

John 1:47-51, my translation

Jesus saw Nathanael coming toward him and said about him, “Look, truly, an Israelite, in whom there is no bait.”

Nathanael said to him, “How do you know me?”

Jesus replied and told him: “Before Philip called you, while you were under the fig, I saw you.”

Nathanael replied to him, “Rabbi, you are the Son of God, you are king of Israel.”

Jesus replied and told him, “Because I told you that I saw you underneath the fig, you have faith? You will see bigger things than that.” And he said to him, “You will see heaven opened and the messengers of God going up and going down on the Son of Man.”

Textual Notes

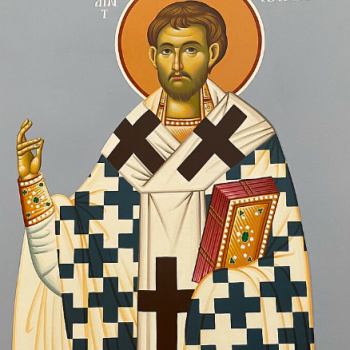

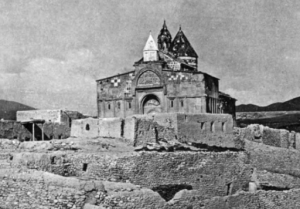

Ruins of St. Bartholomew’s Monastery, at what

is traditionally held to be the site of his martyr-

dom in what was then Armenia (now the

extreme east of Turkey).

a. Nathanael | Ναθαναὴλ [Nathanaēl]: Nathanael is generally identified with St. Bartholomew, which makes some sense, since most of the apostles are known to us by forenames, and Bartholomew—more exactly, bar-Tolmai—is a patronymic; John never mentions a Bartholomew, and none of the Synoptics mention a Nathanael, though this by itself is less informative than it may appear, since John (unlike the Synoptics) includes no list of the Twelve; moreover, SS. Philip and Bartholomew tend to appear as a pair in the Synoptics, and Philip is closely associated with Nathanael in John. (Some authorities, though a minority, do identify Nathanael with some other figure, such as St. Simon the Cananæan, as both appear to be from Cana.) Why he is known by his surname elsewhere, or why John gives us his forename, I don’t know; perhaps for some personal reason of which we could hardly expect to know.

b. guile/bait | δόλος [dolos]: “Bait,” and thus by extension a trap or lure, was the original meaning of δόλος. Thanks, hilariously, to internet culture, the word “bait” in English has become more current among non-anglers, to the point that its use here is practical.

c. you are the Son of God | σὺ εἶ ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ θεοῦ [sü ei ho huios tou theou]: I am not sure whether to take this as Nathanael changing his mind or being sarcastic. The former seems more in concert with the general movement of this part of the Gospel of John: John 1:29-51 opens with the Baptist’s direct witness (and his description of Christ’s baptism, which the other three evangelists recount directly), and from there moves on to the gathering of the first few apostles—St. Andrew, “another disciple” (generally interpreted as St. John himself), St. Peter (who receives his new name right at the start here), St. Philip, and now Nathanael/St. Bartholomew.

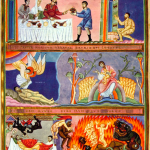

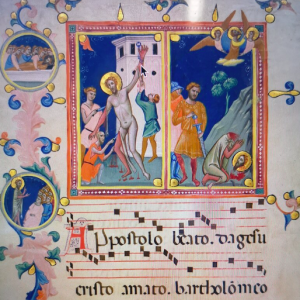

The martyrdom of St. Bartholomew1 (ca. 1340)

by Pacino di Bonaguida, a Florentine illuminator.

Photo by Wikimedia contributor Slackgab, used

under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

On the other hand, taking it as sarcasm makes a little more sense on the face of it. Strictly speaking, Jesus has not clearly claimed to have done anything unusual—it’s not that weird to notice someone underneath a tree—and really, it’s not even clear that he’s directly answered Nathanael’s question (how does “I saw you under that tree” answer “How do you know my character?”). But then, if the tree in question were in some spot that clearly didn’t allow for mere chance noticing of people, and Nathanael had been doing something while there that exhibited his character (praying, for example), then a straight, non-sarcastic read would make more sense. On balance, I think I favor the non-sarcastic interpretation, but I’m not certain.

d. the Son of Man | τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ ἀνθρώπου [ton huion tou anthrōpou]: This title is interesting. It probably looks especially unassuming next to the title “Son of God” that Nathanael has just used, whether in jest or straightforwardly. However, additional background in the Hebrew Bible may suggest that, of the two titles, “Son of God” is the milder one, whereas “Son of Man” may have a note of audacity to it.

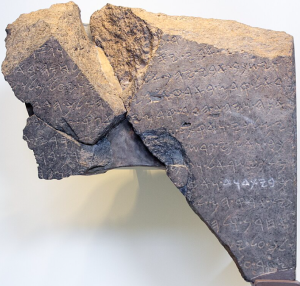

The Tel Dan Stele (9th/8th c. BC), widely

considered the earliest non-Biblical reference

to the House of David. Photo by Oren Rozen,

used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

The explanation for the character of both titles is to be found in the third division of the Hebrew Bible, the Kethuvim (“Writings”). Specifically, we may go to the Psalms for the title Nathanael uses for Jesus, and to Daniel for the title Jesus uses for himself. Psalm 2 runs as follows:

Why do the heathen rage,

…..and the people imagine a vain thing?

The kings of the earth set themselves,

…..and the rulers take counsel together,

against the Lord,

…..and against his anointed, saying,

“Let us break their bands asunder,

…..and cast away their cords from us.”

He that sitteth in the heavens shall laugh:

…..the Lord shall have them in derision.

Then shall he speak unto them in his wrath,

…..and vex them in his sore displeasure.

“Yet have I set my king upon my holy hill of Zion.”

I will declare the decree:

…..the Lord hath said unto me,

“Thou art my Son;

…..this day have I begotten thee.

Ask of me, and I shall give thee the heathen for thine inheritance,

…..and the uttermost parts of the earth for thy possession.

Thou shalt break them with a rod of iron;

…..thou shalt dash them in pieces like a potter’s vessel.

Be wise now therefore, O ye kings:

…..be instructed, ye judges of the earth.

Serve the Lord with fear,

…..and rejoice with trembling.

Kiss the Son, lest he be angry,

…..and ye perish from the way, when his wrath is kindled but a little.

Blessed are all they that put their trust in him.

This was a royal psalm, used in coronations in the Kingdom of Judah. Rather than being crowned, Judahite kings were anointed; it used to be thought that this ritual was borrowed from Egyptian society, but more recent scholars have called this into question—it may have been a practice native to the Levant. In any case, it seems to have been a way of designating someone a representative of the monarch. In Judaic usage, God was held to be the proper king of the Hebrew people, and kings were anointed accordingly; prophets and priests were also anointed for the same reason. Monarchs, however, as this psalm exhibits, were also called, or at any rate spoken of as, “the son of God.” Accordingly, while there was some room for interpretation, “son of God” could be taken simply as a Davidic title.

The Stepped Stone Structure, seen from the

Large Stone Structure.2 Photo by Wikimedia

contributor Omerm, used under

a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

To avoid misunderstandings, this doesn’t mean the title “Son of God” never meant more than this; it certainly did, and during the first century. The Davidic meaning would only have been recognized in, and relevant to, Jews. The Greek Θεοῦ Υἱός [Theou Huios], “God’s Son,” so well known from the “Jesus fish,”3 corresponded pretty nearly to one of the titles of the Cæsars: Dīvī Fīlius, “Son of the Divine [Julius],” a title first given to Augustus as Julius Cæsar’s adopted son and thereafter passed down to later emperors.

And what about “Son of Man”? The Gospels are not the first books of the Bible in which this title appears; at least two other books use it, Ezekiel and Daniel. Now, in Ezekiel, who dates to the early-to-mid sixth century BC, the title seems to be a comparatively humdrum one, meaning little more than “human being, person.” By association, it could maybe be interpreted thereafter as “prophet, oracle, seer”; Ezekiel certainly has some of the most remarkably dramatic visions of any of the Biblical prophets.

But then there’s Daniel. A literalistic reading places both the man and the book in the mid-to-late sixth century; the modern academic consensus usually considers Daniel the person fictitious, and places the book in the second century BC.4 Either way, he came later than Ezekiel; and its author uses the phrase “son of man” for a quite different purpose.

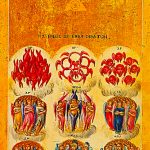

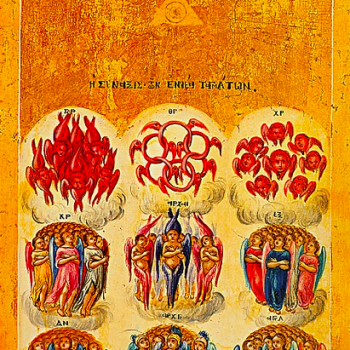

An illumination of Christ among the Seven

Lampstands in Revelation 1 from the

Bamberg Apocalypse (11th c.).

In the first year of Belshazzar king of Babylon Daniel had a dream and visions of his head upon his bed … I saw in my vision by night, and, behold, the four winds of the heaven strove upon the great sea. And four great beasts came up from the sea … [T]hey had their dominion taken away: yet their lives were prolonged for a season and time.

I saw in the night visions, and, behold, one like the Son of man came with the clouds of heaven, and came to the Ancient of days, and they brought him near before him. And there was given him dominion, and glory, and a kingdom, that all people, nations, and languages, should serve him: his dominion is an everlasting dominion, which shall not pass away, and his kingdom that which shall not be destroyed.

… These great beasts, which are four, are four kings, which shall arise out of the earth. But the saints of the most High shall take the kingdom, and possess the kingdom for ever, even for ever and ever. Then I would know the truth of the fourth beast, which was diverse from all the others, exceeding dreadful, whose teeth were of iron, and his nails of brass; which devoured, brake in pieces, and stamped the residue with his feet; and of the ten horns that were in his head, and of the other which came up … I beheld, and the same horn made war with the saints, and prevailed against them; until the Ancient of days came, and judgment was given to the saints of the most High; and the time came that the saints possessed the kingdom.

—Daniel 7:1-3, 12-14, 17-22

As used here, “one like the Son of man” is a messianic, apocalyptic figure; and especially if the present academic consensus is correct about the book of Daniel being composed during the Maccabees’ era, less than two hundred years before the time of Christ, it is this meaning for the phrase, rather than Ezekiel’s, which was likely top of mind for those who heard it. Jesus’ allusion here to “angels ascending and descending upon the Son of Man” also invites an apocalyptic reading, echoing the “Jacob’s ladder” episode in Genesis. The combination of this image (Jesus as the bridge between heaven and earth) with the use of the two titles “Son of God” and “Son of Man” so closely juxtaposed, can even be read as an allusion to the doctrine of the Incarnation, which John places front and center.

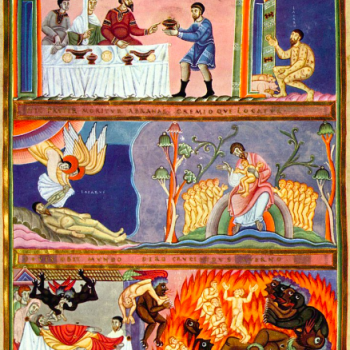

A Russian Orthodox celebration of the Divine

Liturgy of St. James, during the consecration;

the deacon (in gold at the far right) is fanning

the elements.5

Footnotes

1According to the most familiar traditional account, St. Bartholomew (who along with St. Jude is supposed to have evangelized Armenia, then a more expansive kingdom ruling much of the Armenian Highlands and Caucasus Mountains) was martyred by being, among other things, flensed—that is, skinned. He is often depicted holding his skin for this reason, e.g. in Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, occupying the altar-end wall of the Sistine Chapel. Di Bonaguida, for reasons best known to himself, chose to represent the apostle in the right-hand panel above as still wearing his skin, but wearing it more like a cloak or cape than like, well, skin.

2When she originally discovered it in 1997, Israeli archæologist Eilat Mazar interpreted her find as the Palace of David; other researchers were skeptical, and it was dubbed the Large Stone Structure. (I personally feel—though this is not relevant to whether her interpretation was correct—that they did not work as hard on this name as she did on discovering the Large Stone Structure.) The Stepped Stone Structure, which is connected to it, appears to be the Millo (mentioned e.g. in II Kings 12), a term whose meaning is not entirely clear, but which may mean “the landfill” or “the retaining wall.”

3The Greek word for “fish” is ἰχθύς [ichthüs]; it so happens that this forms a convenient acronym for Ἰησοῦς Χρῑστός Θεοῦ Υἱός Σωτήρ [Iēsous Christos Theou Huios Sōtēr]: “Jesus, Anointed, God’s Son, Savior.” (Anointed probably meant little to most Romans or Greeks, but Savior, or Healer, was another imperial title—one that makes more sense in light of the fact that imperial rule put an end to over a hundred years of civil conflict in Rome, in a time when Rome’s problems were ipso facto the whole Mediterranean’s problems.) This was recognized at a very ancient date, and the association of both Jesus and most of his disciples with fish lent the phrase color, so that the image of the fish was sometimes used as a coded symbol by Christians during periods when they needed to remain underground to avoid legal consequences.

4I’d be inclined to split the difference here. Judahite elites were taken into exile in Babylon, after all, so the premise of the book of Daniel isn’t exactly outlandish (no pun intended), nor is the name a huge stretch for an ancient Jew; it seems perfectly plausible to me that an intelligent Jew trained in the Babylonian academy could have become a member of the administration of Nebuchadrezzar II (a.k.a. Nebuchadnezzar II), and perhaps lived long enough to be “passed on” to Cyrus when he took over, ca. 540 BC. It also seems pretty credible that such a figure’s story could have been preserved, with or without romantic embroidery of the facts, and used as a framing device for apocalyptic commentary in the crisis of the second century, when the Seleucids were attempting to destroy Judaism altogether.

5The Divine Liturgy of St. James is an exceedingly ancient liturgy, celebrated by some Eastern and Oriental Orthodox Christians, and by the Maronite and Melkite Catholic Churches, whose origins lie in Lebanon and Syria. Ripidia, or liturgical fans (sg. ripidion), are used in this rite, though not as westerners might expect: ripidia have small bells along their edges, and they are shaken (rather than waved) at certain points during the consecration of the Eucharist. Despite the dramatic difference in shape, they are analogous in both sound and function to Latin altar bells (a.k.a. the sacring or sanctus bell). Ripidia are traditionally decorated with images of the seraphim.