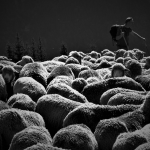

“Second German Baptist Church was located on the edge of Hell’s Kitchen, just a few blocks northwest of the Tenderloin district, where prostitution and gambling thrived. Street gangs and graft pervaded the culture of this community.2 Today Hell’s Kitchen is the trendy Midtown Manhattan home of actors and movie stars. But in Rauschenbusch’s day, it was the seedy underbelly of one of the world’s largest cities. Nothing in our country today truly approximates what life was like in Hell’s Kitchen in the late 1800s. If you’ve ever seen the Martin Scorsese film Gangs of New York, it was set in this same time period in the Five Points area of Manhattan, which was a similar, nearby neighborhood. It’s a violent and twisted film. Yet, if you can wade through the blood and gore, you’ll see that Scorsese did a masterful job of drawing out some of the heartbreaking social problems, inhumane working and living conditions, as well as the violence which was commonplace when Walter Rauschenbusch found himself leading that small German Baptist Church. Rauschenbusch believed the gospel must have something to say about these social problems.

Most German immigrants in the city lived in squalor, with multiple families crammed into each tenement building. Hell’s Kitchen was a crowded rectangle of apartment buildings and factories which stretched from Fifty-seventh to Thirty-fourth Street, and from Eighth Avenue west to the Hudson River. The Second German Baptist Churchwas located on West Forty-fifth Street near Tenth Avenue, smack in the middle of Hell’s Kitchen. In those days life along Ninth and Tenth Avenues was hard. Typically ten to fifteen people crowded into small, squalid three-room apartments. In addition to the rampant overcrowding, the low wages, crime, disease, unemployment, and hunger made life miserable and often short. Particularly heart-wrenching for Rauschenbusch was the impact on the children. It was reported that 68 percent of the deaths in that time and place were among children aged five and under.4 Rauschenbusch lived and worked among the people of Hell’s Kitchen. He experienced their struggles up close, living each day with the angst of desperate poverty.

What made this even more absurd was that all of this was happening while, just a few blocks up the street, New York’s high society was insulated from the suffering lower class. These were the days before labor unions, social security, unemployment benefits, and occupational safety regulations. Safe working conditions and fair wages were not the norm. There were few or no industrial codes and restrictions, nor were there child labor laws. Though some members of the affluent class made meager attempts at charity and relief, the harsh reality was the rich industrial barons and the middle class managers were getting filthy rich on the backs of the immigrant working class of Manhattan. Many of the family fortunes amassed during this period (Rockefeller, Carnegie, Vanderbilt, etc.), survive to this day, bearing witness to the jaded exploitation, abuse, and starvation of those who suffered in Hell’s Kitchen less than a mile from their opulent homes. Their exploitation of poor working class people became so ugly and transparent that they were given the pejorative nickname, “Robber Barons.””