I mourn the death of Michael Wyschogrod on December 17. He was one of the great Jewish philosophers and theologians of the 20th century. He was also one of the only ones to affirm the concept of incarnation, while denying that Jesus was the actual incarnation of God.

I count it as one of the joys of my life that I got to know Dr. Wyschogrod a bit, and to work with him a little. He was one of the participants in a Jewish-Christian dialogue group I had the good fortune to be part of for a number of years.

Wyschogrod stood with his father in the streets of Berlin on Kristallnacht watching Nazi Brownshirts unroll a Torah scroll on the ground so that passersby could trample it in derision. He went on to write what has been hailed as perhaps the greatest Jewish theology of the last century, The Body of Faith: God in the People Israel.

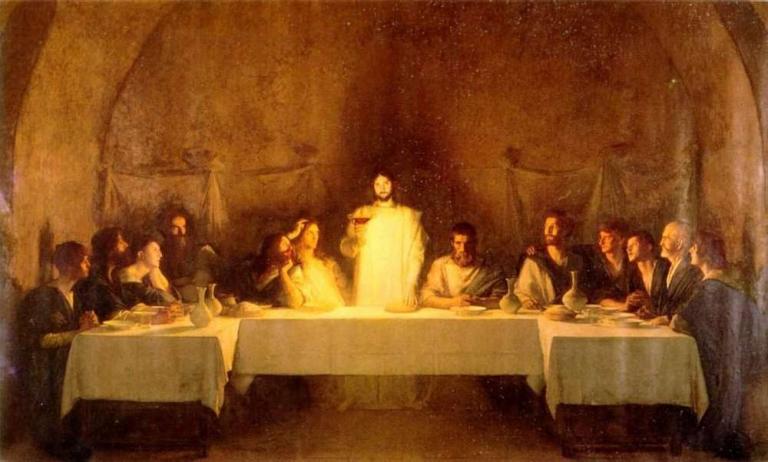

Inspired by both Kierkegaard and Barth, Wyschogrod wrote that the concept of incarnation is Jewish, for it expresses the deep truth that God is somehow incarnated in his people Israel. Although he denied the Incarnation in Jesus, he nevertheless called the Christian doctrine a more concentrated version of the true Jewish doctrine.

Wyschogrod was among few Jewish thinkers willing to meet with and engage in dialogue with messianic Jewish thinkers.

He also criticized Jewish philosophers who ignored the God of the Bible. He warned, as Barth did, against letting the God of the Bible be defined by a philosophical or even theological system.

Wyschogrod had little time for dialogue that is content with minimal niceties and fails to engage deepest differences. He said Jews are obligated to warn their Christian friends of their possible idolatry in worshiping a man. I appreciated that warning, and responded with my own articulation of Christian distinctions. I think I can say honestly that he seemed to enjoy my arguments, and I relished his. I will never forget his arguing vociferously with his Jewish colleagues over more than a few points of Jewish belief and practice, and their warm embraces following what seemed to be intense differences. The depth of argument in an atmosphere of genuine love was what struck me–as a model for theological dialogue.

I thank JoAnn Magnuson for sending this tribute.