Gerald R. McDermott

Lutheran CORE Conference, Columbus OH

August 10-11, 2011

Several weeks ago two rising seniors came to my office. One is at the Naval Academy, and the other at one of the big public universities in Virginia. Both had taken religious studies courses that suggested Jesus is just one of many saviors in the history of the religions, no better than any other. And that they would be arrogant to think that Jesus is superior to the Buddha or Allah.

These two young men were troubled, for they had been raised in Christian churches and now wondered if they had been duped by pastors too limited in knowledge to realize that, as their professors seemed to suggest, all the world religions are teaching pretty much the same thing. In the course of our hour together, I tried to explain to them that while there are similarities between the moral teachings of the Christian church on the one hand, and the basic moral principles of most of the great world religions on the other, the person of Jesus Christ is stunningly unique in the history of religions. No other so-called savior, for example, died and rose again to bring sinners into communion with the Triune God.

These young men have been indoctrinated in what religious studies folks call “religious pluralism.” This is not simply the observation that there are many religions but it is a religion in and of itself. Smuggled between the lines of lectures and texts is the religious proposition that all the great world religions are roughly equal in their truths and mistakes, and that even if postmoderns think some are slightly better than others, it is narrow-minded to believe that one is vastly superior to the others. And idiotic to think that there is any sort of objective truth that cannot be dissolved into the subjective preferences of class, race, gender and power.

I.

How in the world did our Western world get to this way of thinking? It is a complicated story, of course, but this kind of “religious pluralism” goes back in part to ways of thinking crystallized by British philosopher John Hick, whose book God Has Many Names (1980) has had enormous impact on the last two generations of westerners trying to figure out who or what is god.

Several times in this book Hick makes explicit a basic assumption that is at the heart of religious pluralism—that there is a basic sameness at the heart of all the world religions. From this assumption Hick and other pluralists conclude that Christian missions are both unnecessary and immoral. Hick tells how as a young man he explored the world religions by visiting mosques and synagogues and temples. Then he states his conclusion, which became a presumption undergirding all of his thought about the religions: “It was evident to me that essentially the same kind of thing is taking place in them as in a Christian church—namely, human beings opening their minds to a higher divine Reality, known as personal and good and as demanding righteousness and love between man and man.”

Therefore (pluralists reason) if Buddhists and Hindus and Muslims are really worshiping the same god we are, and if only our name for this god is different, and if all of our other conceptual differences about the divine are not as important as these characteristics which Hick has just stated, then there is no need for us to preach our version of the divine to others.

For they already have it.

In fact, it is arrogant and immoral to insist on our name for God—Jesus Christ—when our name is only a product of our culture. We have put a local, cultural stamp on what is in fact universal and beyond culture.

Even worse, they say, we Christians presume that without personal union with this Triune God, people are lost—even those who are convinced they have the divine, but under other names.

This Christian particularism is obviously mistaken for Hick because he considers it obvious that “all God’s creatures . . . [will find] ultimate salvation.”

How does he know that? He doesn’t say. He assumes it, without giving reasons for saying so. Yet he and other religious pluralists condemn Christians who talk about final judgment and lostness, and who do give reasons for saying so. They condemn all other religions that suggest their way is the best way to the divine. Yet this is what every religion proclaims.

Now pluralists insist on the need for tolerance of other religions. But is this tolerant? To declare dogmatically that it is not possible for one religion to have a unique way to God? And that therefore every religion that makes this claim is wrong? Since every religion in fact does make this claim, pluralists maintain that every world religion is wrong.

Even the Dalai Lama makes such a claim. Gavin D’Costa has shown that while he tells the world there is no need for conversion to another religion because every religion gets you to the divine, the Dalai Lama tells insiders that the best way to spiritual ultimacy is by Tibetan Buddhism, and that the best of the best ways is his dGe lugs school of Tibetan Buddhism. Pluralists would say this must be wrong because no human conception of ultimacy can possibly be final.

Pluralism therefore is intolerant. It is also narrow-minded. For it fundamentally opposes any claim to absolute truth. Instead it insists that every religious claim is relativized by, and reduced to, the historical conditions that produced it. It cannot affirm the validity of those who take a non-pluralist and non-relativistic view. I will argue in a few minutes that historic Christian orthodoxy affirms the existence of partial truth—both moral and religious—in other world religions. So we can and should be open to partial truths among those who disagree with us. But hard-core pluralists cannot affirm partial truth among those who disagree with them. They cannot accept any particular claims to ultimacy by Christian faith or any other faith.

For pluralists, when it comes to religion there are no absolutes. But of course when they say that, they have just stated a religious absolute. Perhaps they should say, “There are no absolutes, except the one I just stated.”

We should also recognize that pluralism must lead to agnosticism. For if all we have is our “finger pointing at the moon,” as pluralists tend to say, then reality can never be expressed in anything we say or imagine in human or earthly form. (To say that this is at odds with belief in the Incarnation is a gross understatement.) If the Father of Jesus Christ and Allah and Kali and the Aztec god who demanded human sacrifice are all really the same God, then this God recedes into a realm that is utterly unknowable. John Hick’s pluralism therefore leads to skepticism and agnosticism. If he is right, no one knows God. All the religions, taken together, fail to bring us to the knowledge of God and actually keep us from the knowledge of reality.

But what if the basic presupposition of pluralists is faulty? What if religious pluralists like Hick who say that all the world religions are doing pretty much the same thing–worshiping a good and personal god—are actually mistaken?

When we look carefully at what the world religions actually do say, we find very different things. For example, the Buddha himself was agnostic about the existence of a personal god, and the school of Buddhism that is closest to his teachings–Theravada—denies the existence of god and persons! Philosophical Hinduism and Daoism say the same—that there is no god. They also say there are no final distinctions, for all is one, and therefore there are no persons at all. This means that finally, in ultimate reality, there is no distinction between you and your chair. Your mind and will and personality are ultimately unreal. The only thing that is finally real is the great impersonal Oneness called Brahman or Dao.

Toto, I have a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.

The world religions are not doing “pretty much the same thing.” On the most basic questions—such as whether there is a god and whether individuals are real—there is profound disagreement. As we have seen, some believe in a god or gods, and some say there are no gods at all! Some believe reality is made up of things and persons, and others say there are no such things! Even the ones that believe in a personal god have drastically different views of that god, and how to reach him or her.

You have heard it said that the world religions are simply different paths up different sides of the same mountain, with all of them reaching the top or goal. The reality is that the goals of the world religions are light-years from the Christians’ goal, which is union as individuals in love and joy with the three persons of the Trinity, and in union with one another in a beloved community. Each of the world religions is its own mountain, and each peak is very different and far away from the others.

Yet pluralists still say all the world religions are doing “pretty much the same thing.” Which means they are not really pluralistic. They say they believe in many goals but actually believe in only one—“reality-centeredness” for John Hick, liberation from social oppression for Paul Knitter, or universal faith and rationality for Wilfred Cantwell Smith. Pluralists believe religion is like toothpaste: brand differences are inconsequential because they all have the same function and end. In effect, then, pluralists deny any pluralism of real consequence.

II.

Despite this incoherence, pluralism has made its way into Christian churches. Long before John Hick gave it formal expression, its loss of faith in Christian particularity—the saving person of Jesus Christ–was being felt in changing conceptions of mission. W.E. Hocking’s Re-Thinking Missions (1933) redefined the goal of mission as “preparation for world unity in civilization.” Civilization, which has sometimes been a by-product of the gospel and always is challenged by the gospel, was now to be the focus of mission rather than the gospel itself. In the 1960s some in the World Council of Churches (WCC) claimed that “the world sets the agenda for the church”—that is, that God guides the church not through scripture or church tradition but through secular trends. A key turning point was the WCC’s 1968 assembly at Uppsala, Sweden, where it was said that the church’s goal ought to be “humanization” rather than “salvation.” It was at that meeting that what WCC general secretary Konrad Raiser called “Christocentric universalism” was replaced by a Trinitarian paradigm in which the Bride coming down from heaven was not the ecclesia but the oikumene—not the church of Jesus Christ but the family of nations participating in democracy. Then in the 1972-73 Bangkok meetings of the WCC’s Commission on World Mission and Evangelism came a proposal from ecumenical leaders for a moratorium on missions.

Today in many Protestant mainline churches “missions” means building homes for the poor. That is a noble and Christian project, and sometimes ought to be a part of mission, but it is not what the apostles meant by mission, and certainly not what Jesus meant when he commanded his followers to make disciples in every nation, baptizing in the name of the Father, Son and Spirit, and teaching them everything that he had commanded them (Matt 28.18-20).

Last year Professor Paul Martinson, speaking at this conference, quoted an ELCA missionary who said the ELCA “is officially allergic to the idea that the primary purpose of our mission work is to proclaim the gospel to the non-Christian, so that they will become Christian.” Prof. Martinson cited the missiologist Jim Scherer’s chilling observation: “The Great Commission . . . is dismissed as a symbol of the past. . . . [We now live in a day of] conversionless Christianity [in which we are] to make common cause with other religions in a common search for truth.” (211-12)

III.

Is there really a common search for truth? Yes and no. Yes in the sense that many–if not all–search for a truth beyond themselves. And there are common questions among thinkers from different cultures and religious backgrounds—such as whether we can know that there is more to reality than atoms and molecules, and what it means to be morally good. As we will see, there is some commonality between Christian moral theology and what is taught morally by other religions.

We can also say that other religions teach some religious truth.

For example, Islam is right when it professes that God is one and not many, and greater than anything we can imagine. Jews speak truly when they confess that God is holy and demands conformity to His moral law. Pure Land Buddhists and bhakti Hindus teach truly when they explain that salvation comes not by human effort but divine grace. Their understanding of grace is fundamentally different from ours, but when they say that forgiveness comes by divine action and not human action, we have to say they are on to something.

We can also say that other religions teach similar moral principles. We agree, for instance, with Confucius’ Silver Rule, “Don’t do anything you don’t want done to you.” We affirm the Buddha’s precepts forbidding lying, stealing, murder and sexual sin. We can see the basics of the Ten Commandments echoed in the Qur’an.

At the same time, however, we have to say that Jesus Christ is absolutely singular. No other religious founder claimed to be God in the flesh (even Hindus concede their avatars only appear to be human). While the Buddha stated that he was no more than a man and said that we must be lamps unto ourselves, Jesus said that to see Him was to see God, and that He is the light of the world.

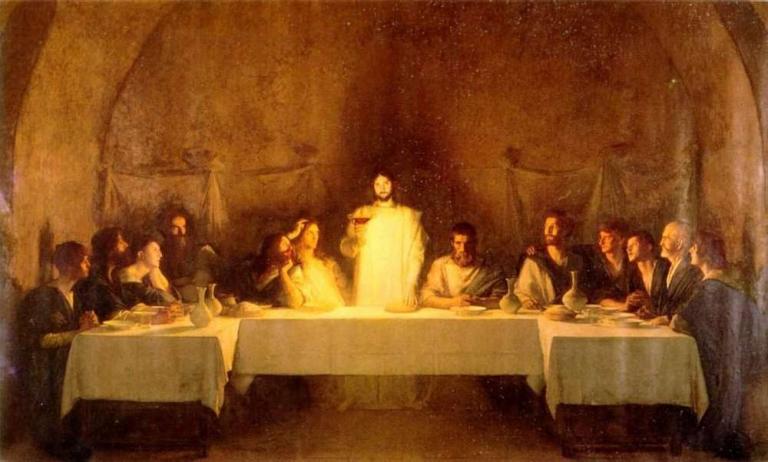

The Christian church’s central claim, that the crucified Jesus rose from the dead, is unparalleled in the world religions. Though it is not something that can be proven to a skeptic by historical research, we have the testimony of his followers that they thrust their fingers into the holes in the body of the risen Christ and shared with him a breakfast of fish and bread. Neither ghosts nor hallucinations eat fish and bread.

No other religious founder came even close to promising salvation from sin, death, and the devil by a crucified God who draws believers up into the life of a triune community of divine love.

Jesus also gives unique answers to the problem of pain. The Buddha taught his followers to escape suffering, whereas Jesus showed the way to conquer suffering by embracing it. This is why Buddhists look to a smiling Buddha seated on a lotus blossom while Christians worship a suffering Jesus nailed to a cross.

The Dao De Ching is the Bible of philosophical Daoists and many postmoderns. It portrays Ultimate Reality as an Impersonal Something requiring resignation and accomodation to minimize or perhaps escape suffering. In contrast, Jesus said Ultimate Reality is a Person Who took up suffering into Himself. So the Christian God does not stand at a distance while we suffer but comes down and enters into our suffering with us. In fact, God Himself suffered the ultimate evil of death and somehow overcame it, and promises to take us up into that victory.

Muslims rightly believe that God is great. The Christian story of Jesus, however, reveals two kinds of greatness. One is illustrated by the emperor who sits high on his luxurious throne, far removed from the daily cares and pains of his subjects. He is surrounded by servants who see that his will is obeyed throughout his kingdom.

But there is also the greatness of a brilliant student who comes to the university and works hard to study medicine. After graduating, he does not set up a lucrative practice among the wealthy, but goes among the country’s poorest people to heal them. This is what God in Jesus Christ did. He revealed His greatness by stooping to save.

Finally, Jesus unveils an unparalleled intimacy with God. The Qur’an relates that God is closer to us than our jugular vein, but it never calls God “Father.” Jesus, on the other hand, addressed God as “Daddy” (a translation of the Aramaic “Abba”), and promised that He would lift believers up into that same intimacy.

IV.

So Jesus is unique. But is He also for everyone universally? Some say he cannot be in this age of unparalleled religious diversity. They claim that we have an abundance of different religions which the world has never known before.

That’s really not true. The early church faced a dizzying array of cults and religions competing with its proclamation that Jesus was Lord. Third-century Rome and Alexandria were filled with sorcerers, magicians, philosophers from East and West, astrologers, Gnostics, Christians, and Jews. These cities were as religiously pluralistic as New York City and Hong Kong today. Theologians such as Justin Martyr, Clement of Alexandria, Irenaeus, and Origen developed sophisticated theologies of the religions as sensitive and often better than Christian theologies of the religions today. (See God’s Rivals).

And it was in this religiously pluralistic world of the first three centuries that the church proclaimed that Jesus Christ is for everyone: “Christ Jesus gave himself as a ransom for all” (1 Tim 2.6); “Jesus tasted death for everyone” (Heb 2.9); “He is a propitiation for our sins, and not for ours only, but also for the sins of the whole world” (1 John 2.2).

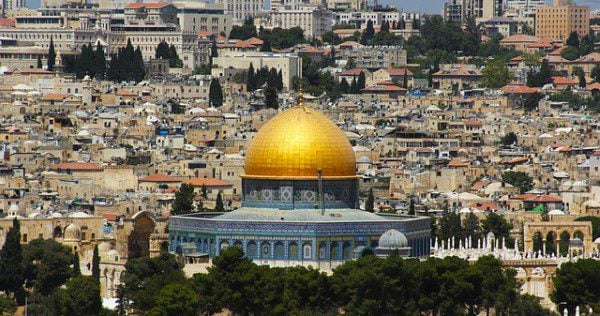

If this seems strange to many today, it was stranger still in the ancient world. There and then, people believed there were many gods, and that each was a savior of his or her own tribe. But first the Jews came to say that their God had created the whole world and all its peoples and tribes. Then the Christians came saying that Jesus had come to redeem the whole world. This struck many first-century hearers as incomprehensible. The God of one tribe was interested in the people of all tribes. This God wanted to free them from the prisons of class and race and even religion by saving them from sin, death and the devil.

Jesus himself taught that he was the universal savior—for every culture and nation. He said in Mark 13.10 that before the end the gospel “must be preached to every nation.” In Him was realized the purpose for calling Israel in the first place, which was to bless every nation, as God told Abraham in Genesis 12. Now this promise was being fulfilled through the mission of the church. The blessings of Abraham were being shared with all the nations through Abraham’s offspring—the perfect Israelite—Jesus Christ. He was reaching the nations through his body, the church.

Peter figured this out. He told the Jews at Solomon’s Portico: “You are the sons of the prophets and of the covenant that God made with your fathers, saying to Abraham, ‘And in your offspring shall all the families of the earth be blessed.’ God, having raised up [Jesus Christ], sent him to you first, to bless you by turning every one of you free from your wickedness.” (Ac 3.25-26)

In this story from Acts of Peter and Luke we see the biblical pattern: God would bless the world (the universal) through the particular (Israel and her embodiment in the perfect Israelite Jesus Christ).

Luke makes it clear that Jesus Christ has come for every culture because every culture and person needs to be redeemed by this perfect Israelite. The gospel moves from Jerusalem Jews to Samaritans (Ac 8), to a proselyte Gentile (the Ethiopian eunuch in Ac 8), to a God-fearing Gentile (Cornelius in Ac 10-11), to the real Gentile world of Greeks and other cultural groups in Antioch and Asia Minor and Greece and (finally) Rome (Ac 11-28).

With an eye to the Genesis 10-11 account of the founding of the 70 nations of the world by descendants of Noah’s three sons, Luke intimates that the gospel has reached all the nations descended from those three sons by telling the story of the gospel going into Africa through the Ethiopian eunuch (the land of Ham), starting in Israel and Egypt (the land of Shem), and progressing through Paul north and west to Asia Minor and Athens and Rome (lands of Japheth). (CH Wright, ch 15)

Jesus is universal. He is for every person and every culture. For he alone is the light of the world, the truest and fullest truth, the most abundant life, and the only way to the Father. Nowhere else but in his church is the story of the incarnate God who died for our sins and was raised for our justification. Nowhere else is this way provided to life in the Trinity.

V.

What are the implications of the uniqueness and universality of Jesus Christ?

The first is that we must reject universalism—not the universal claims of Christ which we have just discussed but the old heresy technically known as apokatastasis and revived recently by the pseudo-evangelical Rob Bell and plastered across the cover of Time magazine this spring (“What if there is no hell?” April 25) —that teaches that everyone will eventually be saved. It is no coincidence that this has been moving through Protestant mainline seminaries and ministries for some decades, at the same time that missions have been transformed from sharing the gospel with non-Christians to building houses and other kinds of social work—rather than seeing both as going hand in hand. For decades now, the idea of telling the story of the crucified God who died to save sinners has seemed unnecessary. For if everyone will eventually be saved, why go to the trouble of telling them something new and different and possibly offensive?

We must reject universalism because our Lord rejected it. He spoke insistently of those whom he would tell, “I never knew you; depart from me, you workers of lawlessness,” of weeping and gnashing of teeth, of a sin that would never be forgiven either in this age or the age to come, of people being thrown into the outer darkness, of being sentenced to hell, and of people going away into eternal punishment. Jesus and his apostles preached about the real danger of being lost forever (Matt 7.21-23; Matt 8.12, 24.51; Lk 13.28; Matt 12.32, 8.12; Mk 9.43-48; Matt 25.46).

Ironically, for universalists hell and damnation are a moral problem; but for Jesus and the apostles, damnation in hell resolved a moral problem. The problem was the question of whether and when God would finally punish the wicked. Hell was a central answer to the question of theodicy.

The universal church considered universalism in 533 and condemned it at the Council of Constantinople. Affirmations of the eternal punishment of the wicked appear in the Athanasian Creed (early sixth century), the Fourth Lateran Council, Canon 1 (1215 A.D.), the Augsburg Confession, ch. 17 (1530 A.D.), the Second Helvetic Confession, ch. 26 (1564 A.D.), the Dordrecht Confession, art. 18 (1632 A.D.), and the Westminster Confession, ch. 33 (1646)—as well as many later denominational statements of faith from the 1600s onward. As Richard Bauckham has shown, there were virtually no major Christian thinkers who taught universalism prior to the nineteenth century, and before Origen (c.185-c.254), who seems to have imported the universalism attributed to him from the Gnostics he was battling, there is no evidence of universalist belief among the churches in their first two centuries.

In the twentieth century CS Lewis took up the subject in his delightful allegory on eschatology, The Great Divorce. In chapter 13 he puts into the mouth of George Macdonald (1824-1905), the Scottish author and poet who taught universalism, a rejection of universalism. This is surprising at first, because Lewis was deeply influenced by Macdonald’s books and even called Macdonald his “master.” But in The Great Divorce, after the narrator finds Macdonald in heaven and reminds him that he had been a universalist while on earth, Macdonald has changed his mind. The problem with universalism, Lewis’ Macdonald now advises, is that it removes “freedom, which is the deeper truth of the two.” The other truth of the two is predestination, “which shows (truly enough) that external reality is not waiting for a future in which to be real.” Lewis’ Macdonald was saying that universalism rejects the deep truth that there will always be some who want nothing to do with a God who invites them to confess their sins, serve persons other than themselves, and worship Someone other than themselves. As Milton put it, “The choice of every lost soul can be expressed in the words, ‘Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.’”

The other implication of the universality of Jesus Christ is that we should engage in mission as disciples of Jesus Christ—which means, among other things, sharing the good news of the gospel with those who do not have it—including those of other religions.

Liberal Christians protest that people of other religions are already saved in their own ways. But the New Testament makes it very clear that union with the Trinity comes only by Jesus Christ. Jesus said, “No man comes to the Father except through me” (John 14:6). Peter declared, “There is salvation in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven by which we must be saved” (Ac 4:12) John announced, “God has given us eternal life, and this life is in his son. He who has the Son has the life; he who does not have the Son of God does not have the life” (1 John 5:12).

The apostles were clear: there is no other savior, and no other way to God but by Jesus. There is no salvation through other religions. There is no way to the true God except by knowing Jesus Christ. No other faith but the faith of Jesus and the apostles tells the true story about how sinners are reconciled to a holy God.

The apostles had a sense of urgency about evangelism and missions that is strangely absent in much of the church today. One reason few today have this urgency is because of the way damnation has been taught by some to be the arbitrary decision of God before time to send millions to hell. Another reason is that many have been put off by the overly-literal way in which biblical language about hell has been interpreted. A third factor has been the spread of universalism. In any event, the apostles believed in the reality of eternal lostness in a way that many of us do not. Paul wrote to the Corinthians that “the unrighteous will not inherit the Kingdom of God” (1 Cor. 6.9). The John who wrote Revelation testified that “if anyone’s name was not found written in the book of life, he was thrown into the lake of fire” (Rev 20.5). It was this utter conviction that without Christ some will be finally and forever lost that gave courage and urgency to thousands of Lutheran missionaries who brought the gospel to Africa, China and Latin America. They knew they were not only offering their hearers all the benefits of eternal life with Christ in this life but also showing sinners the way to escape eternal lostness.

Now some theologians in the early church thought some—not all–people in other religions might be saved eventually, but it would be in spite of their religions, not because of them. And it would be only through the life and death of Jesus Christ, and by accepting the gospel in some way and time God only knows—at the point of death, or in the millennium, or some other way symbolized by Christ’s descent to the dead. In other words, they would have to recognize that their religions were not the way to the fullness of God, but that Jesus Christ is in a different category altogether. That he is not simply another savior in another religion, but God in the flesh with a promise heard from no one else—forgiveness of sins and eternal life through a God both crucified and raised from the dead.

So we should not refrain from evangelizing a person of another faith because we think that religion will get her to God. It will never get her to the triune God. She needs to hear the good news of Jesus. This alone will get her all the way to the true God.

Jesus himself told all of us who follow him to “make disciples of all nations” (Matt 28:18-20). This is a command which he repeated several times (Mark 13:10, 16:15; Ac 1:8).

There are other Christians who protest that some non-Christians have so much truth already. True enough. But they still don’t know the Savior. Part of the truth is a far cry from knowing Truth incarnate. If we know that people in a village are slowly dying from impure water that is nevertheless keeping them alive for some years, we won’t be satisfied that they have water and are still alive. We will want to get them pure water to stop the dying process. The same is true in matters of faith. We will want everyone, even those who have some water, to get the pure Water of Life that brings wholeness in this life and salvation in the one to come. Lydia in Philippi was already worshipping God, but Paul made sure she heard and accepted the gospel so that she might know the true God in all his fullness—Jesus Christ (Ac 16:14).

Now by evangelism and mission I don’t mean proselytizing, which is often coercive, rude, and un-listening. No, true evangelism is when we take the time to make a lasting friendship, listen to our friend’s perspective, offer loving help where it is needed, and humbly and respectfully share the gospel when the Spirit opens the door—not before.

I say “humbly” because we may trust we have the Truth in Jesus but we must acknowledge that we see him only in part and follow him imperfectly. Having Jesus is not the same as knowing him in full or following him fully.

I say “respectfully” because we should talk with our non-Christian friend after we have studied his religion, seen what truth is there, and tried to represent it fairly. Of course, every truth in another religion will be essentially different from the Christian version that is centered in Jesus Christ. For example, Muslims also affirm a personal God. But Allah is monumentally less personal and more distant from the Father of Jesus Christ, whom Jesus called “abba,” a term of great intimacy. So where other religions agree with biblical truth, they share only partial truths. Yet they are partial truths.

Once more we observe that it is Christians who believe in the uniqueness and universality of Jesus Christ who are able to recognize truths in other religions. Pluralists who deny Jesus’ uniqueness and universality also deny ultimate truths in every other religion. It is Christian orthodoxy that is truly pluralist, and the theology of pluralism that is not.

Now I have been talking just now about personal evangelism. It is critical for the growth of any church. Recent studies of mega-churches have shown that one of the reasons—not the only reason, for there are also Christian migrations–why they are “mega” is because the average member invites people to church far more often than the average member of First Lutheran, or your typical small or mid-sized church.

But as church leaders we need to teach our people not only to share their faith one-on-one, but also to support church missions. Today we hear about the explosive growth of Christianity in the Global South. The new center of gravity for Christianity is in the southern hemisphere. In 1900 eighty percent of the world’s Christians lived in Europe and North America; today seventy percent of the world’s Christians live in the Global South. In 1900 the average Christian was white, relatively prosperous, and lived in the northern hemisphere. Today the average Christian is brown, female, and poor, and lives in places like Sao Paulo, Brazil and Lagos, Nigeria.

How did this dramatic transformation of world Christianity take place? It started at the end of the eighteenth century and proceeded furiously throughout the nineteenth century, and on into the twentieth century. European and American churches sent thousands and thousands of missionaries to China and Korea and Africa and Latin America, determined to fulfill the Great Commission in their lifetimes. Some of you are the children or grandchildren of those heroic missionaries. These saints built schools and hospitals and taught people how to get better crops. But the main reason they came was to share the gospel of Jesus Christ, who was unlike any other god and had come to offer eternal life to every human being. The result was what the great church historian Kenneth Scott Latourette called the “greatest expansion of Christianity” in its history. Latourette died before he could learn of the expansion of the expansion—the unparalleled growth of the churches in the Global South in the 20th century. Now there is even a reverse movement, from South to North. Missionaries are taking the gospel from Africa and China and Brazil to such new wastelands as New York, Seattle and London.

We all know that much of the Protestant missionary movement in the 19th century was assisted by the colonialist attempts of European governments to exploit what used to be called Third World countries. We also know they didn’t always distinguish the gospel from their own cultures. We should learn from these mistakes and work hard to distinguish Christ and the gospel from our own cultural baggage. But we should also know what Yale historian Lamin Sanneh has written. The son of a Muslim tribal chief and mullah in Gambia, Sanneh started searching for Christ after reading about Jesus in the Qur’an and then was led to conversion by conversations with Christian ministers! Sanneh has observed that historians of the 19th-century missionary movement failed to distinguish between gospel transmission by missionaries and what he calls “indigenous assimilation.” By that he means missionaries empowered Africans to adapt and apply the gospel to their local contexts, often in surprising ways. Sanneh says this was especially at work in the Bible translation movement, which “imbued the local culture with eternal significance” in ways the missionaries never imagined. “In other words, the missionaries set into motion a process of religious change in which the Africans themselves became the key players.” The gospel not only used their cultures to show Christ in new ways, but also preserved the best parts of those cultures.

Lutherans today have a unique opportunity in a world needing the gospel like never before. When pluralists say you can come to God without Jesus Christ, and you can have the Spirit without Jesus Christ, or the Christ without Jesus, Lutherans can remind the church of Luther’s special insight that the true God is Trinity who therefore cannot be found apart from the gospel story of Jesus the God-man who died for the world’s sins and was raised for sinners’ justification. Lutherans should remind themselves and others of their doctrine of the communion of attributes, which means in this context that you cannot have the Spirit without the person and work of Jesus Christ, and there is no Christ apart from the cross and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth. At a time when these dogmatic issues about the person and work of Jesus Christ are leading all of Protestantism around the world to a fundamental realignment, Lutherans have the opportunity to lead the orthodox side of the realignment, putting missions on the true foundation of the god-man Jesus Christ whose humanity and divinity are never separated.

So let us dedicate ourselves and our churches to form new mission societies in the new Lutheran churches!! Prof. Martinson last year told us of Lutherans in recent decades who said Never Again! to the work of biblical missions. Let us now say as Lutherans, Never again shall we ignore our Lord’s call to bring his name to all the nations!! Never again shall we be embarrassed to proclaim that Jesus Christ is the Way, the Truth and the Life, and that no one comes to the Father except through Him.

Let us once more teach our children that one of the ways to be a hero is to share the gospel with a people group that has never heard what CS Lewis called the only myth that is historically true—the biblical account of the true God who died and rose for us. Let us teach our churches once more that there are still hundreds of people groups that have not heard the gospel, especially in the Muslim world but also right here in Columbus and countless communities across this land. Let us teach and lead our churches to support mission works and individual missionaries who make deep sacrifices to “make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that Jesus has commanded them.” (Matt 28.18-19)

We have faith today and a place in the Kingdom today only because Lutherans before us were faithful to the Great Commission. Let us do the same for the next generation. Let us be faithful to Our Lord’s command. Let CORE and the NALC today take it as their mandate to play their Holy Spirit-directed role in the mission to the nations.

VI.

In conclusion, orthodox Christians should not be afraid to say there is truth in other religions. There are moral truths that we can affirm—and even some limited theological truths. There are certain moral projects—such as the fight for the rights of the unborn and elderly and for the family and the poor—that we should join with other religionists as co-belligerents and friends at work for the common good.

But at the same time we should not be bashful about proclaiming the absolute uniqueness and universality of Jesus Christ. As John proclaimed in his vision of the Apocalypse, only the “Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, the Lamb standing as though it had been slain,” was “worthy to open the scroll written within and on the back, sealed with seven seals.” No one else “in heaven or on earth or under the earth was able to open the scroll.” He alone was worthy because he alone “was slain, and by [his] blood [he] ransomed a people for God from every tribe and language and people and nation, and made them a kingdom and priests to our God” (Rev 5.1,3,5, 9-10). Jesus Christ is universally true for every culture and people precisely because he is unique. He and He alone “has conquered” sin, death and the devil. For this very reason he alone is able to provide salvation for all.