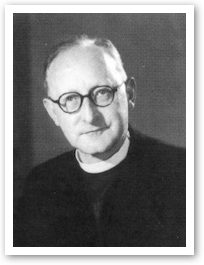

One of the greatest Anglican books of the 20th century is about to be republished on this side of the pond. This is a cause for rejoicing. Not only because E.L. Mascall was a great (and orthodox) Anglican theologian, but also because this book will help solve numerous theological problems for Christians in this troubled century. Besides, as a stutterer who has written about famous stutterers, I am sympathetic to theologians who have a speech defect, as Mascall did.

One of the greatest Anglican books of the 20th century is about to be republished on this side of the pond. This is a cause for rejoicing. Not only because E.L. Mascall was a great (and orthodox) Anglican theologian, but also because this book will help solve numerous theological problems for Christians in this troubled century. Besides, as a stutterer who has written about famous stutterers, I am sympathetic to theologians who have a speech defect, as Mascall did.

Here is an excerpt from my foreword to this new edition of Christ, the Christian and the Church (Hendrickson, Fall 2017).

Eric Lionel Mascall (1905-93) was one of the best–perhaps the sharpest and most lucid–of orthodox Anglican theologians in the twentieth century. An Anglican priest who finished his career as Professor of Historical Theology at King’s College in the University of London, Mascall excelled in mathematics at the university, and boasted of never having been formally trained in graduate-level theology. These two facts might help explain why his theology was hailed for being so wide-ranging, incisive, and elegant.

Mascall wrote books in both philosophical and dogmatic theology. He was chosen to deliver two of Britain’s most prestigious lecture series, the Gifford and Bampton Lectures. The first was published as The Openness of Being (1971), and the second as Christian Theology and Natural Science (1956). The latter was celebrated by some as the best treatment to that day of the relationship between Christian faith and modern science.

The scope of Mascall’s writings was broad. He did serious work on the subjects of creation, epistemology, religious language, the Incarnation, the Trinity, the Church, ministry, and sacraments. He determined to converse with Protestants, Catholics, and Eastern Orthodox, and read their best theologians. His thinking displayed an oft-noted balance—between reason and revelation, the natural and the supernatural (nature and grace), philosophy and theology. Unlike some of his century’s theologians, he accepted the traditional theism of the Thomistic tradition, and rejected process and Hegelian thought. He believed in a properly Christian natural theology, but insisted that special revelation surpasses and controls what nature and reason show of God. He accepted the analogy of being, but did not believe that classical proofs could provide certainty. True faith, for Mascall, is a work of the Spirit that provides intuitive confirmation of what revelation declares. For this modest and gentle but humorous Anglican, the Christian life is a matter of daily liturgical prayer, participation in the sacraments especially Eucharist, and gradual transformation by incorporation into Christ through his Church.

Christ, Christian and the Church (1946) is the closest thing we have to a Mascallian systematic theology. It is dedicated to the proposition that the center of Christian faith is the Incarnation. By baptism, he asserts, men and women are recreated through incorporation into the human nature of Jesus. Sanctification is the progressive realization in the moral realm of the change made in the ontological realm by baptism. Incorporation into Christ is incorporation into the Church, which is a living organism. The Church in its essence is simply the human nature of Christ. All the thought, prayer, and activity of Christians—insofar as they are brought into the sphere of redemption—are the acts of Christ himself in and through his Body. The thread that unites all these ideas for Mascall is the doctrine of the permanence of the manhood of the glorified and ascended Christ. This, he maintains, is the central principle of Christian theology.

Mascall’s balanced focus on the Incarnation eliminates the false binaries that bedevil so much of the Church today. In the treatise that follows, he shows that justification involves both imputation and impartation, that eschatology is both realized and futurist, that grace is offered universally and the Church is the only ark of salvation, that the Eucharist is both participation in the worship of heaven and the re-presentation of the once-for-all sacrifice of Calvary, that Christian faith must rest on both personal devotion and liturgical worship, that faith is not opposed to (orthodox) mysticism, and that revelation containing both propositions and mysterious images is compatible with rational (but not rationalistic) theology.

The chapters that follow explore the Incarnation, Christology, atonement, incorporation, ecclesiology, anthropology, Eucharist, prayer, and theology. Let me suggest briefly eight ways in which these chapters might help rectify some theological problems facing the Church today.

First, Mascall’s emphasis on Incarnation can help address a gospel minimalism that would reduce the faith to a legal transaction in the sky, removed from the sinner’s inmost self. Mascall insists that because the Son took human nature up into himself, he “supernaturalizes” (80) the person to whom he is joined by faith. Therefore justification is not merely forensic. God does not impute without also imparting life in and with Christ. Becoming a Christian means being incorporated into the glorified manhood of the ascended Christ.

Second, worship is not watching performers in a rock band or listening to an intellectual explication of biblical texts. Instead it is being caught up into the act whereby Christ eternally adores the heavenly Father, as we sit with him in heavenly places. Worship is the raison d’etre of the Church, God the Spirit offering God the Son to God the Father in an eternal celebration we are enabled to join. Preaching is of course part of every good worship service, but its final purpose is adoration.

Third, the Church is not a voluntary association of like-minded people, but a Body of people ontologically joined to the glorified manhood of Jesus. The life of the Church is the life of the Trinity imparted to men and women. It is not merely a society of people associated with God, but the divine Society itself, the life of the Godhead reaching out to humanity and taking humanity up into itself. It is not an organization but an organism. . . .