One reason why many Christians and secularists dismiss Christian (and Jewish!) Zionism is that they think it is one example of many nationalisms that arose in the nineteenth century, when Romanticism and European democratic movements were inspiring many peoples of common culture to form nation-states. The implication is that Zionism is therefore recent and political, and cannot be essentially related to ancient times and religion, as religious Zionists claim it is.

The first problem with this charge is that there is plenty of evidence, as I will show in The New Christian Zionism (IVP Academic, August this year), that Christian Zionism goes back two thousand years to the New Testament, and was sustained with varying intensity ever since. There I show that Jewish Zionism is even older, stretching back at least three thousand years.

But what of Zionism’s relation to nineteenth-century nationalist movements? It is true that the rise of political Zionism in the nineteenth century followed, and to a degree benefited from, the romantic nationalism that was inspired by Rousseau (1712-1778) and Herder (1744-1803), who suggested that a people are formed by geography, language, customs, and (for some) race. These new cultural winds helped form Germany, Italy, and Romania by unifying what had been regional states, and helped wars of independence to create Greece, Bulgaria and Poland.[1]

Yet four of these nationalisms—Germany, Romania, Bulgaria, and Poland—were unable to go back more than a few centuries to a previous unity of culture or language or religion. Germany had no common language before the sixteenth century. Only Greece and Italy could point to ancient civilizations on the same land, yet the religion (and therefore culture) of each in the nineteenth century was dramatically different from what obtained in their ancient predecessors. Israel alone can point to an ancient civilization on the same land with the same religion and language.[2] Nineteenth-century nationalism might have assisted the rise of Zionism, but the heightened anti-semitism in Europe (which ironically was strengthened by the new race consciousness in that same nineteenth-century romantic nationalism) and vicious pogroms in Russia did far more than romantic nationalism to allow the ancient Zionist idea to blossom into Theodore Herzl’s political Zionism in the late nineteenth century.[3]

Besides, a growing number of scholars are saying that the notion of European nationalism arising from Rousseau and Herder is more myth than fact, or at best grossly incomplete. These scholars argue that European nationalism had its source in the Hebrew Bible, and in the adoption by European peoples of national identities consciously modeled upon the national identity of biblical Israel—a modern phenomenon greatly accelerated by the vernacular Bible and Protestantism. By the late sixteenth century, for example, England and Holland were already European nations with self-understandings based on the Bible’s division of the world into nations as God-given, and the independence of nations as a biblical ideal.[4]

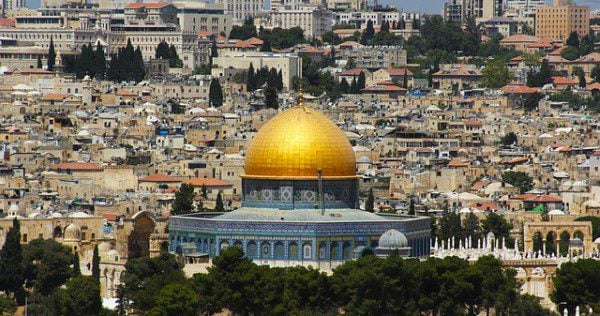

No matter the character of modern nationalism, Jews have lived in the land of Israel for three thousand years, all the while thinking of themselves as Jews in the homeland for Jewish culture. This means that Jews thought of Israel as the natural home for Jews for millennia before the nineteen century. Besides the continual residence of Jews in the land from Joshua’s conquests in the thirteenth century BC to the Bar Kochba revolt in 135 AD—the continual residence of which most historians acknowledge—four times in the last two thousand years the land of Israel served as the refuge for, and rebuilding of, Jewish culture.[5]

The first time that Jews regrouped in the land was after the two wars with Rome in 66-70 and 132-35. The rabbis were driven out of Jerusalem up to Galilee, where they compiled the Mishna, a creative reinterpretation of Torah after the destruction of the Temple forced Jews to see Torah study as the new sacrifice. The northernmost land of Israel, Galilee, served as a center of Jewish culture for the next five hundred years.[6]

Later, after Jews fled Baghdad (where they had flourished for a time) in the eighth century when Turkish invasions destroyed the stability of the Abbasid caliphate, Tiberias in Galilee once again became a center for Jewish culture. It was here that the Masoretic text of the TaNaKh was produced. From the eight through the tenth centuries Galilee once again was a center of Jewish religious thought and life.[7]

A third time was after a century of Jewish martyrdom at the hand of Christian Europeans, a century that included the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) compelling Jews to wear a badge and the expulsion of Jews from Spain (1492) and Portugal (1496). When the Ottoman sultan Selim the Terrible in 1517 ousted the Mamelukes from Jerusalem, he opened the doors of Palestine to Jewish immigration once more. Small numbers of Jews had been living on the land all along, but now the Jewish population grew in numbers and prosperity. Safed in Galilee became the new center of rabbinic culture, and produced two of its greatest sages in the sixteenth century, Joseph Caro and Isaac Luria. There they developed Kabbalah, the mystical Judaism that brought life and hope to Jews in later centuries. Safed became a pilgrimage site for Polish Hasidim (lit., “the pious ones”; Jewish mystics) from the sixteenth through the nineteenth centuries.[8] In addition, many students of Rabbi Elijah of Vilna emigrated from Lithuania to Israel at the end of the eighteenth century to found what became known as the “old Yishuv” (“the original community”) outside the ancient city walls of Jerusalem.

Finally, when Tsarist pogroms drove Jews from Russia, and modern antisemitism in Europe started boiling over in the nineteenth century, Jews once again came to Israel for a refuge and cultural homeland. But they started coming long before the rise of what we now call Zionism, led by Theodore Herzl (1860-1904). For example, three hundred rabbis and their families moved to Ottoman Palestine in the eighteenth century pursuing their vision of redemption in the Land.[9] Others followed. The first wave of Jewish refugees from Europe came in 1882 to join the Sephardic Jews who had lived in Palestine for generations. Herzl did not organize the first Zionist Congress until 1897.[10]

So Zionism can rightly be called a nationalism because it is a sense of unity based on common customs, language, and religious culture. But limiting its origins to the late nineteenth century contradicts its actual history.[11] Jews have been on the land for more than three thousand years, and have always regarded it as their cultural and religious home. Indeed, it has been a place of pilgrimage for Jews in the diaspora for more than two thousand years.

[1] Eric J. Hobsbawm, .Nations and Nationalism Since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

[2] From the second century AD until the revival of Hebrew as a spoken language circa 1880, Hebrew was employed as a literary and official language and the language of prayer. Chaim Rabin, A Short History of the Hebrew Language (Jerusalem: Jewish Agency and Alpha Press, 1973).

3 Leon Poliakov, The History of Anti-Semitism, Vol. 3: From Voltaire to Wagner (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003).

[4] See, for example, Adrian Hastings, The Construction of Nationhood: Ethnicity, Religion and Nationalism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

[5] James Parkes, End of an Exile: Israel, the Jews and the Gentile World, eds. Eugene B. Korn and Roberta Kalechofsky (Marblehead, MA: Micah Publications, 2004), 26-34.

[6] “Despite the negative factors at work [persecution of Jews during the Byzantine period], it can be stated that most of the Galilee retained its Jewish character through the sixth century.” Alon, The Jews in the Land, 755.

[7] See “The Masoretes and the Punctuation of Biblical Hebrew,” British and Foreign Bible Society, http://lc.bfbs.org.uk/e107_files/downloads/masoretes.pdf; Elvira Martín Contreras, “Masora and Masoretic Interpretation,” in Steven L. Mckenzie, ed., The Oxford Encyclopedia of Biblical Interpretation, 2 vols., forthcoming; Paul Johnson, A History of the Jews (New York: Harper and Row, 1987), 151-52.

[8] Johnson, A History of the Jews, 260-61.

[9] Shalom Goldman, Zeal for Zion: Christians, Jews, and the Idea of the Promised Land (chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 10.

[10] Parkes, End of an Exile, 24; Johnson, A History of the Jews, 357-65;

[11] Johnson, A History of the Jews, 374-75.