On February 21st, I was very fortunate to attend a special event at the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation in London – “The Origins of Shozoku”.

Shōzoku (装束) are garments worn by those involved in Shinto ritual, including priests, miko (“shine maidens”) and performers of ritual music and dance. This talk was led by Hisashi Yoshida, the Director of a Shinto ceremony company that creates traditional Japanese costumes, specialising in professional garments for Shinto priests as well as dressing and creating ritual Shinto ornaments and furnishings. As a professional “emonja” (a dresser of traditional formal garments), Yoshida-san is deeply involved in Shinto festivals throughout Japan.

The evening began in silence. Without a word, Yoshida-san came on stage with a woman dressed in very simple white robes.

This woman was Tokiko Ihara, a performer of a Japanese instrument known as shō (笙). The shō is a wind instrument used in Gagaku, Japanese classical music that has been performed at the Imperial Court in Japan for several centuries. It is also strongly associated with Shinto.

In silence, Yoshida-san began to dress Ihara-san in robes suitable for performing the shō.

The process was slow and meticulous. This particular outfit had a lot of layers.

My interest was piqued by the design of the outer layer – a triskel (or triskelion, triple spiral motif), identical to those seen in Celtic art!

The final touch was the eboshi, or tall cap most often seen on Shinto priests.

Once Ihara-san was robed, the lights were dimmed and she took a seat. She took up her shō in one hand and held it over a heater while she sung in the gagaku style. The shō needs to be heated before playing because any moisture in the pipes will prevent it from being played properly. We were later told that shō heated with an electronic heater like this one sound different to those heated in the traditional method using charcoal.

At last, Ihara-san began to play. I’d heard recorded shō music a few times before, but this was my first time to hear it live. The shō’s sound is unique and spine-tingling. I felt a shiver go through my body the minute the music began. I looked over to a woman near me, and I saw her visibly shiver too! Its sound is so steady and clear that it almost sound like an electronic instrument rather than something from centuries ago. Add to that its ethereal, eerie quality, and it almost feels as if it belongs more in a sci-fi movie rather than an Imperial court! You can hear what the shō sounds like here.

During the performance, I closed my eyes and let the music wash over me. It made me think of bright morning sunlight shining through the trees, or the sun rising over mountain tops – all very Shinto images! I can understand why this music is associated with the spiritual world, and why it is played to honour the kami.

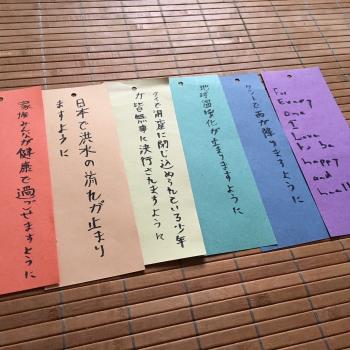

After this performance, it was Yoshida-san’s turn to finally speak about his work. He told us about how shōzoku originated from traditional hunting attire, the wide variety of shōzoku, and the thought that goes into the patterns. He told us that the patterns, while usually originating from traditional Japanese art, can often be found in many other cultures. He also said that in modern times, some shōzoku deliberately incorporate patterns found in European, Islamic and other cultural traditions.

Yoshida-san is worried, though, that the art of making and wearing shōzoku is under threat in modern Japan, as fewer people are skilled in the traditional craft and the demand for these garments is decreasing. He hopes that perhaps people outside Japan may take an interest in shōzoku and come to Japan to learn the tailoring skills. This may be one way to preserve this traditional craft. He touched on the issue of Japan’s secularism – a subject close to my heart! Due to the strict separation of religion and state in Japan, it can be a challenge to receive government support for craft like shōzoku due to its link to Shinto. Therefore, shōzoku must find creative and innovative ways to continue their profession without relying on state support.

I learned that it can take 2-3 months to make a single garment, and that it takes around 20 minutes for two people to dress someone in particularly complex shōzoku (although it only takes about 5 minutes to take off!)

After his talk, Yoshida-san gave us all the opportunity to ask questions. I was particularly curious about the triskel motif on Ihara-san’s robes, so I asked about this. Had they chosen to showcase this particular garment because of the Celtic connection, and because they were currently in the UK?

Yoshida-san and Ihara-san seemed pleased that I’d noticed the design, and Yoshida-san was well aware that the symbol was used in both ancient Celtic and Japanese cultures. It turned out that the two of them had come up with this design together. Ihara-san had requested a design to reflect thunder. Yoshida-san’s research had led him to the designs of Japan’s Jōmon period (designs, and there he came upon the spiral design which apparently may represent thunder.

I was really grateful to Yoshida-san and Ihara-san, and to the Daiwa Foundation, for giving us all this extremely rare opportunity to experience peripheral aspects of Shinto culture in London. It was also particularly meaningful to see the Shinto garments combined with a performance of Shinto music. It really put them both into context and helped us all get a better feeling of the spirit of Shinto and the mysterious force of kami.