Within British Traditional Wicca (called in Britain simply “Initiatory Wicca”), there exists a structure known as the degree system. One’s first degree is initiation, or becoming one of the Wicca. Second and third degree initiates are acknowledged to be more experienced initiates of progressively greater skill, talent, or “power.” But what does it all mean in practice? In order to answer this question, let’s discuss the parallels that the medieval guild structure has with the Wiccan degree system.

A guild was an association of artisans who controlled the practice of their craft in a particular town. A few guilds in France even gave rise to the earliest of the universities, where our modern academic degrees—bachelor’s, master’s, doctorate—retain this guild-like structure: apprentice, journeyman, master. For those not conversant with matters medieval, here is a brief description of the guild structure:

Apprentices lived with their master while being taught the craft; parents paid for the apprenticeship. An apprentice did not marry until apprenticeship was over, and in return the master guildsman taught well. At the conclusion of apprenticeship, the youth became a journeyman, who had fully learned his trade but was not yet a master. He now earned a wage and was expected to save enough money to start up his own business. For the journeyman to become a master, he had to submit a master work piece to a guild for judgment. If the work were deemed worthy, the journeyman would be admitted to the guild as a master. (1)

However, an extremely significant difference exists between the craft guild system and the Craft or Wiccan degree system. That difference is simple—there is no requirement for any initiate to seek elevation to a higher degree. In the trade guilds, apprentices are expected to complete training in trade skills and rise to journeyman status as an employable worker in that trade. Mastery is not a guaranteed status, for that requires a certain aptitude or talent beyond the skills, whereas apprentices become journeymen or “flunk out.” In contrast, in the Craft an initiate may continue at first degree without seeking to achieve a higher degree, as they choose. Initiates may, equally, choose to seek elevation as they grow in their Craft and in their life.

Let me state clearly, here, that one must seek out training, initiation, or elevation in British Traditional Wicca. One must ask, or one does not receive; the Wicca do not proselytize. At the same time, asking does not guarantee that any candidate will be accepted for training with a coven’s outer court, initiated into a coven, or elevated to a higher degree. Receiving a yes or no answer from one coven may not be the final answer—but no is a valid answer. Coven leaders make their decisions for the good of their Craft and their coven. Often, no means “not now” or “not with these elders” or “I don’t know why, but my Spidey-sense says not him, or not for us.”

My Journey: Seeking

My first encounters with one of my initiators came about entirely unbeknownst to me. Having stepped out of my solitary witchcraft practice by volunteering with a local pagan non-profit, I arranged to offer a multi-session class on making a robe for magical work using a medieval Anglo-Saxon garment structure—I’m a lifelong medievalist. A fellow volunteer (and, I later learned, second-degree witch running a maiden coven) brought the class to her High Priestess’s notice. Both were among my students and found it good, but I was entirely unaware at the time that I was being evaluated. Another student of that same class became my working partner when I was initiated. Thus does synchronicity run busily through the Craft.

The poem that follows came out of a dream-journey that occurred during my solitary studies in witchcraft, more than a year before I was offered the opportunity to study with my Wiccan teachers.

Her Summons

Hearing, feeling, knowing need,

Answer I, “Of course.”

Setting forth on path I walk

Further, further north.

Plays a tune I cannot sing,

Yet echoes in my throat,

Welling up to fill the lack

Encountered of a note.

Darling dark I knew of old,

Bright canvas of the sky;

Now through the murk demands of me

A leader’s simple cry.

I feel the tug and still I hold,

Uncertain of my way.

My answer’s mine and may not meet

The questions being played.

The call is strong and need is high,

Yet hesitate I more,

Reluctant to impose my voice:

An oracle…or whore?

—1994 CE

Apprentice

Historically, an apprentice was contractually bound for a set period of time (usually seven years) to serve a master at a trade or craft—weaving, metal-smithing, carpentry, stone-working, etc. The apprentice’s duties were often simple labor at the outset, cleaning the shop and learning the most basic activities by observation and instruction: the names and uses of the tools of the trade; the materials used and how they were acquired, stored, readied, and put to use; and the social interactions of the shop, between customer and master, or master and workers, which might include lesser masters, journeymen, and other apprentices.

The duties of an apprentice were to learn his trade in all its aspects, and to keep the secrets of that trade. The master committed in his turn to train the apprentice in the specific trade—the obverse side of the contractual coin. The master provided instruction at the level needed and opportunities to learn by doing. He also corrected the inevitable errors of a novice and remedied the difficulties encountered in novice projects. (2)

The First Degree

In British Traditional Wicca, one’s “apprenticeship” begins with initiation. At the time of Gerald Gardner’s initiation in 1939, witchcraft was illegal in Britain. As described by Gerald Gardner, it was only during his actual initiation that he even discovered that the coven initiating him were witches. “I was half-initiated before the word ‘Wica’ which they used hit me like a thunderbolt, and I knew where I was, and that the Old Religion still existed.” (3)

Gardner’s initiation was when he began to learn the Craft specifically. His long interest in matters magical and occult informed his witchy education, but it was not until he was a sworn “brother of the Art Magical” that any information was shared—be it written or oral or action. Like the apprentice of old, Gardner was oath-bound to keep the secrets of the Wicca.

Gardner’s initiation was when he began to learn the Craft specifically. His long interest in matters magical and occult informed his witchy education, but it was not until he was a sworn “brother of the Art Magical” that any information was shared—be it written or oral or action. Like the apprentice of old, Gardner was oath-bound to keep the secrets of the Wicca.

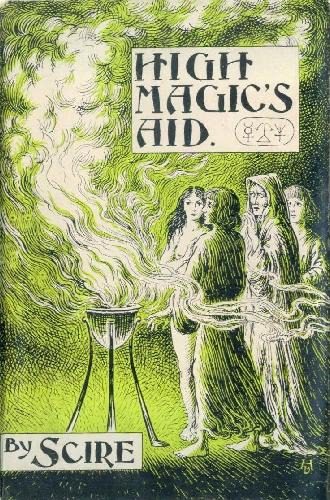

In Gardner’s published non-fiction, he states that he may not describe the magical techniques and words that the Wicca use in their rites; he is keeping his oath of secrecy. For this reason, when writing his 1949 novel High Magic’s Aid, he instead used material from the 19th century McGregor-Mathers English translation of The Key of Solomon (a Latin grimoire of ceremonial magic) to flesh out the scenes that depicted magical workings (spells). Our rites are transformative, productive of subtle change in those who undergo them. Any new initiate is exposed to words and actions and energies within the magical circle that are outside of prior experience. (4)

It is often said that one’s first degree is especially about getting to know the Goddess, a reality necessitated by the patriarchal roots of modern culture, one in which the very title Pope means “father.” Like the apprentice, a new initiate has duties which are, primarily, to learn: to know the Wiccan calendar, to call a quarter, to structure a ritual, to memorize an esbat ritual, to cast a circle, etc.

My Journey: Initiation

During my solitary studies as a witch, I celebrated the Wheel of the Year around, and culminated that year with a self-dedication rite among the redwoods on my birthday. Somewhen during those studies, leading up to that dedication, a dream-journey found me being named by Lady and Lord—who told me that when next I heard that name, I would know that They called.

Fast-forward a couple of years, to my initiation into Gardnerian Wicca. One of many items I had been instructed to bring for that occasion was my witch name. The humorous article known as Lady Pixie Moondrip’s Guide to Choosing a Pagan Name was at least two years current on AOL as well as the World Wide Web by that time, and I had no inclination to operate in such an irreverent fashion. I had determined that since I was already “out” as a witch by my mundane name, and had no guidance otherwise through divination or dreams, I was going to stick with the name Deborah.

Thus, when asked by what name I would be called, I opened my mouth to say, “Deborah”…and what fell from my lips was another name entirely. And as They had promised, I knew my name when I heard it, knew that They were present, and that I was where They wished me to be.

The solar-calendared rituals follow what is now called “the Wheel of the Year” in a neat progression of eight sabbats at the solstices and equinoxes alternating with the cross-quarters that begins at Hallowe’en. Hallowe’en, Candlemas, May Eve, Lammas, these are the fire festivals central to the Wicca. (5) One sabbat ritual at a specific season is a scant introduction to that sabbat’s energies as well as its traditional ritual.

The solar-calendared rituals follow what is now called “the Wheel of the Year” in a neat progression of eight sabbats at the solstices and equinoxes alternating with the cross-quarters that begins at Hallowe’en. Hallowe’en, Candlemas, May Eve, Lammas, these are the fire festivals central to the Wicca. (5) One sabbat ritual at a specific season is a scant introduction to that sabbat’s energies as well as its traditional ritual.

Think about it. You may remember one special Yuletide, but it is more likely that, for instance, you think of youthful summer camps or Mardi Gras events as a collective montage that is seasonal in nature and features a number of actions and feelings that mean that time of year to you. So it is with our sabbats. Doing them more than once takes more than one year.

For this reason, the lunar esbat rituals become familiar to the new initiate much more quickly. Celebrated once or twice monthly at full and new moons, frequent repetition aids both the memorization expected of initiates and aids them to perform the energetic steps that occur in creating, working, interacting with deities, and concluding any ritual circle. By the time initiates have completed a year working in coven, they have experienced at least twelve esbat rituals as well as the four fire festivals, and more likely all eight of the currently practiced sabbats. (6) They will have memorized the esbat ritual text and actions used in coven, and the annual progression of the sabbats have taught the basics of the Wiccan progression of seasons and energies. An experienced first-degree initiate can call a quarter, or all four, perform a simple traditional circle solo if required, work with an experienced partner to lead a pre-arranged esbat or sabbat within the coven, and aid in the general running of the coven. Energetically, the initiate will raise and ground energy as led by the coven leaders or elders.

If the initiate is working towards a hoped-for elevation to the second degree, the necessary first degree material has been completely hand-copied into the initiate’s own book of shadows. Likely the initiate has pursued individual own study interests in support of the coven or personal practice. Within a particular coven’s practice, the initiate may be assigned reading, writing, or practical exercises to complete as a part of training. Thus, sometime following that oft-quoted “year and a day,” a first-degree initiate may be elevated to the second degree. (7)

This is just part one! Click here for part two, and here for part three.

About Our Guest

About Our Guest

Deborah Snavely has been a Gardnerian initiate since 1995, and became an elder in the Craft in 2001. The following year she founded her first coven, a second followed in 2010. During the 1990’s she was editor of Pagan Muse & World Report, which won a Reader’s Choice Bronze Award from the Wiccan/Pagan Press Alliance in 1996. Deborah was an early online presence and hosted a weekly Pagan/Wiccan Discussion Group at AOL’s Religion and Ethics Forum. That forum was named “One of the 50 Best Places to Be Online”by PC Week Magazine in 1995.

Deborah has been studying divination since 1975, and has worked as a professional reader. Her favorite deck is the Robin Wood Tarot.

NOTES

1. http://www.a-london-tourist-guide.com/medieval-guilds.html

2. Apprenticeships often included fostering; apprentices were housed and fed and clothed by their contracted master, living as a part of his extended family. I do not discuss this aspect of the master-apprentice relationship here, except to note that it existed—its relevance to Wicca is that a coven leader’s role often seems quasi-parental.

3. The Meaning of Witchcraft, Gerald B. Gardner, 1959

4. Wicca is often called an experiential religion for this reason—it is not about believing, it’s about doing, experiencing, and dealing with the result.

5. Historically, the four cross-quarter sabbats or “fire festivals” of Candlemas, Beltane, Lammas, and Samhain or Hallowmas were the Wiccan large events; the solstices & equinoxes were celebrated at the closest full moon circle or esbat. A particularly successful Yule ritual in the late 1950s in Gardner’s coven led to the coven asking to celebrate the solar quarters as separate sabbats.

6. For simplicity’s sake, I write as though no one ever catches the flu or has an auto accident or a close relative die.

7. The phrase “a year and a day” describes one full year counted inclusively‚ a term used in mathematics but most often applied to the calendar. Example: one full week, counted inclusively, is 8 days Sunday through Sunday. The same effect arises in music, where an octave (meaning eight) higher is seven half-tones up from the original pitch.