Paul F. Bradshaw, The Search for the Origins of Christian Worship

Worship in the NT

51-2 Bradshaw claims that there is no unambiguous witness in the NT to a particular liturgical practice. He points to Massey Shepherd’s claim that the Book of Revelation is a full-blown baptismal liturgy, and recent scholars who point out that no standardized paschal initiation liturgy existed anywhere before the 4th c.

52-53 He also claims there is no single, uniform liturgical archetype in the NT, and no single archetype in the post-NT church. Evidence? “Contemporary currents in NT scholarship” that stress the “pluriform nature of primitive Xty.” [my question: Is Bradshaw reading his own preconceptions into the NT?]

53 One of the problems, he argues, is that nearly all explicit references to worship occur in the Acts of the Apostles.

53-54 He asks if Acts gives us what really happened, or the church’s practices of the later first century read into the first generation, or “the author’s own imagination” of what ought to happen? [this is historical skepticism, common in NT scholarship, used now in liturgical studies]

56 The other NT books allude to liturgy without describing it explicitly.

57 “It is generally taken for granted that the early Xns did not use incense in their worship, despite reference to it in Rev. 5.8 and 8.3f.” [Why should we accept this skeptical claim?]

59 Early Xns increasingly used eucharisteo (thanksgiving, associated with Greek Gentile “Hellenists”) instead of eulogeo (the Jewish blessing), thus showing increasing distance from synagogue influence.

60 Matthew 28 contains Jesus’ command to baptize all nations, but Bradshaw finds it difficult to accept this as authentic because “Christian baptisms seem at first to have been ‘in the name of Jesus’ rather than of the Trinity.’” [this historical skepticism, refusing to allow for the possibility of both practices at the same time in non-competitive ways, is outdated and arbitrary]

60n The classic debate over whether the early church baptized infants was primarily between Jeremias and Aland. Good bibliography here.

61 Bradshaw concludes that the process of becoming a Xn was interpreted in a variety of ways, with some traditions emphasizing forgiveness of sins and the gift of the Spirit, others the metaphor of birth to new life, others baptism as enlightenment, and in Paul’s theology union with X thru participation in his death and resurrection. “This variation in baptismal theology encourages the supposition that the ritual itself may also have varied from place to place.” Some places might have used foot-washing instead of whole-body washing, others perhaps used anointing with oil rather than water.

62 Bradshaw argues that there is no firm evidence for an institution narrative in the eucharist ceremony until the 4th c., and then it has the marks of an innovation rather than well-established custom. Prior to that, it was catechical rather than liturgical. [here he agrees with Dix, whose four-fold shape leaves out the institution narrative as a part of every early Eucharist]

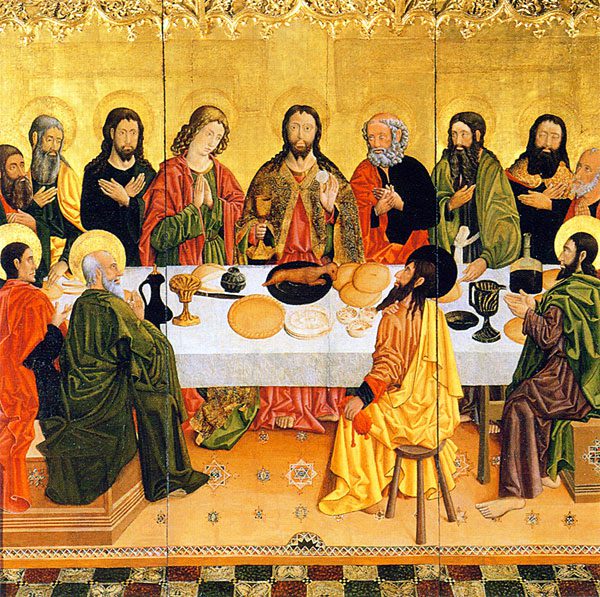

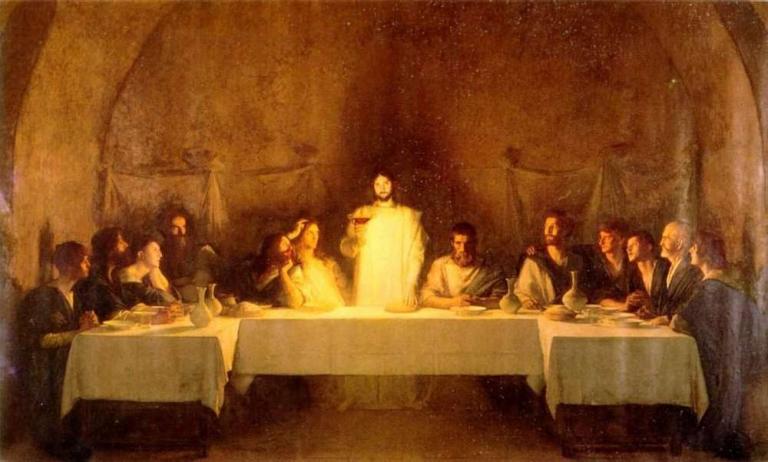

63-64 Scholars have debated whether the Eucharist was a Passover meal, since it is said to be one in the synoptics but not in John. Dix argued that it was a haburah meal (of friendship but invested with religious solemnity), but Jeremias said there is no evidence for such an institution, and that haburah meals were for circumcisions or weddings or funerals. [In Jesus and the Last Supper (2015) Brant Pitre argues that the date in the synoptics and John is the same: the account of Jesus’ final meal begins on the afternoon of 14 Nisan, continues through the night of 15 Nisan, on which there is a Passover meal, and concludes with the crucifixion on 15 Nisan. The key, he says, is to recognize that the term pascha is used variously to refer to the Passover lamb, the larger Passover meal, the Passover peace offering (later in the weeklong festival), and the Passover week as a whole.]

65 Bradshaw claims that even if the Eucharist was a Passover meal, “no exclusively paschal practices appear to have been retained in the primitive Church’s Eucharistic celebrations.” [This is belied by the synoptics and Paul placing the words of institution about Jesus identifying with the bread and wine at the center of the Last Supper, and bread and wine being central to Passover. But far more important are Luke’s words, “Then came the day of Unleavened Bread, on which the pascha had to be sacrificed. So Jesus sent Peter and John, saying, “Go and prepare the pascha for us, that we may eat it.” They said to him, “Where will you have us prepare it?” (Luke 22:7-8) As Pitre argues, the word for pascha undoubtedly refers to the Passover lamb.]

67 Bradshaw argues for a general consensus among scholars that in the earliest Church the eschatological theme (a joyful meal looking forward to the wedding supper of the Lamb) predominated over the memorial theme (remembering the death of Christ), but that the two were joined in the later first century.

68-70 Bradshaw sides with McGowan, who argues that there was great variation in the form of the Eucharist, some ascetic communities replacing wine with water. [this seems a red herring in light of the exclusive use of wine in the NT]

72 Bradshaw insists we must remain “agnostic about many of the roots of Xn worship practices which we observe clearly for the first time in the following centuries.” [My take: while it is certainly true that liturgy developed over the first few centuries and received definitive form in the 4th c., this skepticism toward the NT documents is more reflective of scholarly trends in Bradshaw’s era (the first edition of this book appeared in 1992) than of what many liturgical and NT scholars are willing to say today.]