It’s become quite fashionable to bash and criticize Wicca over the past ten years. Some of the criticisms leveled at Wiccan-Witchcraft are legitimate, and many of them have led people in the Wiccan community to change and adapt their practices and language. But one criticism I’ve been seeing with increasing frequency is that “Wicca is full of cultural appropriation.” (Confused about cultural appropriation, this article by Scarlet Magdalene is a great place to start.)

Defining just what Wicca is has always been difficult. Since its introduction to the world stage in the 1950’s it has been described as both a fertility religion and a nature religion. And while love and respect for the natural world are an important part of my practice, I tend to think of Wicca as a magickal religion, since everything I tend to do as a Wiccan-Witch is infused with magick.

The spiritual beliefs of Wiccans have always been nebulous. Some Wiccans are atheists, others are hardcore polytheists, while the vast majority of practitioners most likely reside in the mushy-swamp of soft polytheism-a belief in individual deities that are most likely part of a greater whole. Belief has never united Wiccans and never will, but there are two things shared by just about all Wiccans: the sabbats and ritual practices.

The Wiccan sabbats evolved out of the great fire festivals of the Irish-Celts, though how those sabbats are celebrated today has very little in common with how they were celebrated 2000 years ago. The sabbats also arose out of axial tilt, which gives us the change of the seasons and the solstices and equinoxes. I guess that someone might claim that the Irish-Celtic sabbats were appropriated, but that seems far fetched, especially since the remnants of those sabbats (Samhain/Halloween, Brigit’s Night/Imbolc, Lammas/Lughnassa, Beltane/May Day) have been a part of the English speaking world for over 1000 years.

Winter and Summer Solstice celebrations are even older, and have been celebrated across the world. Mabon and Ostara are essentially new holidays, drawing from pre-Christian Europe for inspiration, as we all as modern literary sources such as The White Goddess (Robert Graves) and The Golden Bough (Sir James Frazer).

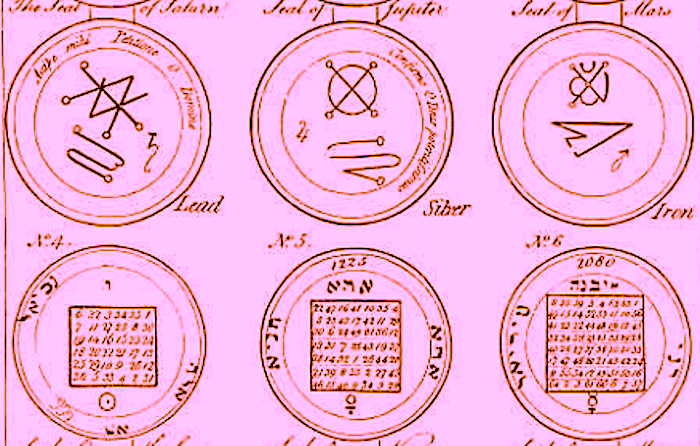

That leaves Wicca’s ritual as a source for possible cultural appropriation, a case which is even more tenuous. The standard Wiccan practices of casting a circle and calling in “the quarters” is an adaption of similar techniques found in European grimoires since at least the 14th Century, and before that in Muslim ones. That tradition of magick, The Western Magickal Tradition, has deep roots and could be found in Rome, Greece, Babylon, and Egypt in antiquity. The techniques themself were a blending of all sorts of things: pagan religions, folk magick, philosophy, and later Jewish and Christian elements. The ideas found in the Western Magickal Tradition were present in Africa, Europe, and Asia, and I’m not sure such philosophies can be appropriated.

For many Wiccans the centerpiece of ritual is “the working,” either a seasonal celebration or a magickal endeavour. The ideal seasonal rite speaks to local circumstances and is crafted by those engaging in it. Certain traditions have tried and true seasonal rituals; often adapted from previous magickal orders, or created several decades ago by the tradition’s architects.

I’m sure there have been some less than responsible (or cognizant) Wiccan practitioners who have attempted to shoehorn ideas far from Wicca’s origins into their rites, most especially material from Native American (First Nations) and African Diasporic religions and traditions. THIS IS PROBLEMATIC and often a legitimate claim of cultural appropriation. And while I don’t mean to make light of such practices, I do not generally see them in books or well-read online articles.

Many of the words used in Wiccan ritual do come from outside sources, but plagiarizing Aleister Crowley, the Golden Dawn, Charles Leland’s Aradia, and Margaret Murray is not the same as cultural appropriation. Often the words and meanings taken from those previous works were reinterpreted within Wicca to create something at the very least “newish.” Besides, religions have always borrowed (and stolen) from the various ideas that were floating around them, why would Wicca be any different?

WICCANS BEHAVING BADLY

Are there Wiccans actively engaging in cultural appropriation? Absolutely! But that’s not quite the same as saying that the practice itself is an example of cultural appropriation. Much of Wicca’s popularity comes directly from just how adaptable it is, it can readily absorb new ideas and ritual practices, and certainly some of the ideas and practices added by individuals are problematic.

I am not a gatekeeper for deity, and it’s not my place to tell someone a goddess, god, or other higher power is “off limits” to them. (And I would argue that to do such a thing, denies the agency of those higher power.) However, there are certainly deities that I don’t feel are appropriate in Wiccan spaces. Greek, Roman, Egyptian, Celtic, and Babylonian gods had all traveled far outside their places of origin by the year 0 CE. By that time many of them were also being worshipped in ways that were drastically different from that of their first followers.

In addition, many of those deities have been invoked in the rites and rituals of the Western Magickal Tradition for over 1000 years now. (Even the Christian grimoires sometimes name checked pagan deities.) I’m rather sure Pan is comfortable in my Wiccan circle because he’s been inhabiting such spaces for several hundred years. When he stopped being actively worshipped in Ancient Greece, he found a new home several centuries later in Renaissance Italy, and later 19th Century England.

But there are many deities who have never undertaken such journeys. The idea of invoking a Hopi Kachina into a Wiccan circle feels incredibly disrespectful to me. As does calling on one of the lwa of Haitian Vodou or a god of the Hindu pantheon(s). The context of a Wiccan circle is completely alien to such higher powers. There are ways to honor those powers outside of Wicca, and for those who feel the calling of such powers, they should engage with practitioners who can share how to honor them in a way that respects their origins.

In many ways Modern Wicca (which exists far beyond the borders of its initiatory origins) was born in the United States during the 1970’s and 80’s. Because of that, many things traditionally alien to Wicca were added to certain individual practices of it. Most noticeable are a whole host of “Native American” ideas, often spread by plastic shamans with no real connection to the spiritualities of the First Nations people. (Some of those ideas were legitimate, many of them were also completely made up, or completely ripped from the context they arose in.)

Do we probably all know Wiccans with dream catchers? I’m going to say yes, but those dream catchers are not a part of Wicca. Have most Wiccans been in a ritual with white sage? Again, the answer is probably yes, but the practice of using sage is not essential to Wicca, and was most certainly not used by Gerald Gardner or the other English pioneers of Wicca in the 1950’s and 60’s. Just about every tradition has individuals guilty of cultural appropriation, that doesn’t mean the entire practice is guilty of it.

In our more connected world today, more and more people are becoming cognizant of just what they should NOT be doing. Mistakes of the past are slowly (and yes it’s often far too slowly) being rectified in many communities. As the largest and most noticeable subset of Modern Paganism, the mistakes of many Wiccans are often front and center. That does not meant the entire faith as a whole is built on a foundation of cultural appropriation.

And no matter what our practice is, we should always take a few moments to be aware of its origins. If it’s something that doesn’t belong in what you do, don’t use it! Being respectful of the rites and traditions of others is something we can all do to make our world a little bit better.