When did you first discover that other people had more or less than you?

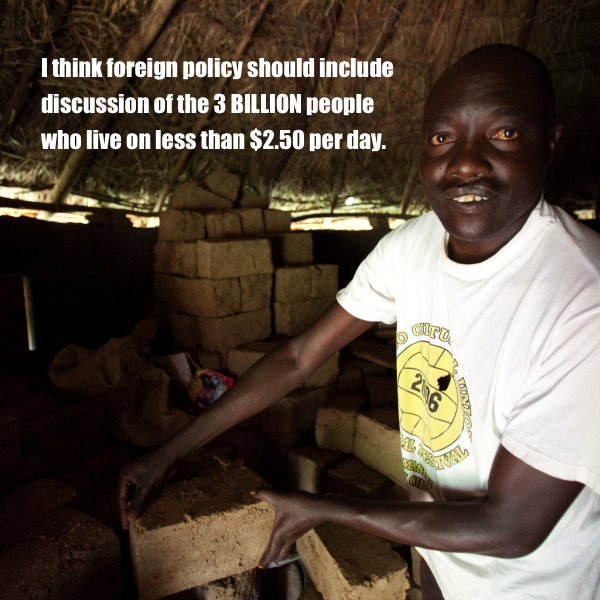

For Maurice, a student in the class I recently taught in Uganda, the moment came seeing another boy kick a stone.

Maurice, a Rwandan, grew up in a rural area going everywhere barefoot. So did every other kid he knew, and nobody saw anything wrong with that. Then one day he was walking along a gravel road and saw a boy walking with his dad. Both wore shoes. The other little boy was kicking a stone along the road. With his sturdy brown shoes, that boy could make a game of kicking a stone.

The boy kicked the stone and it rolled along the road, right up to Maurice’s toes.

His toes touched a stone that would bruise his toes to kick.

“I realized,” he said, “that there are definite differences between people, and I am poor.”

I also have stones I can’t kick.

In writing a chapter for This Ordinary Adventure about the questions of money we faced when we moved back to the U.S., I realized there were two very different problems we in the U.S. middle class face at the same time.

First, we dodge an onslaught of reminders that we, too, are poor. We came back to the U.S. without a couch, a car, a cell phone, or a home. We spent hours making purchasing decisions about every single thing that fills a home. Many things we decided to wait on, to buy second hand, or not to buy at all. We looked around at all the beautifully-filled houses, came home to our little two-bedroom apartment filled with rummage sale deals, and felt very poor.

But at the same time, we know all too well how very wealthy we are. We have known people who don’t wear shoes, people who sleep on boards, people whose families have never owned a bicycle or a horse, much less a car (or our two cars).

We are very rich.

We are so inclined to decide our wealth according to who is standing next to us.

There’s always somebody who wants what you have, and always somebody’s with stuff you want to have. Fostering contentment becomes ever more important in our globalizing world.

Maurice today works with World Relief, an organization that tackles the problem in multiple directions at a time. And he reminds me to use those same strategies in my own life.

For little boys who would love just to have shoes to kick stones down the road, World Relief manages various programs that eliminate the deepest of poverty. And to multiply the effects, they incorporate generosity into the training of recipients of their programs. And so that the boy doesn’t grow up with an ever-insatiable desire for what somebody else has, they teach the biblical truth that true happiness stems from God and not from having stuff.

When do you feel wealthy? When do you feel poor?