The other day a shocking thing occurred.

At a rally to support persecuted Christians–called by the new group “In Defense of Christians”–Senator Ted Cruz was booed off the stage when he declared that Christians have no greater ally than the nation of Israel.

The group is spearheaded by Catholics and Eastern Orthodox Christians, who have many Arab Christian brothers and sisters in the Middle East who are under siege.

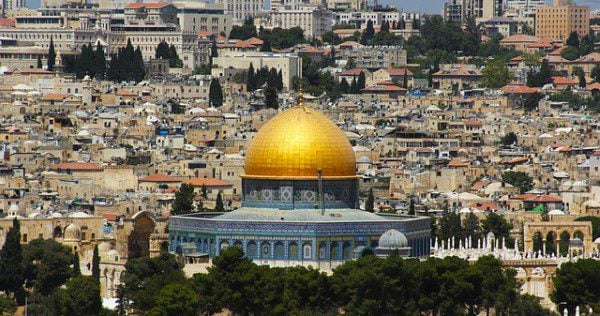

Obviously the Christians who booed Cruz think Israel is an enemy of their Arab Christian friends—despite the fact that there is more religious freedom for Christians in Israel than in any other country in the Middle East. And it is not only religious freedom, but quality of life and economic opportunity that are better for Palestinians in Israel proper than in Egypt or Syria or Lebanon. Not to mention Iraq, where Christians are being murdered by ISIS and other Islamist groups.

I imagine the Christians who booed Cruz think Israel stole the land from the Palestinians in 1948, and control the West Bank in violation of international law. Both of these claims are highly contested, and generally not sustainable. These Christians would say that today’s land of Israel is no different from the land of, say, Turkey. It is full of Christian history, but has no special future according to biblical prophecy. For, according to this view, the biblical covenant that God promised to Abraham and his progeny was transferred to the Church in 30 AD when Jesus rose from the dead. The covenant with the Jews has been superseded by the new covenant with the Christian church.

This has been the majority opinion of Christians since the second or third centuries. It is called “supersessionism” or “replacement theology.” A corollary of this is that the land of Israel no longer has theological significance for Christians, since in the New Testament the promises pointing to the future are about the whole earth and not the particular land of Israel.

I am not so sure.

I think there are many passages in the NT that point to a future for Israel as a distinct land within the renewed earth. Such as Paul’s statement in Romans 11 that God’s election of Israel is “irrevocable” (v. 29), when all Jews associated that calling with a land; the expectation of Mary and Zechariah that God would save Israel from her enemies (Luke 1:54-55, 68-71); and the book of Revelation’s seeing a future for the twelve tribes of Israel and the city of Jerusalem (7:1-8; 11:8).

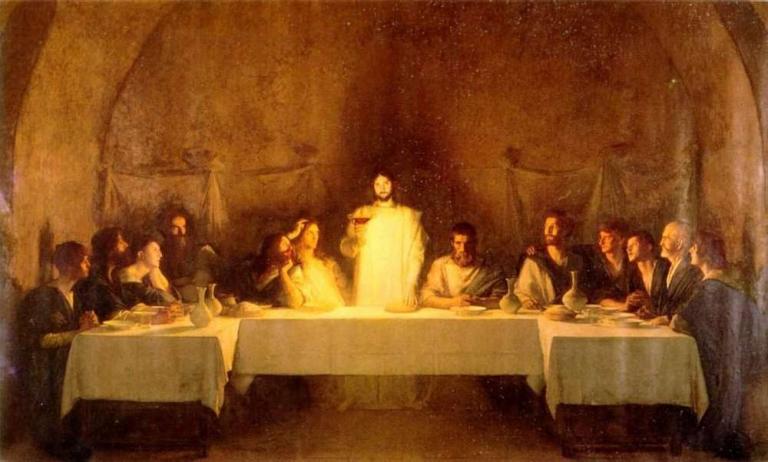

But here is another such passage that is quite striking. It is from Peter’s speech at the Jewish Temple in Acts 3, exhorting the “men of Israel” to reconsider their opposition to Jesus as messiah, whom their leaders had recently persuaded the Romans to kill. Peter immediately concedes the Jewish leaders did this “in ignorance.” Then he urges them to change their minds.

19 Repent therefore and turn for the blotting out of your sins.

20 so that the times of refreshing might come from the face of the Lord and so that he might send the messiah appointed for you—Jesus.

21 whom heaven must receive until the times of restoration of all things which God spoke through the mouth of his holy prophets from ancient time.

This speech is evidence that Peter believed there would be a future for Israel as a distinct entity and land in the future. For the Greek word he uses here for restoration is the same word (apokatastasis) used in the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Old Testament) for God’s future return of Jews from all over the world to Israel.

Jer 16.15 I will bring them back [apokatastēso] to their own land that I gave to their fathers.

Jer 24.6 I will set my eyes on them for good, and I will bring them back [apokatastēso] to this land.

Jer 50 [27 LXX].19 I will restore Israel [apokatastēso] to his pasture.

Hos 11.11 They shall come trembling like birds from Egypt, and like doves from the land of Assyria, and I will return [apokatastēso] them to their homes, declares the LORD.

It can be objected that these prophets might have been referring to the return of Jews to the Land under Ezra and Nehemiah after the exile to Babylon, or to the hundred years of the Hasmonean period.

But the objection cannot be sustained for two reasons. First, Jeremiah and other prophets predicted a return from all over the world, not just Babylon or adjoining lands.

Second, and more telling, Peter used the same word they used for “return to the land,” but applied it to his future. He said the prophets’ predictions about return to the land—no matter whether they were partially fulfilled in previous centuries—were yet to be fulfilled.

Jews never returned to the land to control it, as “restoration” implies, until 1948.

Peter, then, saw a distinct future for the land of Israel in God’s redemptive unfolding of history.

The “restoration” of which he spoke referred not to the whole world but to a Jewish return to the Jewish land.

This is not enough upon which to build a theology of Christian Zionism. Far more needs to be shown and argued.

But it is enough to gainsay the oft-repeated claim that there is no future for Israel as a people or land in the New Testament.

Hence today’s land of Israel might indeed have theological significance.