As Asian Pacific American Heritage Month draws to a close, NbA Muslims and the Muslim Anti-racism Collaborative is featuring Sylvia Chan-Malik, who is one of many Asian American Muslims doing amazing things.

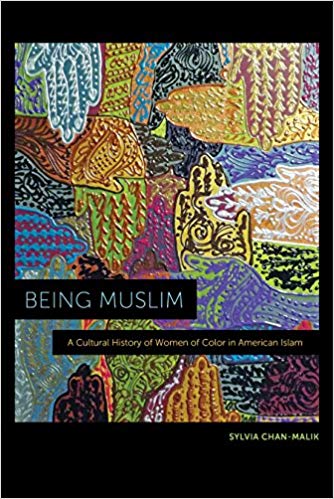

Sylvia Chan-Malik is Associate Professor in the Departments of American and Women’s and Gender Studies at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, where she directs the Social Justice Program and teaches courses on race and ethnicity in the United States, Islam in/and America, social justice movements, feminist methodologies, and multiethnic literature and culture in the U.S. She is the author of Being Muslim: A Cultural History of Women of Color in American Islam (NYU Press, 2018), which offers an alternative narrative of American Islam in the 20th-21st century that centers the lives, subjectivities, voice, and representations of women of color.

Her writings are also featured in numerous anthologies, including With Stones in Our Hands: Writings on Muslim, Racism, and Empire (UMinn Press, 2018), Routledge Handbook of Islam in the West(Routledge, 2015), and The Cambridge Companion to American Islam (Cambridge, 2013), and in scholarly journals, such as Amerasia, CUNY Forum, Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Religion, and The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. She speaks frequently on issues of U.S. Muslim politics and culture, Islam and gender, and racial and gender politics in the U.S., and her commentary has appeared in venues such as NPR, Slate News, The Intercept, Daily Beast, PRI, Huffington Post, Patheos, Religion News Service, and others. She holds a Ph.D. in Ethnic Studies from the University of California, Berkeley, and an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from Mills College.

We had an opportunity to ask Sylvia Chan-Malik about gender justice and arguments about feminism in American Muslim dialogues.

What is most frustrating to me about much of the “anti-feminist” discourse in US Muslim spaces is that those who proclaim to be “against” feminism utilize an extremely narrow definition of what “feminism” is. In general, the ideology they are against is that of the second-wave white feminist movement that arose out of the social and cultural struggles around gender in the late 1950s and 60s United States. This ideology was best captured by Betty Friedan’s book The Feminine Mystique, in which the author described the unhappiness and dissatisfaction of white, middle to upper-class American women, usually in the suburbs, who felt trapped in their domestic roles as wives and mothers. The book catalyzed the mainstream feminist cause in the US during the 1960s and 70s, for which primary goals were women’s economic parity with men, women’s individual freedom and autonomy, and reproductive rights.

What is most frustrating to me about much of the “anti-feminist” discourse in US Muslim spaces is that those who proclaim to be “against” feminism utilize an extremely narrow definition of what “feminism” is. In general, the ideology they are against is that of the second-wave white feminist movement that arose out of the social and cultural struggles around gender in the late 1950s and 60s United States. This ideology was best captured by Betty Friedan’s book The Feminine Mystique, in which the author described the unhappiness and dissatisfaction of white, middle to upper-class American women, usually in the suburbs, who felt trapped in their domestic roles as wives and mothers. The book catalyzed the mainstream feminist cause in the US during the 1960s and 70s, for which primary goals were women’s economic parity with men, women’s individual freedom and autonomy, and reproductive rights.

But that’s not all “feminism” is, all that the word signifies. As I argue in my book Being Muslim: A Cultural History of Women of Color in American Islam, women of color—namely Black women, but also Native, Latinx, and Asian American women—have long asserted visions of gender justice and women’s liberation that far exceed the ideologies of second wave white feminism, but which are part of “feminism’s” history in the United States So for example, in 1977, a group of women calling themselves Black feminists wrote the famous Combahee River Collective Statement, in which they articulated how they, as Black women, were sidelined in both the white feminist movement as well as the male-dominated and masculinist civil rights and Black Power movements. They defined Black feminism as a movement that sought collective liberation and centered the most marginalized in society. They connected their struggles as Black feminists to figures like Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Ida B. Wells, and Mary Church Terrell. Further, as the word has become commonplace term in our nation’s cultural lexicon, feminism has come to far exceed its second-wave meanings for subsequent generations, as many younger folks in my classes and otherwise they understand feminism through this popular definition: “Feminism is the radical notion that women are human beings.”

Second-wave feminism as political ideology or as I sometimes call it, “whiteness-invested feminism” is not an ally to Muslim women, in the US or elsewhere. It has been historically used to dehumanize Muslim women and otherize Islam, in many cases to justify war and occupation and to explain the “backwardness” of Islamic cultures. Yet that is just ONE subset of “feminism” and “feminist history” in the U.S. and beyond. So YES, I think having a conversation about feminism, and understanding what we are talking about when we are talking about feminism, and actually learning about histories of struggles for women’s rights in this country and all over the world, and then looking at what Islam says about women and gender, and rights—this can absolutely be a positive thing for Muslim women. The conversation around feminism, or women’s rights, or gender justice, or whatever we want to call it, could be so much richer, and far more productive in US Muslim communities and beyond if those engaging in it could be far less reactionary and presumptuous about what they think “feminism” is, and actually focus more on women’s issues, struggles, and desires in all their nuance and complexity.

In considering these issues, we must always remember that however one conceives of what “gender justice” is to them is extremely dependent on their own experiences. In the US, this has a great deal to do with race and class. An example I often give my students and audiences is that while white middle-class women in the 1960s and 70s saw getting jobs and going into the workplace as a means to freedom, as a “feminist” cause, Black women often did not agree with this goal, as they had been working all along, e.g. as domestics, factory workers, etc., and had long had no choice but to be the breadwinners in their families. For Black working-class women, “freedom” or “liberation” didn’t mean going to work, it meant being to stay home with their own husbands, children, and families.

US Muslim women, who are made up of folks from extremely diverse racial, ethnic, regional, class, and linguistic backgrounds not only have to find ways of talking across such differences but also in regards to how they might differently view notions of gender justice or women’s rights.

The trick is to understand that what we consider “freedom,’ “justice,” or “feminism” is deeply shaped by our racial and class identity. Historically in the US, the vast majority of Muslim women, especially prior to the 1970s, have been Black American Muslim women. Thus, as I argue in my book, it is critical for Muslim women in the contemporary US, whether they are South Asian, Arab, Latinx, white converts, to recognize the historical legacies and contributions of Black Muslim women, and realize that women’s liberation and gender justice—whether you call it feminism or not—has always been a part of the story of US Muslim women. To engage, study, grapple with, and discuss “feminism”—and all the histories and legacies that terms signify— is a crucial component of figuring out what it means to be a US Muslim woman in the 21st century United States. We must strive to collectively craft a narrative of U.S. Muslim women’s lives that fully embraces and acknowledges the contributions of Black Muslim women and their commitments to gender justice, and consider how their histories and legacies may light a path forward.