(This post is the first in a series based upon a lecture I began presenting this past Spring. That talk, “Magick and The Occult in America 1820-1952” surveys a large swath of American History and the occult and magickal practices contained within it. None of this is meant to be the last or only word on the subject, it’s just a look into corners of history I find particularly interesting. The actual lecture has more information than the written versions (and usually more jokes!) but I wanted to present at least some of that talk here on Raise the Horns. -jason)

(This post is the first in a series based upon a lecture I began presenting this past Spring. That talk, “Magick and The Occult in America 1820-1952” surveys a large swath of American History and the occult and magickal practices contained within it. None of this is meant to be the last or only word on the subject, it’s just a look into corners of history I find particularly interesting. The actual lecture has more information than the written versions (and usually more jokes!) but I wanted to present at least some of that talk here on Raise the Horns. -jason)

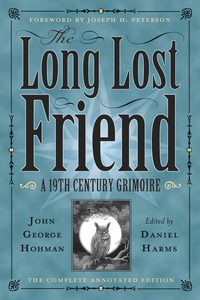

My interest in The Long Lost Friend began after reading the book Grimoires by Owen Davies. Davies only makes a few quick references to The Friend, but they were enough to etch the name into my brain. Last summer I found myself in New York City for an outdoor Pagan event at a local park near 5th Avenue. Not wanting to use the public bathrooms at that park I hiked over to the nearby Barnes & Noble to do my business. Since I was in a bookstore I couldn’t help but scan the New Age/Magickal Arts section. Most of it was the standard Pagan stuff that I see at most bookstores, except for one slim blue volume . . . . . Scattered amongst the Ravenwolfs, Penczaks and Grimassis was an updated edition of The Long Lost Friend, recently edited by Daniel Harms and complete with a lengthy (and scholarly) introduction. Jackpot!

One of the most interesting things about The Friend is that it was a huge bestseller in its own time, and still probably holds the record for bestselling “American grimoire.” For all of the copies that it sold it’s now a relatively forgotten piece of Americana, but it shouldn’t be. The Friend has had a great deal of influence on many different occult traditions. You can find spells from The Long Lost Friend in Hoodoo and Santeria, and though I don’t know this for sure, I’m sure that at least a few American Witches have used spells from The Friend as well. This is an important book and it prompted me to put together a workshop about the occult in America. This piece is an excerpt from that workshop, and was “written” via Dragon Dictate so it reads a little differently than most of my stuff here on Raise the Horns.

One of the most interesting things about The Friend is that it was a huge bestseller in its own time, and still probably holds the record for bestselling “American grimoire.” For all of the copies that it sold it’s now a relatively forgotten piece of Americana, but it shouldn’t be. The Friend has had a great deal of influence on many different occult traditions. You can find spells from The Long Lost Friend in Hoodoo and Santeria, and though I don’t know this for sure, I’m sure that at least a few American Witches have used spells from The Friend as well. This is an important book and it prompted me to put together a workshop about the occult in America. This piece is an excerpt from that workshop, and was “written” via Dragon Dictate so it reads a little differently than most of my stuff here on Raise the Horns.

The story of The Long Lost Friend begins with its author John George Hohman. Hohman was a German immigrant who settled with the mostly Lutheran and German speaking Pennsylvania Dutch. Hohman worked his way over to the young United States as an indentured servant, traveling with his wife and baby. Before writing The Friend Hohman released several other magical books similar to his magnum opus. My favorite of those books was entitled The Land and House Medicine Chest or True and Thorough Lessons for the Farmer and Town Man Containing the Very Best Remedies for Both Man and Animals, also Horses. (Apparently horses aren’t “animals” and exist in their own little world). Also Horses was published in 1816. (1)

The Long Lost Friend was released shortly thereafter in 1820 and was the last magical book written by Hohman (though he may have overseen an English edition of The Friend in 1846). He died 25 years after the publication of The Friend at age 66 . While he was hopeful that The Friend would earn him lots of money, it did not. Hohman was poor for most of his life, and even had his possessions repossessed one sad Christmas Eve. He did however continue to write for his entire life but mostly songs and ballads after the publication of The Friend.

The Long Lost Friend is an example of “House Father Literature” a German genre designed to help the landowner of limited financial means. House Father Books were not simply collections of spells, they also contained herbal cures and home remedies to deal with sickness. There were tips for dealing with farm issues and sometimes the weather. Some House Father Books contained spells and charms, but most did not. Often spells were written by hand into these types of books and then handed down. Some of those “spells in the margins” were even written in a kind of cipher. House Father Books, and the spells sometimes contained within them, were then passed down and became mainstays of Pennsylvania Dutch healing practices.

The Long Lost Friend is an example of “House Father Literature” a German genre designed to help the landowner of limited financial means. House Father Books were not simply collections of spells, they also contained herbal cures and home remedies to deal with sickness. There were tips for dealing with farm issues and sometimes the weather. Some House Father Books contained spells and charms, but most did not. Often spells were written by hand into these types of books and then handed down. Some of those “spells in the margins” were even written in a kind of cipher. House Father Books, and the spells sometimes contained within them, were then passed down and became mainstays of Pennsylvania Dutch healing practices.

Isolated because of language barriers, the spells and practices in those books were very important to the Pennsylvania Dutch. Healers using those practices became known as braucherei (singular braucher) from the German word “to try.” The practices of the braucherei were not isolated to early America either. The brucherie continue to practice their arts today. Later this practice became known as Pow-Wowing or Pow Wow as an homage to Native American healing techniques, though there is very little, if any, Native American traditions within Pow Wow.

While the braucherei use magick and Hohman’s book is full of charms and spells, neither of them is Pagan. Hohman was a practicing Catholic, though a Catholic very familiar with the traditions of the Lutheran Church. Hohman wraps The Long Lost Friend in Christian clothing, and made pains to do so. Coleman even places the existence of his book in the hands of God by writing “ if God didn’t want this information shared . . . . “ While a deeply Christian book, many of the religious references are garbled. Spells talk about Jesus being born in Jerusalem and how he later crossed the Red Sea during his ministry. It also contains a spell involving the prophet Daniel, baby Jesus and the apostle Paul. Apparently The Long Lost Friend has the power to cut across time and space.

While the braucherei use magick and Hohman’s book is full of charms and spells, neither of them is Pagan. Hohman was a practicing Catholic, though a Catholic very familiar with the traditions of the Lutheran Church. Hohman wraps The Long Lost Friend in Christian clothing, and made pains to do so. Coleman even places the existence of his book in the hands of God by writing “ if God didn’t want this information shared . . . . “ While a deeply Christian book, many of the religious references are garbled. Spells talk about Jesus being born in Jerusalem and how he later crossed the Red Sea during his ministry. It also contains a spell involving the prophet Daniel, baby Jesus and the apostle Paul. Apparently The Long Lost Friend has the power to cut across time and space.

The Friend consists mainly of three different types of “charms” or activities. The first involves natural remedies and is not so different than people eating (or slurping) chicken soup today when they have a cold. The second charms involves the use of natural magick, something which is probably very familiar to most Modern Pagans. For example, putting a specific herb under your pillow to ensure good dreams is an example of natural magic. The third activity found in The Friend are actual spells where the words or hand motions of the conjurer affect a particular outcome. Many of the spells contained in The Friend contain religious references.

The original German publication of The Friend in 1820 contained 190 different charms. While Hohman is credited as the author of those 190 charms, he was more of an assembler as the contents of his book came from many different sources. The majority of the spells in The Friend come from The Romanusbook, a German spell-book first published in 1788. Hohman also used The Book of Aggregations by Albertus Magnus, a 13th Century German Theologian. Some of the spells found in The Friend are unique to it, and were either made up by Hohman, or more likely, come from the folk magick traditions of the Pennsylvania Dutch. Mundane sources for The Friend also include The Complete Herb Book published in 1744, and a charm submitted to the State Senate of Pennsylvania in 1802.

The original German publication of The Friend in 1820 contained 190 different charms. While Hohman is credited as the author of those 190 charms, he was more of an assembler as the contents of his book came from many different sources. The majority of the spells in The Friend come from The Romanusbook, a German spell-book first published in 1788. Hohman also used The Book of Aggregations by Albertus Magnus, a 13th Century German Theologian. Some of the spells found in The Friend are unique to it, and were either made up by Hohman, or more likely, come from the folk magick traditions of the Pennsylvania Dutch. Mundane sources for The Friend also include The Complete Herb Book published in 1744, and a charm submitted to the State Senate of Pennsylvania in 1802.

While The Long Lost Friend wasn’t an economic triumph for Hohman it did become a mainstay of many Pennsylvania Dutch communities. Within a few years of its publication it could be found as far south as South Carolina. The first English edition of the book was published in 1846, and by that date several German editions had also been published. Some of those German editions were attributed to Albert Magnus, and were most likely printed without the consent of Hohman.

Many of those later editions of The Friend also contained new charms added by the individual publishers. In the year 1900 Pow Wows was added to the title of The Long Lost Friend, and to many that’s the name its best known by. One of the most influential versions of The Friend was published in 1924 by the LW de Laurence company, a publisher that often flaunted copyright laws. (You can bet that the descendants of Hohman weren’t making a dime from the de Laurence edition.) What’s most important about the de Laurence edition is that it introduced a completely new audience to The Friend. The products of the de Laurence company were often marketed to African-Americans, which helps to explain how charms from The Friend ended up in the traditions of Hoodoo and Santeria. (The reach of the the de Laurence catalogs was global in scale, and spells from The Friend can also be found in Africa. It was also illegal in Jamaica for several decades.)

Many of those later editions of The Friend also contained new charms added by the individual publishers. In the year 1900 Pow Wows was added to the title of The Long Lost Friend, and to many that’s the name its best known by. One of the most influential versions of The Friend was published in 1924 by the LW de Laurence company, a publisher that often flaunted copyright laws. (You can bet that the descendants of Hohman weren’t making a dime from the de Laurence edition.) What’s most important about the de Laurence edition is that it introduced a completely new audience to The Friend. The products of the de Laurence company were often marketed to African-Americans, which helps to explain how charms from The Friend ended up in the traditions of Hoodoo and Santeria. (The reach of the the de Laurence catalogs was global in scale, and spells from The Friend can also be found in Africa. It was also illegal in Jamaica for several decades.)

Unlike most spell books The Long Lost Friend began to acquire a peculiar reputation. The book itself was said to have power and its presence was said to be necessary for one of its spells to be effective. There were also whispers that simply owning a copy of the book would result in crows roosting on the owner’s roof, with one of those crows being a transformed which. People also talked of passing the book through fire without it being harmed in any way. In the book’s introduction Hohman makes the claim that keeping the book on one’s person prevents physical harm. Devotees of the book would later claim that he was right. In the early 20th century when anthropologists and folklorists first began asking about the book in Pennsylvania Dutch communities few people would admit to owning it, and in the homes that did possess a copy it was generally kept from public view.

Though The Friend is not a pagan book, there are several spells within it that date back to pagan antiquity. Charm 33 instructs the user to write down the following words/letters on a white piece of paper before inserting them into a piece of linen which is then hung from the neck to rid oneself of a fever:

A b a x a C a t a b a x

A b a x a C a t a b a x

A b a x a C a t a b a

A b a x a C a t a b

A b a x a C a t a

A b a x a C a t

A b a x a C a

A b a x a C

A b a x a

A b a x

A b a

A b

A

If the first word in that sequence looks familiar your instincts are right. It’s a corrupted form of “abracadabra” a magickal word whose use dates back to at least 212 CE.

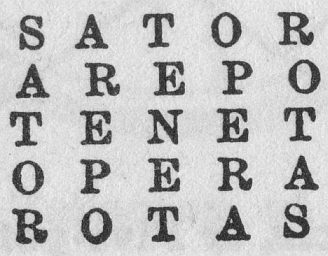

Abracadabra isn’t the only spell from antiquity to be found within The Friend, it also advocates the use of the Sator Square, a magikal formulation that can be found as early as the First Century CE. Charm 123 calls for writing a Sator Square on each side of a plate and then throwing that plate into a fire if you want to easily extinguish a blaze. Scholars have hypothesized that the words on a Square are meant to signify “Alpha and Omega.” Charm 148 suggests writing a Sator Square down on a piece of paper and then feeding it to cattle to protect against witchcraft.

Abracadabra isn’t the only spell from antiquity to be found within The Friend, it also advocates the use of the Sator Square, a magikal formulation that can be found as early as the First Century CE. Charm 123 calls for writing a Sator Square on each side of a plate and then throwing that plate into a fire if you want to easily extinguish a blaze. Scholars have hypothesized that the words on a Square are meant to signify “Alpha and Omega.” Charm 148 suggests writing a Sator Square down on a piece of paper and then feeding it to cattle to protect against witchcraft.

The Long Lost Friend is overlooked by many, but it’s influence on the magickal traditions of the United States (and beyond) is immense. I’m hopeful that the recent release of the Harms edition, along with people like me writing about it, will help to awaken interest in this curious and vital piece of Occult Americana. If you are interested in purchasing a spell book, I’d like to recommend one that has been in print for nearly two hundred years . . . . . . . . .

Pictures:

1. The tag picture for this series of posts.

2. An early edition of The Friend.

3. The Daniel Harms edition just released last year.

4. A classic English title page

5. Albert Magnus

6. LW de Laurence, that guy deserves his own post one of these days.

7. A Sator (or Opera) Square, and you thought musicals weren’t magickal.

There are other bits in this series, including write-ups of Albert Pike and Joseph Smith of the Church of Latter Day Saints. While not originally a part of this series the lecture included material on Johnny Appleseed who I have written about previously. It also included a section on The Church of Aphrodite which Aidan Kelly wrote about last year. (As this was initially posted while on the road, depending on when you are reading this, those links may or may not work.)

_____________

1. The Long Lost Friend by John George Hohman edited by Daniel Harms from Llewellyn Publications and published in 2012. This is where to start, and the introductory material offered by Harms at the beginning of the book is outstanding. There’s a biographical sketch of Hohman, information on Hohman’s sources, background information on the Pennsylvania Dutch . . . tons of great information and it’s all written in an easily accessible style. People pick on Llewellyn a lot, but they deserve a ton of credit for printing this edition of The Friend.

Nearly all the information in this essay comes from Harm’s introduction to the latest edition of The Friend. I can’t recommend it enough. Since this was originally a lecture, and I was running on a deadline, I didn’t have time to do all the footnotes.

2. Grimoires: A History of Magic Books by Owen Davies published by Oxford University Press and originally released in 2009. According to History Today Davies’ Grimoires is “excellent and nuanced,” I probably would have used the phrase “kick ass” but what we both agree on is that it’s a fantastic book and should be on the bookshelves on anyone with a serious scholarly interest in magick or the occult. That particular factoid pops up on page 195.