This is the third in a series analyzing two books, one by Dom Gregory Dix and the other by Paul Bradshaw. Today we continue with Dix, The Shape of the Liturgy.

- The classical shape of the liturgy—the Eucharist

- It was regarded as the solemn putting into act before God of the whole Xn living of the church’s members

- In the East in the 3rd c. the deacon would cry, while the kiss was being exchanged, “Is there any man who keeps anything against his fellow?”

- By the 4th c. it had become this warning: “Let none keep rancor against any! Let none (give the kiss) in hypocrisy!” 107

- The Church inherited the kiss of peace from Judaism

- In Jesus’ time the kiss was a courteous preliminary to any ceremonial meal.

- Although the offertory (at first merely “taking” the bread and wine before they could be blessed) was not always sharply distinguished from what followed, it was a ritual act with a significance of its own.

- In the Apostolic Tradition [according to Bradshaw, from mid-2nd to 4th c.]: “To (the bishop) then let the deacons bring up the oblation (prosphora) and he with all the presbyters laying his hand on the oblation shall say “eucharistising” thus . . .”

- Back in the mid-2nd c. Justin Martyr uses the technical term prospheretai and refers to them as “sacrifices which are offered to God by us gentiles, that is the bread of the eucharist and the cup likewise of the eucharist” (Dialogue 41).

- Back in the last years of the first c. Clement of Rome wrote that the “bishop’s office” was to “offer the gifts” (prospherein ta dora) (1 Clement 44). 111

- Soon after 200 Tertullian is explicit that the eucharist is a sacrificium, and that the material of the sacrifice is the oblationes brought by the people.

- In the mid-3rd c. Cyprian specifies how the eucharist is thought to be a sacrifice: “The passion [of Jesus at Calvary] is the Lord’s sacrifice which we offer” (Ep. 63, 17). 115

- Irenaeus (d. 202) wrote that each communicant gave himself under the forms of bread and wine to God, as God gives Himself to them under the same forms. Dix: “In Christ, as His Body, the church is ‘accepted’ by God ‘in the Beloved.’ Its sacrifice of itself is taken up into His sacrifice of Himself. . . . The offering of themselves by the members of Christ could not be acceptable to God unless taken up into the offering of Himself by Christ in consecration and communion.” 117-18

- The Last Supper was not a eucharist properly speaking because Calvary was not yet an accomplished fact.

- No ancient liturgical institution narrative was simply a quotation from scripture. They all adapt and expand our Lord’s words as reported in the NT, sometimes very boldly. 133

- Every 2nd writer is strong on the identification of the consecrated elements with the Body and Blood. In Justin’s First Apology, e.g., he writes, the consecrated bread and wine “is (esti) the Flesh and Blood of that Jesus who was made flesh” (Ap. I, 65).

- A subtle transformation of understanding took place over the 3rd and 4th cs: the original eschatological understanding of the eucharist as an irruption into time of the heavenly Christ, and of the eucharist as actualizing an eternal redemption in the earthly church as Body of Christ in the world, was replaced by a new insistence on the purely historical achievement of redemption w/in this world and time by Christ, at a particular moment and by particular actions in the past. 139

- It was regarded as the solemn putting into act before God of the whole Xn living of the church’s members

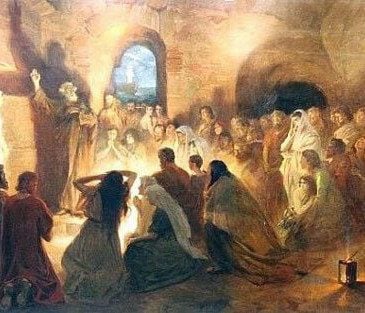

- The pre-Nicene background of the liturgy

- Early Christians, in an Empire where it was dangerous to worship as a Xn, would not run risks to attend worship merely to rememeber with thankfulness in a specially moving way the death of Jesus which had redeemed them. 151

- There were no devotional practices in the primitive Eucharistic rite that were calculated to arouse a subjective piety—such as confession or devotions in preparation for communion, not even a corporate thanksgiving—nothing except the bare requisites for the sacramental act. 151

- “It was a burning faith in the vital importance of that Eucharistic action as such, its importance to God and to the church and to a man’s own soul, for this world and for the next, which made the Xns cling to the rite of the eucharist against all odds.” 151

- The Middle Ages distorted that corporate act into a focus for subjective individual piety. 155