Gerald R. McDermott

Roanoke College

In an article in the current issue of First Things (http://www.firstthings.com/article/2013/12/evangelical-retreat), Russell Moore argues eloquently for the best sort of Evangelicalism—that which recognizes the need to think with the Great Tradition as it reads the Bible, holds on faithfully to dogmatic and moral orthodoxy, and does not shrink from going public when the culture attacks the gospel on issues such as sanctity of life, religious freedom, and the meaning of sex and marriage. It rolls up its sleeves to run adoption agencies, soup kitchens, and halfway houses for released prisoners.

But I wish he had stuck to the exhortatory and optative rather than speaking so often in the indicative. In other words, when he speaks of “the center of American Evangelicalism” and what “the new kind of Evangelical church” does, he suggests that the majority of younger Evangelicals and their churches have 45-minute Calvinist sermons, strict membership requirements, and hymns with Puritan lyrics.

This is no doubt true of the Reformed branch of the Southern Baptist Convention, where he is situated. But there are more Arminian Evangelicals than Reformed, and there are tens of millions of charismatic and Pentecostal Evangelicals whose churches would gag on Calvinist lyrics—even if the number of Reformed charismatics is rising because of the popularity of Wayne Grudem’s Systematic Theology. Thankfully, many non-Reformed are also holding fast to the same vision and practice which Moore proposes.

But the Evangelical world is not as solidly orthodox as Moore suggests. It is not just “the professional dissidents who make a living marketing mainline Protestant shibboleths to Evangelical college audiences.” The students who listen to them are often persuaded. They write books which convince many. Michael Brown’s new book Hyper-Grace shows the rising tide of antinomianism in charismatic circles using a radical grace message similar to that taught in mainline Protestant revisionist churches: Christ has done it all, hence talk of morality or eternal hell is false legalism. In the last fifteen years more books have been published by Evangelicals recommending universal salvation than warning against it. Most Evangelicals know of friends who have departed the fold because the cultural tsunami of support for gay marriage has made them question the Church’s moral authority. A March 2013 PRRI/Brookings poll shows slippage: while only 15% of white evangelical seniors support gay marriage, 51% of white evangelicals under 35 do.

Not all Evangelicals are Great Tradition Evangelicals. While the two greatest minds at the headwaters of evangelicalism—Jonathan Edwards and John Wesley—were guided by the Great Tradition, many other Evangelicals have followed the “no creed but the Bible” hermeneutic. Evangelical pastors in this stream will sometimes tell their auditors, “Don’t believe what I am telling you on my authority; go home and read the Bible for yourself and make up your own mind.” The final authority then becomes the autonomous ego, and all traditions on principle are rejected. If the individual reader of the Bible reaches a conclusion different from the Great Tradition, so much the worse for the Great Tradition. And if spiritual experience is considered more important than doctrine—as is often taught in contemporary Evangelical churches—then tradition matters even less, even Evangelical tradition.

This is not a disagreement between low church and high church, or between Baptists and Anglicans. For Baptists have their own theological tradition rooted in the Reformation tradition, as Timothy George and David Dockery have shown.

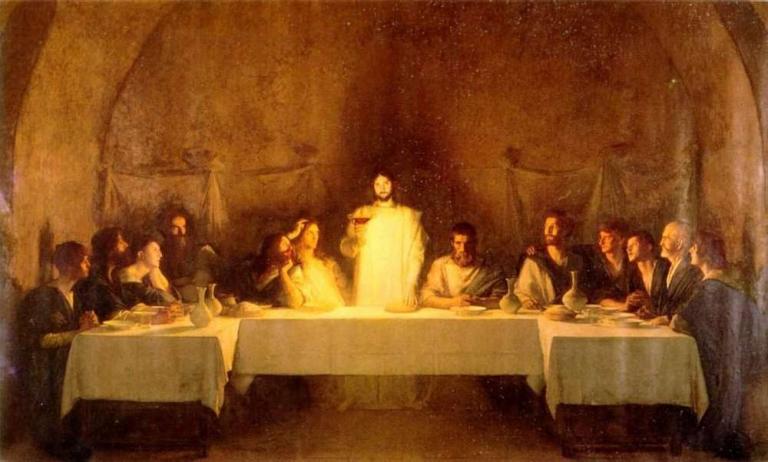

I agree with Moore that Evangelicals and Catholics can learn from each other. While Catholics can learn much from the historic Evangelical imperative to mission (the Pope’s new apostolic exhortation notwithstanding) and its practice of church discipline, Evangelicals need to learn from Catholics that true faith cannot be reduced to subjective experience or even the knowledge that Jesus died for my sins. Instead it is a “thick” world of mutually reinforcing dimensions–seeing the beauty of God in Christ, as taught in Scripture, summarized by the creeds, enacted in liturgy, developed by the great theologians, displayed in the saints (Evangelicals should think here of their “heroes of faith”), and beheld in icons.