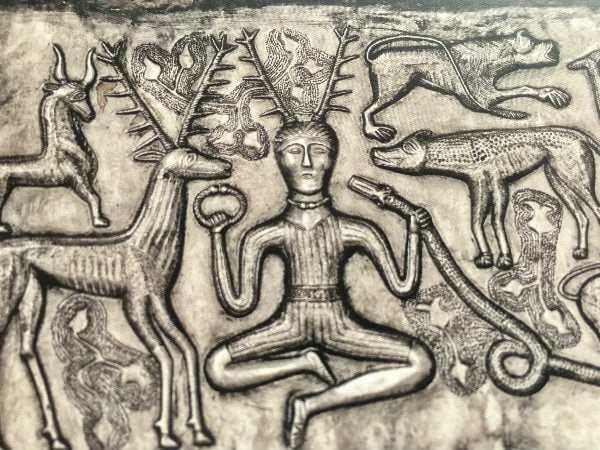

On September 7 2016 I visited the National Museum of Scotland in order to view The Celts exhibit. Like many Pagans I’m fascinated by ancient Celtic deities and culture. The whole exhibit was interesting but I was really only there to see one specific artifact: The Gundestrup Cauldron.

Generally the Gundestrup Cauldron resides at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, but has spent much of 2016 in the British Isles, at the British National Museum and the Museum of Scotland respectively. My trip to Edinburgh in September was planned around two things: whisky and seeing the Cauldron (and not in that order). To me it’s one of the most precious and important pieces of art in human history, and that’s because the Gundestrup Cauldron is home to the most striking and complete ancient image of the god we call Cernunnos.

The Gundestrup Cauldron would be remarkable even if it lacked Cernunnos. Found in a peat bog in Denmark, the bowl its self is a synthesis of several different cultures. Most likely manufactured near Thrace (near the border of modern Turkey and Greece), the Gundestrup Cauldron contains scenes that are strikingly Celtic, and others from the Middle East and as far afield as India. The animals depicted in various spots on the Cauldron come from all over Eurasia, and are not limited to Europe. It’s likely that the Cauldron was used by a Celtic tribe, but just why it’s so “worldly” is an open question.

When I saw the Cauldron it was placed directly in the middle of the Celts exhibit. While my wife and I were touring the exhibit it nearly called out to me. I could feel its presence, no doubt amplified by my decades long desire to see it with my own eyes. It’s far larger than most people realize, and the famous panels on it look like they were designed to be removed (they appear “clipped” on). The bottom part of the Cauldron was the “working bowl” portion and where the “magick” probably took place. Pictures of the Cauldron reveal the 3-D nature of the artwork, but don’t do it justice. I was amazed at just how strongly the images of animals and deities pop out of the Cauldron’s silver plates.

The plate depicting Cernunnos is on the inside of the Cauldron, and is remarkably different from the other deity images on it. Generally the Cauldron depicts deity-like figures as larger than life, Cernunnos is shown as smaller than most of them. But that doesn’t take away from the power and mystery he seems to wield on the Cauldron.

Cernunnos is undoubtedly one of the most popular gods in all of Modern Paganism. Romanticized versions of his image have become the de facto version of the “Horned God” archetype, and his devotees are legion. It’s worth pointing out that technically speaking, Cernunnos is not a horned god. There are antlers on the top of his head, and antlers are very different than horns. Antlers are shed annually while horns are for life. There’s also nothing linking Cernunnos to fertility either, and the occasional images of Cernunnos with an erect phallus are modern interpretations, not related in any way to how the god was seen in the Ancient World.

By ChrisO. From WikiMedia.

Writing about Cernunnos is challenging because we know so very little about him. We have pictures and statues of Cernunnos from antiquity, but what we don’t have are mythologies. Cernunnos is a god without a story. All that we know about his worship in the ancient world comes from the images we have of him. From those we can infer certain things, but even then, there’s nothing that can be known with absolute certainty.

There are some scholars who argue that Cernunnos is not even a god, they say that perhaps he was just a well known chieftain or warrior. There case is bolstered in some ways by his very lack of name. The word Cernunnos appears only once (and even then without the “C”) in antiquity, on a stone pillar found at the present day spot of the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris France. That pillar, known as the Pillar of the Boat Men, contains the very recognizable head of Cernunnos, and it’s similar to the image on the Gundestrup Cauldron, containing both antlers and torcs. Cernunnos shares the Pillar of the Boat Men with several Roman gods as well as Gaulish-Celtic ones, I think it’s great to see him standing so close to Jupiter and Vulcan. The pillar dates to about the first century CE.

There are other ancient artifacts with a name that was probably meant to be Cernunnos,. Two metal plaques found in Luxembourg bear the name Cerunincos, most likely in reference to either Cernunnos or a deity like him. A Gaulish inscription found in Southern France, and written in Greek, has also been found that uses the name Carnonos. After that the written record stops, and there’s no general consensus on what Cernunnos means in Gaulish.

To figure out who Cernunnos was to his ancient devotees we are left with using his depictions as a guidebook. Depictions of Cernunnos are remarkably consistent and generally contain a combination of the following things:

1. Antlers. Most statues and drawings of the god have antlers. Even the ones that no longer have them may have had them in the past. Several Cernunnos statues had spots for removable antlers, perhaps his antlers were changed depending on the season?

2. Torcs. Cernunnos is almost always depicted with a torc. Sometimes he’s holding one, and sometime’s he’s wearing one. Torcs were a symbol of wealth, power, and nobility in ancient Gaul. From this we can conclude that Cernunnos was associated with those things.

3. Sitting position. Cernunnos is the rare god who is generally depicted sitting. Even when in proximity to other standing deities he still sits. This is often linked to the lotus position of India, and it’s certainly possible. But a more likely explanation is that Cernunnos is sitting is a Gaulish hunting posture.

4. Snakes. Cernunnos often carries snakes in ancient art. Snakes are sometimes linked to prophecy, and in some Celtic myths snakes were said to guard hidden treasure.

5. Coins. Piles of gold coins are often shown in proximity to Cernunnos, and often times he seems to be pouring them onto the ground.

These five attributes are common enough that I think it lays to rest the idea that Cernunnos was a mortal person and not a deity. Though generally confined to Gaul, images of Cernunnos can also be found in the British Isles (though I should point out that they are exceedingly rare), meaning this deity was honored in several different locales.

The Gundestrup Cauldron features four of the most common Cernunnos motifs, and does so without any reservations. While some scholars call the image on the Cauldron “the antlered figure” I think it’s safe to just call it what it truly is, Cernunnos. On the Gundestrup Cauldron his sitting posture immediately catches the eye, and he both wears and holds a torc. In his right hand is a serpent, and he sits surrounded by animals. Who else could this be but Cernunnos?

From the images of Cernunnos we can infer a few things about he was seen and worshipped in the ancient world:

1. He was a god of hunting. This can be inferred by both the hunting posture and the game animals seen around Cernunnos on the Gundestrup Cauldron. His antlers also suggest a strong link to the natural world. While the Pagan world often tends to look down on personal gnosis, in my own experience he’s come to me as a good of the hunt, I’m not alone in this either.

2. He was a god of wealth. We don’t tend to think of “horned gods” as money gods, but Cernunnos clearly was. The torcs emphasize wealth, and the depictions of Cernunnos with coinage only confirm this interpretation. Snakes and their association with treasure are another indication of this.

2. He could have been associated with death in some way. Hunting involves death, but there are other links. Detachable horns on some statues suggest that Cernunnos was linked to what we now call the Wheel of the Year in some way. A de-antlered Cernunnos could have represented a fallen deity, or one that simply reflects the annual cycles of birth and death in nature. In a few instances he is shown surrounded by boats or near bodies, both of which were ways that provided entryway to the Celtic abode of the dead.

Cernunnos owes much of his modern popularity to Dr. Margaret Murray (1863-1963) a capable and renowned Egyptologist who is far better known today for her works dealing with Witchcraft in the early modern period. In her book The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921) she helped to popularize the theory that the victims of the witch-hunts in Europe were part of an organized witch-religion. Murray’s witch-religion was god-centered and when she wrote the sequel to Witch-Cult she focused exclusively on that figure. Murray’s The God of the Witches (1931) not only helped create today’s image of the Horned God, it also created a Cernunnos far grander than that of the historical record.

In God of the Witches she writes:

A few rock carvings in Scandinavia show that the horned god was known there also in the Bronze age. It was only when Rome started on her career of conquest that any written record was made of the gods of western Europe, and those records prove that a horned deity, whom the Romans called Cernunnos, was one of the greatest gods, perhaps even the supreme deity, of Gaul. (emphasis Mankey)

It’s hard to imagine the “supreme deity” of Gaul being such an unknown, but the power Murray ascribed to Cernunnos helped to make him one of the most popular horned and/or antlered gods in Modern Paganism.

Murray also associated him with other deities (though she was not the first to do so), associations that have continued into the present day. The most famous of those associations was with the English figure Herne, but Murray only used Herne as a starting point. In her cosmology echoes of Cernunnos can also be found in Christian saints and the monsters of folklore:

The great Gaulish god was called by the Romans Cernunnos, which in English parlance was Herne, or more colloquially “Old Hornie”. In Northern Europe the ancient Neck or Nick, meaning a spirit, had such hold on the affections of the people that the Church was forced to accept him, and he was canonized as St. Nicholas, who in Cornwall still retains his horns. Our Puck is the Welsh Boucca, which derives either directly from the Slavic Bog “God” or from the same root. The word Bog is a good example of the fall of the High God to a lower estate, for it becomes our own Bogey and the Scotch Bogle, both being diminutives of the original word connoting a small and therefore evil god.

For many devotees of the Horned God (myself included) Murray’s “Old Hornie” has become a true term of endearment for the Horned one.

While I’m of the opinion that Murray’s grandiose version of Cernunnos helped to popularize his worship in Modern Pagan circles, I’m also of the opinion that people honor him because they’ve heard his call. Who is to say that Murray’s pen wasn’t pushed in some way by a higher power? Certainly we are in need of an easily reachable Nature God today, and Cernunnos has certainly come to fit the bill. To many of us he is “the defender of nature” even if that wasn’t his original function in Gaul.

Though much about the historical Cernunnos is likely lost to history, his presence today is certainly not in doubt. He has become a vital component of the modern Horned God myth, and a deity important to Druids, Witches, and all sorts of other Pagans. I’ve felt his power alone at night in the woods, in circle with my coven, and while standing over the Gundestrup Cauldron.