Paul F. Bradshaw, The Search for the Origins of Christian Worship

Jewish background

9-10 Bradshaw faults the “organic” approach for its thinking that liturgy develops like biological nature through an evolutionary process. According to this model the earlier is always simpler and the later is more complex. But, Bradshaw argues, liturgy develops not like nature but like culture. There is no inner essence, and there are not overall laws that govern the evolution. This “Comparative Study of Liturgies” is therefore suspect in its methodological assumptions.

[problems with Bradshaw’s criticisms: while he is right to distinguish between biological and cultural development, he himself seems to agree with what he said was a broad scholarly agreement that development usually proceeds from brevity to prolixity (2-3). He also acknowledges that Baumstark, a leader in this Comparative school, saw both developmental tendencies—from early variety to uniformity and vice-versa, and from simplicity to prolixity and vice-versa (11).]15 He proposes a hermeneutics of suspicion for liturgical texts: it is dangerous to read them as verbatim accounts of a liturgical act. Directions usually deal not with the accepted and customary but with new or uncertain or controverted points.

17 Authoritative-sounding statements are not always authoritative. For example, Demetrius, patriarch of Alexandria in the 3rd c., said the unordained never preach, yet the practice was defended by the bishops of Caesarea and Jerusalem.

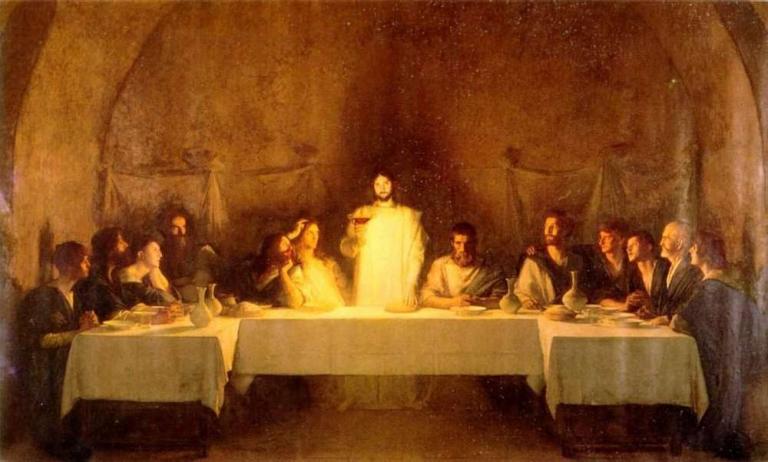

18-19 Liturgical legislation is not always followed, especially if it tried to dislodge a much-loved local custom. If they forbid something, that is good evidence that what was being forbidden was being practiced. E.g., John Chrysostom’s describing those who left the service after communion as resembling Judas Iscariot at the Last Supper.

19 When a variety of explanations is given for a practice, we should not assume that any one is genuine. It may mean that no one knows how that practice started, and each explanation was made up because it supported a local custom.

20 Despite all this historical skepticism, Bradshaw asserts that we can know in a provisional way about how worship began and developed in the first few centuries.

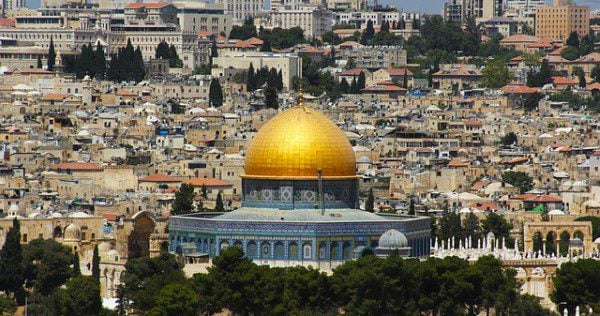

24 Bradshaw says we are much less certain about what was happening in first-century Jewish worship. We used to draw lines from the synagogue and Temple to the early Christian assemblies, but now we are not so sure what those lines were because of the variety of things going on in the synagogues. The basic problem is that our sources date from the 9th and 8th cs AD (Mishna, Tosefta and Talmud), and so we are reading things back into earlier centuries.

25-31 There seems to have been greater variety in Jewish liturgy than had been thought, with no central rabbinic authority, and agreement only on basic elements with freedom on how to express those elements. So, for example, we cannot assume that all the descriptions of worship in Talmud described precisely what was going on rather than the authors’ views of what ought to be done.

33 This opens up the possibility that rules for ritual purity of the first century were not as strict as later rules under Talmud. [So Jesus’ disagreements with some Pharasaic schools might not have meant disagreement with all Pharisees, and might have been in accord with some rabbinic traditions.]

36 A growing number of scholars now doubt that any regular Sabbath liturgy was in place before the third century!

37 Heinemann shows that any uniform cycle of Torah readings (a lectionary) belongs to the realm of fiction.

38 The adoption of daily psalms was not until the 8th c.

40 Yet the twice-daily recitation of the Shema was widely practiced before the destruction of the Temple [70 AD]. Scholars are unsure, however, if the thrice-daily recitation of the Tefillah (Amidah) existed in the 1st c., or was developed later.

44-45 There are variations among Jews from place to place, but there does seem to have been a fairly common practice at meals of saying blessings or thanksgivings for the gift of food and the gift of the Land, and supplications for mercy on the people, the city of Jerusalem, and the Temple.