As James K.A. Smith has shown recently, every church–and for that matter sports teams and countries–have their own liturgies, which means they have their own public rites and ceremonies. But some churches are known to be “liturgical.” They have ancient forms of prayers and sacraments that they use every week. Why do they use these rites and forms?

As James K.A. Smith has shown recently, every church–and for that matter sports teams and countries–have their own liturgies, which means they have their own public rites and ceremonies. But some churches are known to be “liturgical.” They have ancient forms of prayers and sacraments that they use every week. Why do they use these rites and forms?

Liturgy comes from a Greek word which means “the work of the people.” In this ancient custom of worship worshipers become as a group of Christians what they cannot be as individuals—the people of God. They worship publicly according to established patterns or forms that have passed down to us from Israel’s worship and from the early Church.

Liturgy is an answer to the disciples’ request of Jesus, “Lord teach us to pray.” In other words, How do we pray?

It is behind Paul’s statement in Romans 8, “We do not know how to pray as we ought” (v. 26).

It helps explain why God struck down Nadab and Abihu (Lev. 10) when they offered unholy fire. They thought they could figure out on their own how to worship–rather than recognizing that God had already given precise instruction on how Israel was to worship.

Liturgy is worship that joins in Christ’s worship of His Father. So it is participating with Christ in his offering Himself and His Body to the Father. It is joining with the saints and angels in their celestial worship.

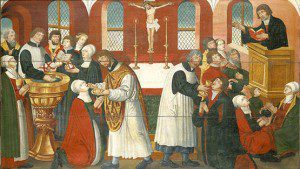

Unlike many “low” churches today, in liturgical worship the people in the pews participate in worship through song and response and joining with the ministers in confession and prayer and worship. In many low churches all the action is up front, and the people watching are doing just that—being spectators not participants. But in a liturgical church the priest/minister leads us as we worship together, singing and praying in adoration together. This is why liturgy is called the “work of the people.”

The early church did not make up this liturgy from scratch. They derived most of it from the Jewish liturgy, and brought out its messianic meanings. So, for example, there was an entrance rite in the Temple liturgies, based on Ps 122.1, “I was glad when they said to me, ‘Let us go up to the house of the Lord.’” The Levite singers would go in a procession before the priests, who would bring up the ark of the covenant (before the temple was built), which contained the two tablets of God’s words and the manna that God fed them with in the wilderness. The two basic parts of the Christian liturgy—the liturgy of the Word and the liturgy of the Table—are based ultimately on these two features of Jewish history and worship.

Liturgical churches are sacramental churches. They celebrate the sacrament of communion every week, not just on certain Sundays of the year. They believe communion is not merely a remembrance of what happened two thousand years ago, but the celebration of and participation in the Real Presence of the Body and Blood of Christ. They consider baptism to be not merely what we do to proclaim our faith but also something that happens to us in a special way by the Holy Spirit, planting a real seed that must then be watered and nourished by learning and fellowship and faith.

Liturgical churches follow the church year, which is a way coming from the ancient church that takes them through the great seasons of Christian life every year—seasons that re-present to us the whole history of Israel and Jesus Christ. The whole year is divided into two parts that follow the same three-fold pattern: remembering and repenting our sin (Advent and Lent), celebrating God’s acts to redeem us from sin (Christmas season and Passion week and Easter season), and then our response of gratitude and obedience (Epiphany and Pentecost).