We have all been told that the Kingdom of God was at the center of Jesus’ preaching. But what if that Kingdom was not simply hidden in the hearts of men and women, but was also envisioned by Jesus to be an earthly reality in the future, with territorial Israel at its center? That would change the way we understand the prophecies of a future Kingdom in the Old Testament, and the numerous discussions of the Kingdom in the New Testament.

It would also change the way we think of the relationship between the two Testaments. If the New Testament is as thoroughly Jewish as the New Christian Zionism suggests, and if Israel as a people and Land will continue to have theological significance until the end of time, then we Christians should take the Jewish Bible (the Old Testament)–which tells of this people and Land–more seriously. In other words, it is not only the backdrop to the New, and it not only prepares a people and consciousness for the revelation of the messiah, but according to his own testimony (Luke 24.25-27) it is the key to unlocking the mysteries of the Messiah.

The rabbis said that the book of Leviticus is the most important book of all Tanach (the Old Testament) because it is the deepest revelation of the character of the God of Israel as the Holy One, and the most particular blueprint for how his elect people were to maintain communion with him.[1] Since Tanach was Jesus’ Bible, which he said he embodied (John 1:1, 14; 5:46; 8:58), then the book of Leviticus is the most necessary. It provides the clearest way in to the Holy of Holies where Jesus is revealed. Ironically, most Christians think Leviticus is the most impenetrable of all the books of the Bible and read it the least. That might be a sign and even one of the causes of the profound misunderstanding the Church has had of Judaism, and therefore a warning of how far we need to go to see the God of Israel—who, we need to be reminded, is the true God–with sufficient clarity.

Augustine famously pronounced, “In the Old Testament the New Testament is concealed; in the New Testament the Old Testament is revealed.”[2] The New Christian Zionism sheds a bit more light on this truth. Not only is the Old Testament revealed in the New Testament, but the meaning of that revelation is further clarified: Israel is not just a memory in the New, nor is she simply an unwitting witness to the messiah, as Augustine argued.[3] Rather than merely a voice from the past, she is a living presence in the Church and will be the center of the world to come.

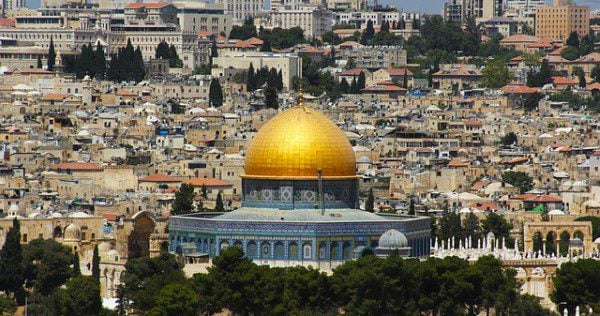

Once translators and readers of the Bible are convinced that Israel is not only past but also present and future, they might see things in the biblical text that were always there but they somehow missed. For example, they might be newly struck by the intimate connection between Jewish history and its Land. The Old Testament text reveals how Jewish laws and customs are based on the Land and its climate, and how its festivals are linked to events on the Land. Passover, for example, is the annual celebration of the original divine gift of the Land, and Hanukkah is the annual festival commemorating the rededication of the temple on the Land.[4] But it is not only the Bible’s historical festivals that mark events on the Land. Its agricultural festivals follow the seasons of the Land: the seven-day springtime festival of Unleavened Bread, around the barley harvest; the early summer festival of harvest, when the wheat ripens (Weeks or Shavuot); and the autumn festival of ingathering, when olives, grapes, and other fruits were harvested (Tabernacles). Even when Jews were living in exile, they pined for the Land: “By the rivers of Babylon—there we sat down and there we wept when we remembered Zion” (Ps 137.1). This is why Jews have said for millennia that they can live as Jews with the greatest integrity only when they are on the Land.

Once they catch this vision, readers might also see for the first time that according to the biblical text, people and Land suffer and prosper together: Obedience brings “prosperity . . . in the fruit of your ground in the Land that the LORD swore to your ancestors to give you,” but disobedience makes “the sky over your head . . . bronze, and the earth under you iron” (Deut 28.11, 23).

They might then realize that their previous assumptions about Israel and the Land—that its importance was temporary, just like that of the sacrificial system or what Christians have called the “ceremonial law”—were wrong. On closer examination of the biblical text, which new understandings of God always brings, they would see that while the Mosaic law–with its “ceremonial” commands about worship–was a sign of the covenant, the Land was part of the covenant itself. This is what Hebrews 8:13 means when it says the first covenant has been made “obsolete.” It refers to the sacrificial system revealed through Moses, which Rome’s destruction of the Temple in 70 AD brought to an end.[5] But the Land was the principal gift of God in the master covenant with Abraham in Genesis, and its promise was never revoked.[6]

Scripture never puts the Land on the same level as Mosaic law. If the latter is binding on Jews but not Gentiles in the same way, and the Church is overwhelmingly Gentile, in one sense Gentiles can say that it has become obsolete (but not irrelevant) for them. But they can never say that about the people of Israel or the Land of Israel. The Gentiles of faith have been grafted into the olive tree of the people of Israel. And the Land of Israel is God’s “holy abode” (Ex 15.13). As the earlier chapters have shown, the New Testament authors believed the Land continued to be God’s holy abode.

The New Christian Zionism also suggests that we should put away our old assumptions about the Old Testament “dispensation of law” and its “legalistic” treatment of the Land. As many scholars have shown, it is true that Israel’s enjoyment of the Land was conditional: they were exiled when they disobeyed the terms of the Mosaic covenant. But just as the original gift of the Land was unconditional and forever, so too the return to the Land was a gift of grace. Repentance did not precede it. The scriptures suggest instead that repentance and full spiritual renewal will take place after return and restoration. In Ezekiel’s vision of the resurrection of the dry bones, first God says he will take the people of Israel and “bring them to their own land,” and then at some point which seems to come later, he “will make them one nation in the land” and at what might be a still later point he “will cleanse them” (Ezek 37.21, 22, 23). So the relationship between Israel and the Land, if seen through eyes that are not veiled by supersessionism, is one of unconditional grace as well as conditional law. It takes a new orientation to Israel and Land to see these things.

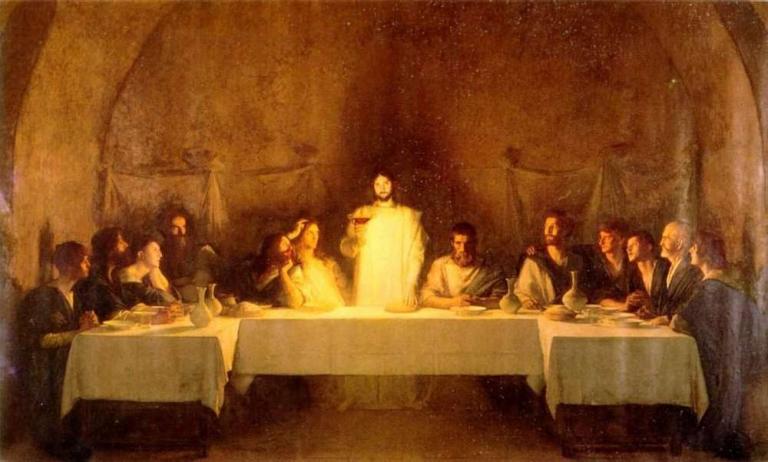

[1] For a contemporary rabbinic estimation of Leviticus as “the key text of Judaism,” see Jonathan Sacks, “Leviticus: The Democratisation of Holiness,” 1-3, http://www.rabbisacks.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CCVayikraPreview.pdf (accessed July 7, 2015). [2] Augustine, Quaest. in Hept. 2, 73. [3] Paula Fredriksen, Augustine and the Jews: A Christian Defense of Jews and Judaism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010). [4]Of course, the rededication of the temple is recorded in 2 Maccabees, which is typically not included in Protestant Bibles. [5] Hebrews moves directly from its statement of the first covenant being obsolete to a discussion of the tabernacle in the wilderness where “sacrifices are offered that cannot perfect the conscience of the worshiper” (Heb. 9:1-2,9). It is clear from this that by “covenant” the text means the Mosaic covenant, not the master covenant cut with Abraham. [6] Jesus spoke of “the blood of the covenant” (Matt 26.28; Mk 14.24), suggesting there was only one fundamental (Abrahamic) covenant, and that the Mosaic law was an aspect of but not the same as that fundamental covenant.