Rhys S. Bezzant thinks so.

Bezzant is an Anglican priest and scholar whose recent book Jonathan Edwards and the Church (Oxford University Press) is a superb analysis of Edwards’s eccesiology.

Some scholars have charged that Jonathan Edwards (1703-58) had no doctrine of the church, evidenced by his failed pastorate (Patricia Tracy), his alleged sectarianism (Roland Bainton), or pietistic individualism stemming from his revivalism (D.G. Hart). But Edwards specialists from Thomas Schafer to Amy Plantinga Pauw, Douglas Sweeney, and Michael McClymond have made article-length arguments for an Edwardsean ecclesiology.

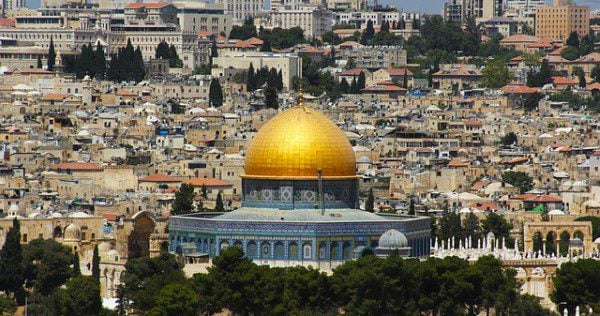

This is the first book-length case for the notion that America’s theologian had a “high view of the church” (4). Bezzant, director of the Edwards Centre Australia at Ridley College in Melbourne, argues that in fact Edwards’s ecclesiology represented a “new stage” (156) in thinking about the society of the saints. “The traditional marks of the church in the Apostles’ Creed as catholic and holy are given new experiential loading” (157), which also went beyond the sixteenth century reformers’ “clerical definition” (156) built on faithful preaching and due administration of the sacraments. Because this was the first time in a millennium that Christians had unbelievers (Native Americans, to whom Edwards was a missionary for almost seven years) for neighbors, Edwards “relativized” Christendom’s model for church. No longer was the church to attend to civil affairs, and now the church was to have a “missionary edge” (168). This also relativized “ossified” Puritan ecclesiology by Edwards’s advocacy of revivals, itinerancy, Concerts of Prayer, missionary initiatives outside the local congregation, and doctrinal clarification (xi).

How did Edwards manage this? Bezzant explains that he tried to “hold together both objective (ministry and means of grace) and subjective (affections and godliness) elements,” thus connecting “the objective nature of God’s consistent and regular offers of grace in the church with the subjective vicissitudes of an individual’s regenerate life” (182). To shape the synthesis, Edwards used the language of “communion” because it suggested “subjective participation in God without allowing for objective absorption into God” (182). Therefore Edwards was not among the radical New Lights who opposed traditional authority for the sake of individual freedom (240). Instead, Edwards argued in his Religious Affections that Christian experience is “accountable” to the church, for it is the church that must judge whether acts of love crown testimonies of spiritual experience. Hence Edwards wanted to unite “ardor” with “order” (124).

But at the same time Edwards’s revival theology provided a source of “innovation” and disruption that was necessary to “destabilize” calcified church orders. Here Bezzant has New England Puritanism of the early eighteenth century in mind. Edwards’s “avowed voluntarism,” when combined with itinerancy and revival, ensured that God would “reserve the right to break into this world apart from regularly constituted means” (210).

Bezzant insists that for Edwards the church is central to Christian experience. In his Miscellanies Edwards wrote that “the church is said to be the completeness of Christ (Eph. 1:23), as if Christ were not complete without the church” (Works of Jonathan Edwards [Yale edn.] 13:272). Furthermore, the New England theologian believed that “the end of the creation was to provide a spouse for his Son” (Works of Jonathan Edwards [Yale edn.] 8:708). Bezzant adds that the progress of the church in its experience of redemption is the main story line of Edwards’s History of the Work of Redemption. Not that progress is “steady” (107), but ever-increasing union is the larger graph of the church’s relation to its Head, and each member’s relation to the Trinity. In fact, Bezzant compares Edwards’s trinitarianism to his ecclesiology, and says the two are related. Just as the Trinity is what Edwards calls a “society” of equals but whose Father “acts as the head” (61), so the church is a fellowship of priests who submit to an ordained ministry. It is hierarchical but not sacerdotal (188).

Bezzant suggests that Edwards evolved in his view of the church. After an early trust in congregationalism, his experience of the revivals moved him toward a Presbyterian polity: “[H]is model could be understood to shift radically the locus of power from the assembled congregation to its agents, who are investing in a common interest beyond the boundaries of the local congregation for which they are demanding increased trust and perversely thereby generating a culture of suspicion” (250-51).

Edwards ran into a buzzsaw of suspicion that caused his eventual ouster from his Northampton pulpit after twenty-three years of ministry there. Bezzant rightly explains that while the formal cause was his policy for admission to communion, this has been often misunderstood as dictatorial presumption that he could read an applicant’s heart. The reality was that Edwards exercised “charity” (180), accepting the testimony of those who believed grace was at work in them.

There are some surprises in Edwards’s ecclesiology. Edwards believed it was the “responsibility” of clergy to conduct “liturgies,” and the “duty” to all believers to attend “external worship” weekly (122-23). Like Calvin, Edwards wished for weekly communion but was not able to persuade his congregation to do so (215). He conceived of infant baptism as a work of the Spirit in the children of the elect, and of the eucharist as Christ giving to believers the real presence of his body and blood, but in a spiritual manner. He was ecumenical enough to praise the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Russian Orthodox Church (252), and taught the dominical offices of bishop and deacon, although he typically interpreted the former to be an elder.

My only complaint is that Bezzant does not reflect on the disconnect between his portrayal of Edwards’s high view of the church and his conclusion that polity for Edwards was the bene esse of the local congregation, but not the esse of the church generally (242). Perhaps there is more tension between Edwards’s evangelical emphasis on conversion and experience, on the one hand, and his insistence on visible union among the saints, on the other, than can be sustained.

That is a quibble, however, about a beautifully-written and elegantly executed study. It is a major achievement for not only Edwards studies but for historical studies of Protestant and evangelical ecclesiology more generally. It will be the standard work in the field for many years to come.

Jonathan Edwards and the Church. By Rhys S. Bezzant. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. xii + 314 pp. $49.95 cloth.