In case you haven’t already heard (and how could you not?), there’s an epidemic sweeping the nation this fall. Disturbing, garishly-dressed figures have been spotted all over the country — lurking in dark corners, walking slowly along isolated rural roads, hanging out near schools and playgrounds, trying to lure the innocent into the woods with promises of candy and other great, huge, terrifically great things. Recently, White House press secretary Josh Earnest tried to calm the increasing national panic. Even the Daily Show has covered the news.

That’s right, America, we have a serious problem: Creepy Clowns.

B.O.L.O. The Clown

It all started back in August.

Early in the month, a sinister figure known as “Gags the Clown” began appearing in Green Bay, Wisconsin, and (more importantly) on Facebook. This creepy clown, dressed in eerily gothic, soiled circus garb and holding a bunch of black balloons, was spotted lurking in various isolated nighttime locales. Captured in grainy vintage-filter photographs posted to social media, the unidentified clown soon sparked wide-spread media coverage — including not just The New York Times, NPR and USA Today, but also making international news in Germany, Ireland and New Zealand — and even some alien conspiracy theories. But only a week after the initial sightings, with the Facebook page already boasting more than 50k likes, Gags the Clown was revealed to be no more than an ambitious independent filmmaker named Adam Krause trying to hype his latest horror movie project.

The incidents in Greenville, South Carolina, however, were not so easily explained away.

On August 24, residents of the Fleetwood Manor apartments found a letter from the property manager posted on their doors. It warned of recent clown sightings in the area and reminded parents to abide by the building’s policies about supervising children at all times and keeping them inside after the 10 PM curfew. Local news reporters confirmed that the police had received complaints earlier in the week from several different sources, describing clowns hanging out by nearby woods, knocking on people’s doors, standing under streetlights at night and, in one case, a clown doing his laundry at a laundromat (still wearing his curly wig, red nose and face paint, but dressed in gray sweats — presumably because his regular outfit was in the wash).

Police appeared on local news outlets to encourage people both to stay calm, and also to immediately report any suspicious or strange behavior, assuring the public that they were taking the reports seriously. Meanwhile, local residents began posting pictures of the warning letter on Facebook and Twitter, supplemented by a heavy dose of stock images of creepy clowns and screenshots from B horror movies.

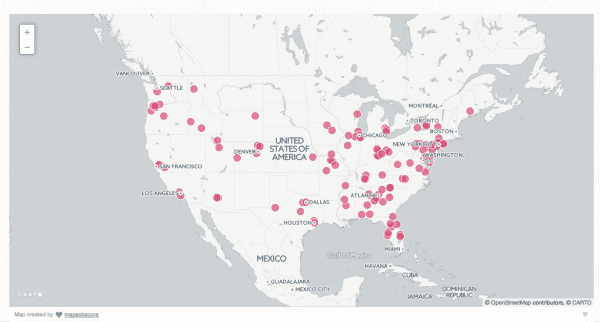

From there, the sightings spread. First to nearby counties in South and North Carolina, than throughout the American south, traveling northward up the east coast, then heading west, into the heartland until, in late September, sightings began to be reported in California, Oregon and Washington. As of last week, the epidemic has gone global, with creepy clowns reported in Canada, the UK, Ireland, Denmark, and Australia.

For FOAF’s Sake! The Phantom Clown Theory

The creepy clown epidemic spread — as its name implies — like a virus moving from person to person. But the pattern of increasing sightings also follows the typical behavior you might expect to see in the creation and spread of an urban legend. Although the rumor mill of local newspapers and social media continued to churn out stories about creepy clowns lurking around every corner, during the first several weeks of this growing epidemic no actual clowns were ever photographed or detained by police. Yet the stories kept coming.

This wasn’t the first time such rumors had spread across the country. In fact, spikes in creepy clown sightings seem to happen every few years in a repeating cycle. This cycle is regular enough that it even has a name: The Phantom Clown Theory, coined by author Loren Coleman back in 1981.

According to Coleman, there are several distinct attributes that characterize the Phantom Clown phenomenon:

- The “creepy clown” is usually seen hanging out by playgrounds, parks, schools or other places where children spend time.

- He tries to lure children into a van (often a white van), the woods or similarly isolated area with the promise of candy, money or other temptation.

- The clown is spotted primarily, sometimes exclusively, by children but remains unseen by police and other adults .

- Further investigation fails to uncover any photographic or other solid evidence, and the clown is never caught (or even proved to actually exist — that’s the “phantom” part).

Phantom Clowns have all the hallmarks of a good urban legend: a story of humor or horror (or both) that spreads from person to person, almost always reported as having happened to a “friend of a friend” (or FOAF) though the details may be fuzzy and the concrete evidence is sorely lacking. Urban legends are particularly contagious when they contain an implicit (or sometimes explicit) moral lesson, such as “never take candy from strangers” or “you can’t trust a man in a wig.”

Sightings of Phantom Clowns date back decades. The earliest sightings Coleman has discovered in his research occurred in Boston in 1981, with similar panics occurring in Cleveland and Kansas City around the same time, although there may be examples even further back. The most recent (before this year’s craze) occurred only two years ago, in 2014, in Indiana. An article in Slate playfully points out the many similarities between these Phantom Clown sightings and the portrayal of Pennywise the Clown in Stephen King’s popular novel, IT. Notably, however, the earliest of these sightings predate the publication of that novel, which came out in 1986 (and was adapted into a TV miniseries in 1990).

As it happens, a remake of IT is due out in theaters later this year, and Rob Zombie’s most recent crowd-funded film, 31 (which debuted in theaters last month) also features murderous clowns, as well as a group of traveling carnival workers. The coincidence of the Creepy Clown Epidemic with these movie releases initially sparked suspicions that the most recent stint of sightings was actually part of a marketing campaign by filmmakers.

Such suspicions aren’t entirely unfounded, especially considering that the very first “creepy clown” sighting in Wisconsin was eventually proven to be a bit of marketing. There’s a reason marketers today use “viral” marketing techniques that closely resemble many common characteristics of urban legends, in order to harness our natural tendency to relish a good story and pass it on to others.

However, the film production company has vigorously denied having any involvement. Stephen King himself even took to Twitter to express his concerns about the creepy clown reports:

Hey, guys, time to cool the clown hysteria–most of em are good, cheer up the kiddies, make people laugh.

— Stephen King (@StephenKing) October 3, 2016

And there’s good reason to take these denials at face value. Unlike viral marketing campaigns, which rely on carefully crafted social media memes and other clickbait designed to be easily and widely reshared, urban legends pass primarily by word-of-mouth and chain-letter style flyers and emails, rippling out through local communities with little to no concrete evidence to back them up. And that is exactly how rumors of creepy clowns began spreading through the American south in late August and early September.

Stories of these clown sightings were initially reported by the local media, with neither photographic evidence nor police confirmation that the alleged incidents had actually occurred.

But by mid-September, that began to change…

Stay tuned for Part Two, where we’ll explore the evolving nature of the Creepy Clown Epidemic and the psychology of creepiness.