When I listen to Rich Mullins’ music (and I still listen), he makes me want to go camping. It’s weird, I know, but it always seems like I could more easily imagine the world he imagined if I were off in the woods somewhere … and I really want to imagine the world that he imagined.

When I listen to Rich Mullins’ music (and I still listen), he makes me want to go camping. It’s weird, I know, but it always seems like I could more easily imagine the world he imagined if I were off in the woods somewhere … and I really want to imagine the world that he imagined.

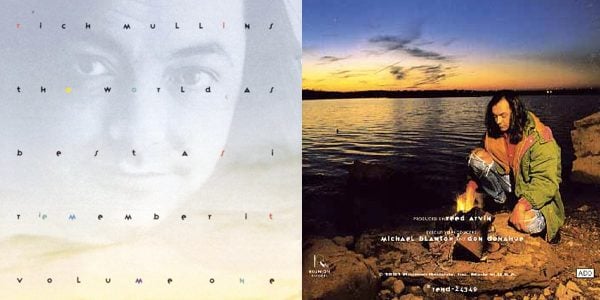

During his concerts Rich used to joke that his fans really think he lived on the edge of rivers lighting campfires (the cover of one of Rich’s popular records showed him doing just this). It was an illusion, and Rich loved nothing more than destroying our illusions.

But after all these years I still love Rich Mullins, and not because I’m hooked on an illusion. Back when I was playing with Satellite Soul we toured with Mitch McVicker (and Cobra Joe, and Brad Lahyer) for several years. I spent many a night smoking cigarettes under the stars and buying them beers to try to get them to tell me one more story about Rich. I think I have a pretty decent picture of the man. I still love Rich because he was clear-eyed about the world in which we lived and he could talk about it so artfully.

Rich embraced the darkness as well as any poet. He knew real pain. Rich did not see the world in black and white. He saw the world in deep, rich, velvety colors and textures–the very colors and textures he wrote into his songs. That’s the world I want to live in. That’s the world I want to imagine. That world is why Rich was so profound.

I was a rail-thin pimple-faced high school kid prone to spending long lonely hours in my room playing piano and guitar. I lived with an intense longing for I didn’t know what. Rich helped me interpret that longing, and my experience of the world. He helped me to root the longing in an ancient story. He gave my own story dignity and depth.

Rich insisted, argued, and wrote amazing songs in order to prove that the world is enchanted. “I do not meet God in a vacuum,” Rich wrote. “I meet Him in the world He has provided for me to meet Him in – in a world of events and of places, of history (time and space), in a world of lives of people and their records of their encounters. I meet God in this world – in the world of these things…”

Rich lived at the intersection of his own personal brokenness, the brokenness of the world, and the hope that we were not left here alone to struggle in the darkness without any help. Night after night Rich would play his songs for an audience for which I believe he felt equal parts compassion and disgust. I sometimes think it was Rich’s deep love of the physical world, of nature and the wonder of this place that we live that kept him from being terminally cynical.

Rich had an uncanny ability to describe the world as an enchanted place of wonder and awe and mystery. “I do not work myself into some ecstatic frenzy to meet God.” he said. “God does not speak to me through opium dreams or out of hypnotic trances. He meets me in history and takes me beyond it to Himself. Any “mysticism” that is authentic does not abrogate time and space – it infuses those elements with meaning. Time and space – that is the world.”

Rich was disgusted by people who lived without compassion. He railed against the politics of greed and the Christian right. He did this not to be like James Dean. He did this because Rich could see what we couldn’t see. “Look at us all” he said, “we are all of us lost and in all of our different ways of pretending, we all fool ourselves into the very same hell. Look at the cross – we are all of us loved and one God meets us all at the point of our common need and brings to all of us – all who will let Him – salvation.”

When Rich died it did strange things to me. I had embarked on my own journey as a professional musician and songwriter, doing my best to follow in his footsteps as I went, and all the sudden he was gone. Irving describes the sensation this way in Owen Meany:

“When someone you love dies, and you’re not expecting it, you don’t lose her all at once; you lose her in pieces over a long time—the way the mail stops coming, and her scent fades from the pillows and even from the clothes in her closet and drawers. Gradually, you accumulate the parts of her that are gone. Just when the day comes—when there’s a particular missing part that overwhelms you with the feeling that she’s gone, forever—there comes another day, and another specifically missing part.”

He died in 1997. The next year The Jesus Record released, then a few songs and remakes would trickle out here and there. Old concert footage would show up on the web. I didn’t lose him all at once. But now, more than ever, I can feel that he is gone.

I’m forty-eight years old now, seven years older than Rich was when he died. But if I live a hundred years, I’ll never be as wise as he was. And if I live to be a hundred I will never stop missing him. I will never stop repeating the final line from A Prayer For Owen Meany, that Rich once told me I should read: “O God—please give him back! I shall keep asking you.”