A few weekends ago at an extensive photo shoot* with some friends I ended up in a discussion about the word “pagan.” It was a mostly congenial chat but it took a nasty turn when I mentioned something about Morris Dancing not being an ancient pagan tradition but a practice that felt pagan** none the less. The moment those words left my mouth a member of our party informed me that I was completely incorrect (and that it was one of the reasons she’s not a Raise the Horns reader).

A few weekends ago at an extensive photo shoot* with some friends I ended up in a discussion about the word “pagan.” It was a mostly congenial chat but it took a nasty turn when I mentioned something about Morris Dancing not being an ancient pagan tradition but a practice that felt pagan** none the less. The moment those words left my mouth a member of our party informed me that I was completely incorrect (and that it was one of the reasons she’s not a Raise the Horns reader).

For the record, my information was correct; Morris Dancing is simply not an ancient pagan practice. It began as a court dance in the Fifteenth Century before eventually moving into the countryside and becoming a dance of the common folk a few decades later. In the early 1900’s several individuals began to argue that Morris Dancing was a pagan practice, most notably Sir James Frazier (author of The Golden Bough) and musician/music collector Cecil Sharp. Up until the 1970’s Morris as pagan was simply accepted as gospel truth, even though the idea had been widely dismissed in academic circles. (1)

Sadly, if I had been allowed to complete my original thought, we probably would have come to an understanding that afternoon, but it was not to be. Morris Dancing might not be an ancient pagan dance, but it’s obviously a dance that resonates with many Modern Pagans, and certainly feels Pagan. I was up at an hour not generally suited for goatboys this past Beltane to watch a few local Morris teams and it was wonderful. The dances may not have stretched back to pagan antiquity, but they still gave voice to my own (Pagan) feelings. In the book Electric Eden author Rob Young describes Morris Dancing in near ecstatic terms:

Sadly, if I had been allowed to complete my original thought, we probably would have come to an understanding that afternoon, but it was not to be. Morris Dancing might not be an ancient pagan dance, but it’s obviously a dance that resonates with many Modern Pagans, and certainly feels Pagan. I was up at an hour not generally suited for goatboys this past Beltane to watch a few local Morris teams and it was wonderful. The dances may not have stretched back to pagan antiquity, but they still gave voice to my own (Pagan) feelings. In the book Electric Eden author Rob Young describes Morris Dancing in near ecstatic terms:

“To those that actually practise (sic) it, morris dance has an elemental quality, an ancient ritual magic comparable to the whirling dervish dance of Sufism, the Native American ghost dance or the spiritual movements developed by G.I. Gurdjieff. Its gestures are designed to act as a lightning conductor for spiritual energies to unite the universe with the earth and replicate the seasonal cycles of growth, death, and rebirth. Morris dancers’ tatter jackets act as symbolic antennae; clogs dash against the ground, awakening slumbering earth gods . . . . .”

While Morris may not be pagan in the sense my friend wanted it to be, it is pagan in a different sense. It’s a great example of what I like to call rustic paganism.

Morris dancing feels pagan because it contains echoes of an earlier era and, in the minds of many, holds a fixed spot on the Wheel of the Year. We associate Morris with Beltane, and that association makes it feel like a seasonal tradition. It’s true that ancient pagans celebrated a holiday in early May. That doesn’t mean all the customs practiced on that day are pagan, but it’s an easy assumption to make. I’m of the opinion that human beings have a deep psychological need to connect with the world around them regardless of religion. The trappings of most major Christian holidays reflect seasonal changes, and while some of them do come from ancient pagan sources, the majority do not, but all kinds of people believe they do.

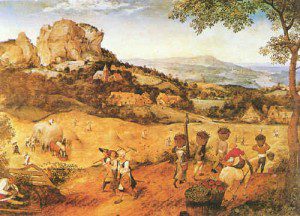

Agricultural celebrations (and their mementos) are not always pagan in a religious sense, but they are a pagan in the way they feel. When writing about Pagan Music I often add the caveat that something is Pagan when it feels Pagan. The celebration of bread that many of us observe at Lammas began as a Christian rite, but works perfectly within a Pagan worldview. It’s a connection to nature and that idea of the golden, eternal countryside where everyone lives in harmony with the Earth. It’s pagan in the sense that being one with nature is pagan, and it’s an association that even many of our critics make. Perhaps the classical definition of pagan as a person of the countryside still has some resonance.

Agricultural celebrations (and their mementos) are not always pagan in a religious sense, but they are a pagan in the way they feel. When writing about Pagan Music I often add the caveat that something is Pagan when it feels Pagan. The celebration of bread that many of us observe at Lammas began as a Christian rite, but works perfectly within a Pagan worldview. It’s a connection to nature and that idea of the golden, eternal countryside where everyone lives in harmony with the Earth. It’s pagan in the sense that being one with nature is pagan, and it’s an association that even many of our critics make. Perhaps the classical definition of pagan as a person of the countryside still has some resonance.

When asked about their favorite season a lot of Modern Pagans tend to reply with Halloween/Samhain/Late Autumn, and it’s easy to understand why. It’s a major transition period on the Wheel of the Year and it’s filled with customs and traditions that many of us think of as pagan. We aren’t alone in that line of thinking either, a whole mess of people believe that things like carving pumpkins and playing dress-up are intimately connected with a “pagan Halloween.” The truth is something else entirely, as both of those customs arose in Christian Europe. That doesn’t stop ignorant Christians from protesting Halloween though, as they’ve become thoroughly convinced that the majority of Halloween tricks and treats come from our ancestors.

I always get a kick out of people who try to replace Halloween (a mostly Catholic holiday in origin) with “Harvest Festivals,” which were truly the first real pagan holidays. At this point trying to argue that “Halloween isn’t entirely pagan” just results in blank looks, Halloween and its customs have become examples of rustic paganism because of the ghosts they stir up inside of us. I honestly feel like there are a whole lot of non-Pagans out there who are jealous of how we relate to the world, and therefore attempt to demonize practices that come naturally to people regardless of gods or God.

I always get a kick out of people who try to replace Halloween (a mostly Catholic holiday in origin) with “Harvest Festivals,” which were truly the first real pagan holidays. At this point trying to argue that “Halloween isn’t entirely pagan” just results in blank looks, Halloween and its customs have become examples of rustic paganism because of the ghosts they stir up inside of us. I honestly feel like there are a whole lot of non-Pagans out there who are jealous of how we relate to the world, and therefore attempt to demonize practices that come naturally to people regardless of gods or God.

When my wife and I visit local craft fairs we are always struck by just how pagan they feel to us. There are vendors selling antique looking brooms, hand-dipped candles, and goblets that just scream “ritual chalice.” None of it is explicitly designed for Modern Pagans, but it all feels pagan because much of it seems to reflect a simpler era. Old fashioned doesn’t necessarily imply paganism, but items that fit into a seasonal motif often do. Cinnamon brooms conjure up images of fall and hand dipped organic candles just seem like the thing to use on Imbolc, and it’s easy to imagine both items in the cottage of a village witch. There’s nothing obviously pagan in either item, but they are the kinds of things we might associate with a pagan household of any era. For me it’s another example of rustic paganism.

When something moves you, when it touches your soul, its origins no longer truly matter. I think it’s important to know where we come from, but it’s sometimes even more important to know where we are now. The echoes of other eras draw us closer to nature, so we celebrate them no matter their origins. To get back to the original discussion I was having a few weeks ago, Morris Dancing isn’t an ancient pagan practice, but it’s a practice that feels pagan, and in a sense has become one, a rustic pagan one.

1. Historian Ronald Hutton offers a brief but thorough history of Morris Dancing in his book Stations of the Sun (published by Oxford University Press in 1996). That’s where my information on Morris not being pagan is coming from.

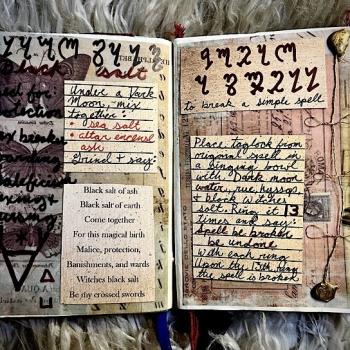

*I really wanted to have some photos of people engaging in ritual to use on Raise the Horns, hence the photo shoot. Some of the results showed up in this article.

**There are many different definitions of the word pagan. In my own writing when I refer to Modern Pagans I capitalize the word, for the other definitions of the word I use the lower-case. As you read, this may or may not make sense to you.