Paul F. Bradshaw, The Search for the Origins of Christian Worship

Ancient church orders

82-83 Bradshaw argues that Hippolytus’ Apostolic Tradition, typically dated c. 215 and placed at Rome, was a composite work from disparate traditions, containing materials from the 2nd thru the 4th cs., and probably did not represent the practice of any single Xn community. His evidence? The work of a Marcel Metzger who points to “its lack of unity or logical progression, its frequent incoherences, doublets, and contradictions.”

[I am not sure we should accept Metzger or Bradshaw as our final authorities on this. Their method is that of source criticism, which is widely regarded as not as reliable as scholars used to think. It is quite clear that whether Metzger or Bradshaw are right or not, the Tradition represents the thinking of influential early Christian liturgists. As Bradshaw says on 96, the AT was translated and copied so many times because it was exactly what later eyes were looking for—the beginning of liturgical rubrics and canon law. That alone is significant.] [I remember studying form and source criticism at the University of Chicago Divinity School back in the early 1970s. I was struck by how the critics often disagreed with one another, and yet each thought he (almost all were men) got it right. I remember concluding that their sometimes-radical disagreements showed the speculative and iffy character of their methods, as scholars decades later came to show.]92-93 Bradshaw claims the Didache also evolved by stages and that scholars are divided over the antiquity of its different parts. [again, this is another result of speculative source criticism. More recent scholars such as Michael Svigel argue for a Didache date within the lifetime of the apostles.]

95 Bradshaw claims without argument that the Pastoral Epistles are pseudepigraphical. [NT Wright is not so sure.]

In conclusion, Bradshaw is a splitter. He breaks up the lumps that previous scholars had gathered, and asks critical questions about the integrity of those lumps. That’s not all bad. We don’t want to make false assumptions about dates and authors. But at the same time we don’t want to make equally false presumptions such as the following—that there was no consensus among early church liturgists, or that we cannot discern any agreements about sacraments or liturgy.

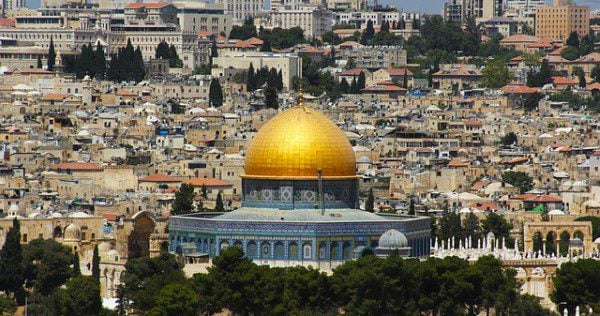

And if we find that there were significant changes in liturgy over the first four centuries, such as a movement from diversity to uniformity, this should not call into question the integrity of later liturgical agreements that trace back more to the 4th than to the 2nd century. For if Jesus promised that the Spirit would guide the church on things that Jesus did not spell out explicitly (John 16.12-15)—and even low-church evangelicals agree that the Spirit did just that on the doctrine of the Trinity in the first four centuries—we can believe that the Spirit was guiding the Church in those same centuries as it joined the Son in offering worship to the Father “decently and in order” (1 Cor 14.40) and with “the beauty of holiness” (Ps 96.9).