I received an email the other day asking me to share a Mabon Ritual invitation with a local list-serv. It was a beautifully written invitation as far as these things go and had the word Mabon front and center in rather large text. There was no slash (/) after the word, no further explanation or note about the Autumn Equinox, just a big Mabon.

I received an email the other day asking me to share a Mabon Ritual invitation with a local list-serv. It was a beautifully written invitation as far as these things go and had the word Mabon front and center in rather large text. There was no slash (/) after the word, no further explanation or note about the Autumn Equinox, just a big Mabon.

Most likely this doesn’t strike you as odd. “Mabon” contains just as much information as the word “Beltane” for instance. It suggests an approximate date and perhaps a ritual theme, at the very least it conjures up images of apples, pumpkins, and the grain harvest. I guess most of my surprise comes from my knowing of the continued resistance to the word “Mabon” in some quarters of Pagandom. It’s a resistance I’m so cognizant of that I often title my own equinox events as “Mabon/Autumnal Equinox.”

When it comes to those sabbats there are some very real lines one can draw in regards to their names. There are basically three categories of “Pagan names” for the sabbats. (I’m using “Pagan names” to suggest titles for the sabbats not used by the general public. Samhain is a Pagan name, Halloween is not, even if they are used by some of us interchangeably). There are five sabbats whose names can all be linked to genuine ancient pagan celebrations. Not only that, all five of those sabbats continued to be celebrated in some manner (or have its customs honored) after most pagans had converted to Christianity. Even many of the Christian names for these holidays are quite old, some stretching back over 1000 years.

The Five With Historical Names:

Samhain: Celtic pagan holiday, echoes of it can still be found in Halloween.

Yule: Germanic pagan holiday, many of its customs were made a part of the Christian Christmas.

Imbolc: Celtic Pagan holiday, led directly to the Catholic Bridget’s Day.

Beltane: Celtic Pagan holiday, parts of which can still be found in May Day celebrations.

Lughasadh: Celtic Pagan holiday, later became the Christian Lammas.

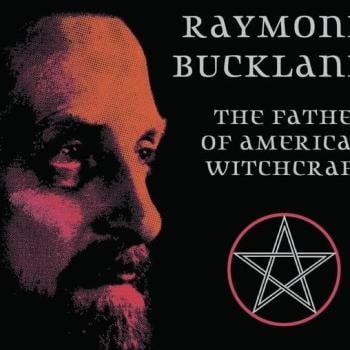

The “Pagan names” of the remaining three sabbats all have one thing in common: Aidan Kelly. It’s Kelly who came up with the names Ostara, Litha, and Mabon back in 1970. The titles were his attempt to find “Pagan names” for sabbats without traditional sounding monikers. I can understand the reasoning; moving from a holiday called Imbolc to the rather clinical sounding Spring Equinox lacks a certain romanticism. Two of Kelly’s names were completely inspired and have the same root source: they were adapted from the English historian Bede. (I don’t particularly like the word Litha myself, I still use Midsummer, but I understand the appeal.)

The Two With Common Origins (That Also Make Sense):

Ostara: Name of a Germanic fertility goddess found in Bede, also the Anglo-Saxon name for the month that contains the Christian holiday of Easter. It’s likely that customs and traditions associated with the Spring were absorbed into Easter.

Litha: Another Anglo-Saxon month found in Bede, also found in Tolkein. Summer solstice traditions were absorbed into the Christian St. John’s Day. Often also called Midsummer.

Ostara is a divinely inspired name choice. It fits the Spring Equinox so well that it feels like it’s always been there. That there’s no evidence for a Northern pagan celebration of the Spring Equinox is immaterial. The very word Ostara makes us feel as if the holiday in question has always been around. As Ronald Hutton writes:

“All the six other festivals in the Wiccan system have ancient equivalents, manifested both by specific mention in early texts and by a clustering of subsequent folk customs. The equinoxes lack both these attributes. The spring one has no recorded festival associations in northern Europe before the arrival of the Christian Easter, which, of course, can occur almost a month later.”

The only thing the name Mabon shares with Litha and Ostara is that it was coined by Kelly. It’s not Anglo-Saxon like his other creations, nor is it related to a month or Bede. Mabon is the name of a Welsh hero (or perhaps god) whose name literally translates as “Son of the Mother.” It’s theorized that in the character Mabon Kelly saw a parallel with the Greek Persephone’s descent into the Underworld*.

The Outlier:

Mabon: Name of a Welsh hero (or god) that translates as “Son of the Mother.” No linguistic link to any Christian or ancient pagan holiday. Bede mentions our modern September as a “holy month.” The celebration of Harvest Home was once common and traces back to at least the 1500’s.

What’s surprising about the choice of Mabon as a name for the sabbat was that there were plenty of alternatives. Bede had a name for September, Haligmonað, and wrote of it as a “holy month,” though he left no clear instructions as to how that holiness was celebrated. It would have been pretty easy to turn Haligmonað into Halig, much like Bede’s original Eostermonað became Ostara. (The more I say Halig out-loud the more I kind of like it. Happy Halig to you all!) It certainly would have been a pretty logical step and would have kept Ostara and Litha “in sync” with one another.

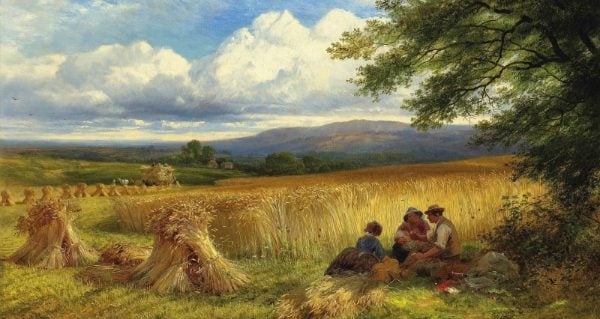

The English holiday Harvest Home was a very real holiday for centuries. There was no set date for Harvest Home but the things that were celebrated on the holiday are what most of us would expect in early Fall. There were games, ritual celebrations of the harvest, corn dollies, feasting, and parades. Many of these may or may not be “ancient pagan” in origin but they certainly all feel pagan, and are at the very least pagan in the sense that they revolve agricultural cycles. However the reluctance to use Harvest Home is understandable. Unlike Litha and Ostara it simply doesn’t sound ancient. I think some Modern Pagans deliberately avoid names like Midsummer for similar reasons.

Given that it has no real ties to the equinox I’m astounded at just how popular the word Mabon has become in Modern Pagan circles (especially in North America). If Mabon’s victory is not complete it’s almost nearly so. It’s in books, it’s online, and many of my friends have looked at me with blank expressions when I’ve used the term Harvest Home. At least Mabon rolls off the tongue and is easily pronounced.

Given that it has no real ties to the equinox I’m astounded at just how popular the word Mabon has become in Modern Pagan circles (especially in North America). If Mabon’s victory is not complete it’s almost nearly so. It’s in books, it’s online, and many of my friends have looked at me with blank expressions when I’ve used the term Harvest Home. At least Mabon rolls off the tongue and is easily pronounced.

The term Mabon has triumphed in a second way as well. I think people (and especially Modern Pagans) simply love celebrating the harvest and the Fall. In some parts of the Western World Samhain is nearly always an indoor ritual and its celebrations of the harvest are often downplayed to focus instead on death. Mabon gives us that moment to celebrate a triumphant Fall when it’s still generally warm and sunny, even in the early evening. Amongst so many of my friends there seems to be an extra level of excitement in the air during the Autumn. Mabon may not be the perfect word to capture that energy, but it has captured it none the less.

Happy Mabon! (Or Happy Halig! I really like that one.)

Note: I wasn’t serious about replacing Mabon with Halig (pronounced Hahl-ig) considering the point of this post was to share just how prevalent and ingrained “Mabon” has become in greater Pagandom. However, if enough people get on board . . . . stranger things have happened. I didn’t write this piece with the intent of getting a bunch of people to adopt Halig as a new name for the Fall Equinox.

* See the link above to Ronald Hutton’s Modern Pagan Festivals: A Study in the Nature of Tradition from the journal Folklore, issue 119.