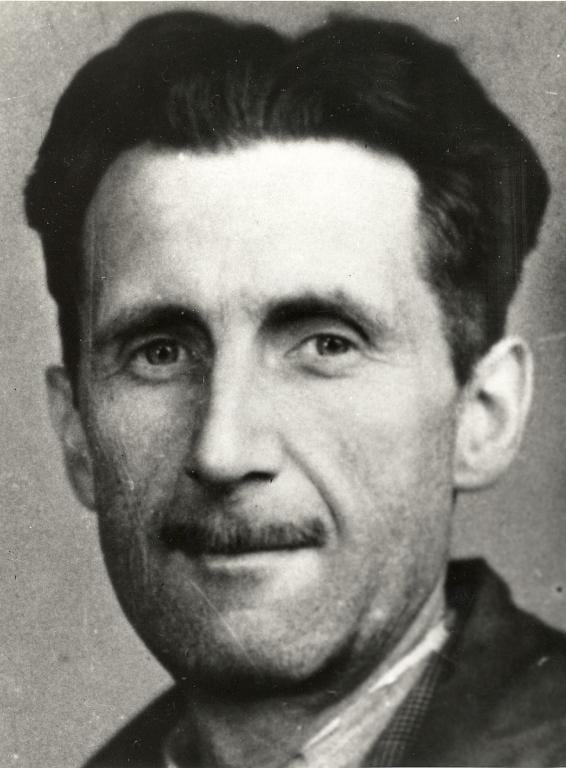

George Orwell is now revered as one of the most gifted and courageous writers of the twentieth century. His Animal Farm and 1984 are regarded as brilliant exposés of communism that were penned when its totalitarian tyranny was fairly unknown. But as Christopher Hitchens’ Why Orwell Matters shows, Orwell’s gifts were largely overlooked by his contemporaries. Animal Farm almost never got published during his lifetime because it was misunderstood: in 1944 T.S. Eliot, editor at Faber and Faber, thought it was “Trotskyite” and rejected it for fear that its criticism of the Soviet Union would not be accepted as long as Stalin was a British ally against Germany. When Orwell turned to an American publisher, he was told that Americans would not read literature about talking animals. This was an America already enjoying Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. As Hitchens observed, Orwell struggled throughout his career “first for the principles he espoused and second for the right to witness to them.” (Basic Books, 2002, p. 5)

George Orwell is now revered as one of the most gifted and courageous writers of the twentieth century. His Animal Farm and 1984 are regarded as brilliant exposés of communism that were penned when its totalitarian tyranny was fairly unknown. But as Christopher Hitchens’ Why Orwell Matters shows, Orwell’s gifts were largely overlooked by his contemporaries. Animal Farm almost never got published during his lifetime because it was misunderstood: in 1944 T.S. Eliot, editor at Faber and Faber, thought it was “Trotskyite” and rejected it for fear that its criticism of the Soviet Union would not be accepted as long as Stalin was a British ally against Germany. When Orwell turned to an American publisher, he was told that Americans would not read literature about talking animals. This was an America already enjoying Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. As Hitchens observed, Orwell struggled throughout his career “first for the principles he espoused and second for the right to witness to them.” (Basic Books, 2002, p. 5)

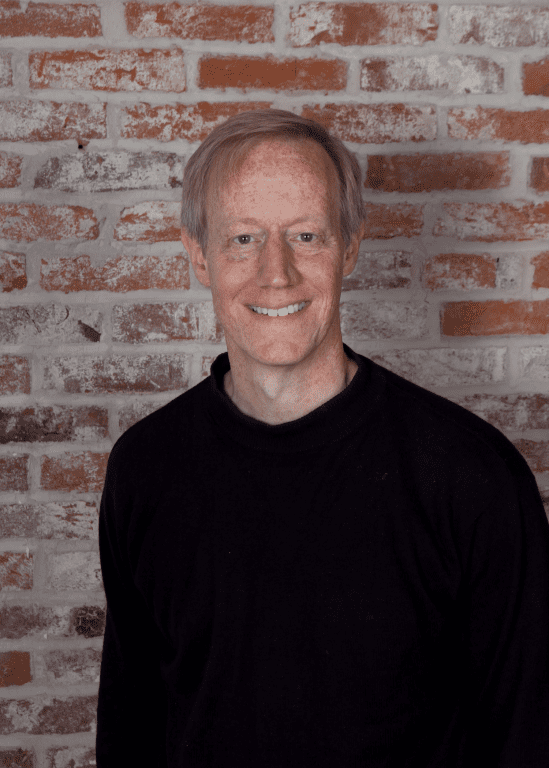

Today we have another Orwell, not in social or political essays but historical theology. In June 2018 Michael McClymond published The Devil’s Redemption, the first-ever academic critical history of the doctrine of universalism. With engaging prose accessible to non-theologians, McClymond surveys this vast history in 1400 pages over two volumes, patiently detailing the arguments and contexts of more than one hundred fifty major thinkers. He traces the arguments historically, from the second century to the twenty-first, but also exegetically, philosophically, and theologically. In the process he demonstrates that the doctrine of universal salvation—that there is no hell or that hell is only temporary—cannot be sustained without doing violence to every other major Christian dogma.

Today we have another Orwell, not in social or political essays but historical theology. In June 2018 Michael McClymond published The Devil’s Redemption, the first-ever academic critical history of the doctrine of universalism. With engaging prose accessible to non-theologians, McClymond surveys this vast history in 1400 pages over two volumes, patiently detailing the arguments and contexts of more than one hundred fifty major thinkers. He traces the arguments historically, from the second century to the twenty-first, but also exegetically, philosophically, and theologically. In the process he demonstrates that the doctrine of universal salvation—that there is no hell or that hell is only temporary—cannot be sustained without doing violence to every other major Christian dogma.

Plaudits have come from highly-respected theologians and historians. Yale’s Lamin Sanneh wrote that The Devil’s Redemption “will establish itself as a standard work of scholarship in the field.” Evangelical theologian Kevin Vanhoozer opines that “McClymond has produced what I suspect will be the definitive treatment of Christian universalism for years to come.” Renowned Catholic theologian Matthew Levering says, “This is a page-turner that both sides will have to read.” Douglas Sweeney at Beeson Divinity School calls it “a tour de force of historical theology.” Amos Yong at Fuller hails it as “Erudite! Encyclopedic! Exhaustive!” The celebrated New Testament scholar Craig Keener describes it as “a timely and fascinating book on a crucial topic that probably only an omnicompetent historical theologian like Michael McClymond could write.”

So why has almost no major academic journal reviewed it? Only The International Journal of Systematic Theology and Pneuma, a journal of Pentecostal studies, have given it full-length reviews. An essay on universalism treated it in Modern Theology, but the essay was not a standard book review of the sort that the journal typically runs. Douglas Farrow reviewed it in First Things, but this is not a standard academic journal. Where are the major historical and theological journals such as Theology Today, the Scottish Journal of Theology, Church History, Journal of Religion, Harvard Theological Review, Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Journal of Ecumenical Studies, Princeton Theological Review, Theological Studies?

Of course it will only be two years in June since the book appeared, and the gears of academic reviewing turn slowly. Yet by two years time most other attention-getting books in theology have been reviewed by at least half of the major journals. But not McClymond’s monumental tome. Why not?

I think there are two reasons. First, the Orwell syndrome. Like Orwell, McClymond is pushing back against what has become orthodoxy in so much of the theological world in the last century. Almost all of mainline Protestant theology has adopted universalism, following Barth who famously wrote, “I am not a universalist. But I am not not a universalist.” (Yes, a double negative). After all, Barth has been the single most influential theologian of the last century, not only among Protestants (and increasingly among evangelicals) but also among Catholics. The Catholic theologian who has become increasingly influential across the Tiber since 1980 is Hans Urs von Balthasar, and he himself was such a fan of Barth’s universalist structure (which points strongly toward universalism despite Barth’s weak denials: see above) that he famously taught a “hopeful” universalism, which insists that Christians have an obligation to hope that God will save all. This despite the fact that Jesus taught that all will not be saved (Matt 10.28; 13.42; 24.51; 25.30, 41-46; Mark 9.48; Luke 16.23). Therefore hopeful universalism means hoping that Jesus was wrong in what he clearly taught. Do we have an obligation to hope that Jesus was wrong?

Theologians are like everyone else: they don’t like to be told that they are wrong. Even when there is massive evidence that they are, as McClymond has shown.

Which brings me to the second reason. McClymond has raised the hackles of David Bentley Hart, a theologian who had won wide and deep respect for his work in past decades. Hart, as you might guess, is a universalist. In fact, in recent years he has launched mean-spirited attacks on all traditionally-orthodox (that is, those who accept what traditional orthodoxy has always taught, that there are two final destinations for human beings, not just one) theologians and Christians. In a New York Times op-ed entitled “Why Do People Believe in Hell?” he attributed this belief to the “deep emotional need . . . of being admired when so many are despised, of being envied when so many have been scorned.” This is Hart’s psychological dismissal of the traditional faith of St. Francis of Assisi, Mother Teresa, and billions of other Christians throughout history.

Which brings me to the second reason. McClymond has raised the hackles of David Bentley Hart, a theologian who had won wide and deep respect for his work in past decades. Hart, as you might guess, is a universalist. In fact, in recent years he has launched mean-spirited attacks on all traditionally-orthodox (that is, those who accept what traditional orthodoxy has always taught, that there are two final destinations for human beings, not just one) theologians and Christians. In a New York Times op-ed entitled “Why Do People Believe in Hell?” he attributed this belief to the “deep emotional need . . . of being admired when so many are despised, of being envied when so many have been scorned.” This is Hart’s psychological dismissal of the traditional faith of St. Francis of Assisi, Mother Teresa, and billions of other Christians throughout history.

Elsewhere Hart wrote that Christians who think there is an eternal hell are “moral imbeciles” whose traditional understanding of eschatology should inspire us to “only a kind of remote, vacuous loathing.” Note the insult and character assassination of those who disagree with him. Sadly, this is Hart’s stock in trade. McClymond in stark contrast has written of Hart with respect and appreciation for his other theological achievements.

Hart’s review of The Devil’s Redemption is a case-study in defensiveness. He takes aptly-aimed criticisms of his universalism (for instance, that it distorts the biblical and historical record) and throws them back at his critics—with ridicule and lies added for spice. Listen to the ridicule: “This is not scholarship. It is tinfoil-hat-wearing conspiracy theory of the most cartoonish kind.” Here are some of the many lies: “In its short existence, the book has already become something of a joke in certain of the more rarefied academic circles. . . . McClymond simply does not know enough about much of anything that he talks about in its pages. He obviously has next to no grasp of late Graeco-Roman antiquity, or of classical culture, language, philosophy, and religion. Neither, clearly, is he a New Testament scholar.”

Why are these lies? The only rarefied academic circle where The Devil’s Redemption is a joke is the mutually-reinforcing circle of universalists. The jokes among the learned there are nervous jokes because some of them concede that McClymond has built a formidable case. To say that Mike McClymond knows little of antiquity or classical culture and thought is to be unfamiliar with the man and his scholarship and to make a specious claim based on that unfamiliarity. No New Testament scholar? Hart seems to claim he is one because he translated the New Testament, but this does not make one a New Testament scholar (Ronald Knox the Catholic theologian translated the Bible without being a Bible scholar). Yet McClymond produced a highly-regarded monograph on Jesus and the gospels, Familiar Stranger. One can do respected NT scholarship while working primarily in other fields like theology.

Hart’s spiteful accusations would not be worth mentioning if not for the fact that extracts from his malevolent review of The Devil’s Redemption are the first thing that pops up at its Amazon site under Customer Reviews. Readers are told at length that McClymond is incompetent and scurrilous.

So this is the second reason why this book that is destined to become a classic has been largely ignored. Not only does it contradict mainstream theological opinion, but it has been maligned by a venomous universalist whose minions secured a choice spot at Amazon.

Therefore, please do yourself a favor during this Time of the Virus. While you are at home looking for things to occupy your time, order The Devil’s Redemption at Amazon. Treat yourself to a theological education. But don’t think you have to read the whole thing cover to cover. Use it as a reference book for life.

Here you can enjoy marvelously-written reviews of many important philosophers and theologians, from Origen to Maximus the Confessor to Aquinas to Calvin and Barth and Moltmann. Learn about the Gnostic, Kabbalistic, and Esoteric roots of Christian universalism, the German thinkers (Kant, Schleiermacher, Hegel, Schelling and Tillich), Russian thinkers (Solovyov, Berdyaev, Florovsky, and Bulgakov), and more recent trends toward hopeful universalism (de Lubac, Rahner, Teilhard, and von Balthasar). McClymond even analyzes recent evangelical universalists such as Thomas Talbott and Robin Parry.

Enjoy.