A friend of mine once asked me “Why do Pagans spend so much time obsessing about Christianity?” It’s a fair question, and one I have numerous answers to. The most obvious answer is that Christianity is the dominant religion in our society and culture, and to not acknowledge it is akin to ignoring a pink elephant sitting in your living room. Nearly every aspect of our society is filtered through the prism of Christianity in some respects. Christian Morality has decided what is legal and illegal in our society, what is “moral” and what is not, and what can and cannot be said on television.

A friend of mine once asked me “Why do Pagans spend so much time obsessing about Christianity?” It’s a fair question, and one I have numerous answers to. The most obvious answer is that Christianity is the dominant religion in our society and culture, and to not acknowledge it is akin to ignoring a pink elephant sitting in your living room. Nearly every aspect of our society is filtered through the prism of Christianity in some respects. Christian Morality has decided what is legal and illegal in our society, what is “moral” and what is not, and what can and cannot be said on television.

It’s also the faith that many of us Modern Pagans were raised in. Since it was such a part of my early life, I’m still curious about it. My reasons for writing about it are not to disprove it, but to figure out why certain things were written in certain ways. Understanding the context of it leads to a better understanding of it. I just wish that line of thinking was shared by more Christians, many of whom blindly accept every statement in their Bibles at face value, without evaluating the context or circumstances under which it was written.

From a purely personal stand-point I enjoy reading about the origins of Christianity because I find value in the stories (I think Christianity can make someone a better person), and because its history is interesting to me. I’m not sure when Pan became a god exactly, but you can make the argument that we know the day when Jesus’ divinity was voted on. Christianity is young enough, and with enough of a paper trail, that it’s easy to mark major moments in its development. While I’m mostly concerned about the histories of my own faith, I’m a student of religious history in general.

Nothing in this essay is ground breaking, but our media has trouble portraying the birth of Jesus in any way outside of the gospel narratives. It bothers me that a story so full of holes historically never gets called out on the problems inherent within it. Every Christmas I run into cable television documentaries out to prove the historicity of Matthew and Luke, with very few offering competing viewpoints. Periodically “scholars” will host these crazy quests for magical stars that exist only in myth. If the “liberal media” isn’t going to bother to tell the truth about what the gospels (and history) say and don’t say about the birth of Jesus, it becomes necessary for twits like myself to do it.

I’ll also admit to genuinely enjoying the story of the nativity and the imagery behind it. It’s colorful and it dovetails quite nicely around my own holiday mythology. I’ve always seen the Pagan Wheel of the Year as an annual celebration of both life and death, and in that mythology the Lord of the Sun dies at Samhain to be reborn at Yule. I don’t think he’s reborn in a manger every year, but the portrayal of the whole enterprise is similar enough that when I see pictures of a nativity scene I’m filled with positive thoughts instead of negative ones.

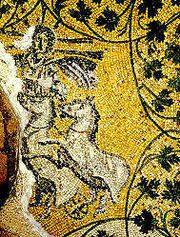

It’s easy to try and claim Jesus as a solar deity, though a little bit dishonest intellectually. His early Jewish followers certainly didn’t see him that way, nor did the Apostle Paul. It’s certainly likely that individuals more removed from theology did, and there are even images of Jesus driving a solar chariot. The lines between gods have a tendency to blur, and instead o being angry when I see a Nativity scene the far easier thing to do is it view it as the birthplace of Apollo or Sol Invictus.

It’s easy to try and claim Jesus as a solar deity, though a little bit dishonest intellectually. His early Jewish followers certainly didn’t see him that way, nor did the Apostle Paul. It’s certainly likely that individuals more removed from theology did, and there are even images of Jesus driving a solar chariot. The lines between gods have a tendency to blur, and instead o being angry when I see a Nativity scene the far easier thing to do is it view it as the birthplace of Apollo or Sol Invictus.

While I don’t necessarily “believe” in every religion out there, I can still acknowledge an “awe moment” in other faiths. I have no great interest or passion for Islam, but watching Muslims congregate at the Ka’ba in Mecca fills me with a sense of wonder. I feel the same way when I witness religious rites in Bethlehem on Christmas Eve. I don’t believe that Jesus was literally born in that particular space, but there’s power there because people have believed in it for so long. I can be moved by the faith of others even when it’s not my own. Such as it is with the Nativity.

The New Testament says very little about the birth of Jesus. The earliest writings in the New Testament, letters from the Apostle Paul, make no mention of Jesus’ birth. The authentic* letters of Paul were written in about 50 BCE, twenty years or so after the crucifixion. Had their been a miraculous story surrounding Jesus’ birth you’d think Paul would have mentioned it, but alas, there are no tales of Wise Men, virgin births, shepherds, or even Bethlehem.

The earliest gospel, Mark, doesn’t mention the birth of Jesus either. Again, this is odd if wondrous things were happening that day. Mark’s gospel begins with Jesus being baptized by John the Baptist and the start of his public ministry, anything before that is irrelevant to the writer of Mark. Mark’s attitude seems to summarize the thoughts of early Christians pretty well, the birth of Jesus wasn’t important, it was the death of Jesus that mattered.

The Gospel of John was the last of the canonical gospels to be written, dating to sometime between 90 and 100 CE. The writer of John skips the familiar Christmas story we all grew up with too. John does kind of write a birth narrative, but it’s a cosmic narrative (dare I say gnostic at times?), and has nothing in common with the Jesus Birthday stories we know so well.

When it comes to the actual story of Jesus’ birth, there isn’t one, there are two. The story of Jesus’ birth is laid out in the gospels of Luke and Matthew, but the stories are incredibly different. The Christmas Pageants we grew up with in church (and possibly public school as well) are a combination of the two stories, with some additional material thrown in. Probably due to “Merry Christmas Charlie Brown!” on TV, I’m more familiar with the version presented in Luke than the one in Matthew, so I thought I’d start there.

Luke’s account is exceedingly brief, just eight to ten paragraphs (and a nice poem attributed to Mary) depending on whatever translation one is reading. Luke spends more time talking about Mary’s pregnancy and her visit from the angel Gabriel than he does the actual birth of Jesus.

The second chapter of Luke relates the parts of the Nativity story most people are familiar with. There are angels, shepherds, a manger, Bethlehem, and no room at the inn. Those are about all the details Luke provides. His story hints at a time of year (shepherds usually got the winter months off), but that’s it for detail. As early as Junior High I remember being incredibly disappointed with how little information there was in the Bible about the birth of Jesus. I always expected that particular “Bible Study” to last the entire month of December, not twenty minutes.

The second chapter of Luke relates the parts of the Nativity story most people are familiar with. There are angels, shepherds, a manger, Bethlehem, and no room at the inn. Those are about all the details Luke provides. His story hints at a time of year (shepherds usually got the winter months off), but that’s it for detail. As early as Junior High I remember being incredibly disappointed with how little information there was in the Bible about the birth of Jesus. I always expected that particular “Bible Study” to last the entire month of December, not twenty minutes.

Luke’s version of events reads as it does because he was writing to Gentiles, and probably peasant gentiles at that. His concern is not with establishing Jesus as an earthly king-like messiah, he was concerned with portraying Jesus as humble and accessible. Sure he’s a bit worried about Jewish prophecy, but as the author** wasn’t Jewish it’s not a major issue to him.

Luke does give some historical context to his story, the most famous of which is a census allegedly taken at the time of Jesus’ birth. “At that time Emperor Augustus ordered a census to be taken throughout the Roman Empire. When this census took place, Quirinius was the governor of Syria. Everyone then went to register himself, each at his home town.” Here the author of Luke cites a specific event and a verifiable historical personage, but both references have serious problems.

The reign of Caesar Augustus is pretty well documented, and there’s not a piece of paper anywhere outside of the Gospel of Luke that tells of an Empire wide census. The census is simply a vehicle to get Joseph and Mary to Bethlehem, where, according to Jewish Prophecy, the messiah is supposed to be born. There is no way that this census was an actual historical event, it was simply a literary device.

If you really stop to think about the census and each person registering “at his home town” you come up with a snarl of near epic proportions. Joseph went to Bethlehem because his ancestor of one thousand years ago was King David (the record keeping for a guy who ended up as a humble carpenter is amazing!). If every person in the Roman Empire had to trace their lineage back one thousand years and then go to that ancestors hometown in an era of foot-travel . . . . commerce and trade would literally halt, armies would fall apart, and the whole giant enterprise would be commented on outside of a sentence in Luke.

Luke’s reference to Quirinius is also curious. Quirinius was the governor of Syria, but he did not become the governor of Syria until 6 CE. The date is troubling because the writer of Matthew states in no uncertain terms that Herod was the King of Judea when Jesus was born. Unfortunately that’s not possible since Herod died ten years before Quirinius took the throne. If Luke’s references to the census and Quirinius are wrong (and history tells us they are), everything else in his birth narrative might be wrong as well. (1)

Where as the story presented in Luke is rather salt of the earth, the story presented in Matthew is far more royal. In Matthew it is Joseph who gets a heavenly visit, not Mary. The writer of the gospel also takes pains to point out that Jesus being born of a virgin is a fulfillment of a prophecy found in the book Isaiah.

There are some serious problems with that prophecy in Isaiah, and the writer of Matthew may have completely misunderstood what he was reading. In the Hebrew, Isaiah uses the word “alma” which can certainly mean virgin, but it more accurately translates to “young woman.” Most babies born in the year 3 (or 4) BCE were born of young women, there’s nothing all that miraculous about that. Coupled with the silence from Mark and Paul, it’s unlikely that Jesus was born of a virgin (not to mention the difficulty), it’s also unlikely that Isaiah meant to have his prophecy interpreted that way.

There are some serious problems with that prophecy in Isaiah, and the writer of Matthew may have completely misunderstood what he was reading. In the Hebrew, Isaiah uses the word “alma” which can certainly mean virgin, but it more accurately translates to “young woman.” Most babies born in the year 3 (or 4) BCE were born of young women, there’s nothing all that miraculous about that. Coupled with the silence from Mark and Paul, it’s unlikely that Jesus was born of a virgin (not to mention the difficulty), it’s also unlikely that Isaiah meant to have his prophecy interpreted that way.

It’s Matthew, and Matthew only, who tells the tale of the “Visitors From the East” (as they are called in my Good News Bible). The Three Wise Men as we call them today were never named in Matthew, he doesn’t even tell you how many there are. The idea that there were three, and that they had names, was a much later invention. Matthew simply says they were from the East and attended the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem after following a star. Matthew’s Jesus is also born in a house, and there are no mentions of a manger or problems with the local inns. “They went into the house” is how my Bible puts it.

One of the most amazing miracles in the Gospel of Matthew is the Star of Bethlehem, and for centuries now scholars have scoured the sky looking for some sort of celestial event in order to explain Matthew’s star. They’ll never find the proof they are looking for because “The Star” is simply part of a story, designed to emphasize the idea that the birth of Jesus is special and different. I’ve never understood the obsession with trying to verify the Star of Bethlehem as an actual historical event. It’s a matter of faith and belief, it’s not a matter for science. I think you are just as likely to find Rudolph’s nose in the sky as you are the Star of Bethlehem.

One of the most amazing miracles in the Gospel of Matthew is the Star of Bethlehem, and for centuries now scholars have scoured the sky looking for some sort of celestial event in order to explain Matthew’s star. They’ll never find the proof they are looking for because “The Star” is simply part of a story, designed to emphasize the idea that the birth of Jesus is special and different. I’ve never understood the obsession with trying to verify the Star of Bethlehem as an actual historical event. It’s a matter of faith and belief, it’s not a matter for science. I think you are just as likely to find Rudolph’s nose in the sky as you are the Star of Bethlehem.

Like Luke, Matthew makes reference to an historical event that we should be able to find evidence for. In this case that event is the “Massacre of the Innocents.” The Massacre of the Innocents is Herod’s attempt to kill Jesus, the “King of the Jews,”after being made aware of his impending birth by the Wise Men. The Massacre involved the killing of every male in the area in and around Bethlehem under the age of two, and it’s only mentioned in the Book of Matthew. You’d think such a horrible event would be documented in at least a few other places. (Thankfully, the Massacre of the Innocents did not end up as one of the Twelve Days of Christmas.)

In recent years it’s become popular in modern Pagan circles to claim that all of the “story” surrounding the birth of Jesus is pagan in origin. I think some of that’s true. Pagan myth is probably partially responsible for the idea that Jesus was born of a virgin, and it explains things like the stars and the magi. Superhuman characters often have superhuman birth narratives, Jesus is much like Dionysus or Osiris to that effect. That doesn’t mean that Jesus was created out of thin air to become sort of pagan dying and resurrecting god-man, just that supernatural elements were added to his story in the decades after his death. Similar tales are told of Cesar Augustus, the only difference is that people don’t take those so literally.

Christmas was an unknown holiday in the early Christian Church. Jewish holidays and then Easter took center stage. Birthday holidays were considered pagan by early Church leaders like Origen. Some of his quotes on the subject are pretty scathing on the subject. He was once wrote that saints “not only do not celebrate a festival on their birth days, but filled with the Holy Spirit, they curse that day.” Ouch. Origen certainly didn’t put a stocking up on Christmas Eve.

While Christians began celebrating “Christ’s Mass” in the Third Century, there was no consensus on the date. Those early versions of Christmas would have been unfamiliar to the majority of us too. It wasn’t until the Fourth Century in 354 CE that December 25th was finally settled on as the birthday of Jesus. The trappings that we associate with the holiday would emerge from pagan celebrations like Saturnalia and the Kalends. (2) I don’t write about the Nativity to condemn, I write to share an understanding of it. It’s a story we think we known, and yet our understanding of it is an amalgamation of Luke, Matthew, and other mythologies.

I’ve used more words in this post about the birth of Jesus than the writers of Matthew and Luke did 1900 years ago. I think their lack of words is a major reason why the story of Jesus’ birth has resonated with so many people over the centuries. Those gospel writers provided so little information that it was easy to insert things into the narrative. Their lack of detail has allowed people to share the story in ways that they see as beneficial. It’s how we ended up with Little Drummer Boys and talking donkeys. As a slice of history the Nativity is lacking, but it’s a wonderful slice of mythology.

I’ve used more words in this post about the birth of Jesus than the writers of Matthew and Luke did 1900 years ago. I think their lack of words is a major reason why the story of Jesus’ birth has resonated with so many people over the centuries. Those gospel writers provided so little information that it was easy to insert things into the narrative. Their lack of detail has allowed people to share the story in ways that they see as beneficial. It’s how we ended up with Little Drummer Boys and talking donkeys. As a slice of history the Nativity is lacking, but it’s a wonderful slice of mythology.

*Out of the the thirteen (or fourteen if you count Hebrews) letters attributed to Paul, only seven of those are seen as authentic by a majority of scholars.

**It’s extremely unlikely that Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John wrote the gospels that bear their names. Those names are more a product of tradition than any real facts. None of the canonical gospels contain anything stating who wrote them. I sometimes will use phrasing such as “Luke does” or “Luke wrote” for the sake of clarity.

A note on sources . . . .

There’s nothing in this piece all that revolutionary, and all the information here is pretty standard stuff and can be found in any serious, scholarly account of the New Testament.

1. Jesus, Interrupted: Revealing the Hidden Contradictions in the Bible (and Why We Don’t Know About Them) by Bart D. Ehrman. Harper Collins Publishing, 2009, pages 29-35.

Jesus, Interrupted is one of clearest, most concise books I’ve come across detailing the inconsistencies found in the Bible (specifically the New Testament). It also contains a lot of information about who wrote what in the New Testament and why. It lacks a lot of depth, but is a great introduction to the topic. The Daily Beast is currently running a piece written by Ehrman addressing many of the things I’ve written here.

2. The Origins of Christmas by Joseph F. Kelly. Liturgical Press, 2004 pages 63-71.

I’m so incredibly biased I’m essentially using a Catholic Press as source material. Kelly’s book is almost entirely about the Nativity and the gospel accounts of Jesus’ birth. It’s short, contains nearly all the relevant information, and doesn’t get bogged down in scholar speak.