April Fools’ Day bothers me for several reasons. First, is there an apostrophe or no apostrophe? Is it acceptable to write “April Fools Day,” sans apostrophe? And if we are to go with an apostrophe, where do you put it? “April Fool’s Day” or “April Fools’ Day”? I’m pretty sure it is the latter, which means there is no way to write it without looking like a grammatical elitist, which is clearly not what this day is about. And how would you pronounce it? “April Fools-es Day”? Even the day’s title is incoherent.

Second, and this is my main objection. Pranks aren’t funny, they’re just mean. To play a prank on someone is to make them the butt of a joke they’re not in on. I don’t get how people can find any kind of pleasure out of causing another person’s discomfort, then laughing at them. It’s absurd. April Fools’ Day is just training in the lack of empathy, something at which are society seems to excel without the dedicated day. Seriously, why is it fun to cause a family member or coworker to look and feel silly and foolish? This was only funny when we were all completely immature, and even then…

This is why I could never enjoy Jackass, or the radio talk show cold-call pranks. I cannot enjoy watching someone intentionally make a victim of another person, unless I truly despise that person, which is a problem. Pranks and practical jokes trip my internal justice meter. They’re inherently unfair and usually kind of mean. So, fair warning: it might be April Fools/Fool’s/Fools’ Day today, but if I’m around someone who is playing a practical joke I will purposefully ruin the joke before it ever happens. And if the joke’s on me? Well then, to quote the great Rod Tidwell, “I don’t wanna be friends no more.”

Maybe there are exceptions to my “April Fools’ Day pranks are stupid” rule, like children attempting to pull an April Fools’ Day prank on their parents, or students with their teachers. This can be productive because it teaches kids one of the only effective ways to non-nonviolently resist or question authority. Pranks or satire become absolutely essential in many forms of opposition to oppressive regimes and authoritarian control.

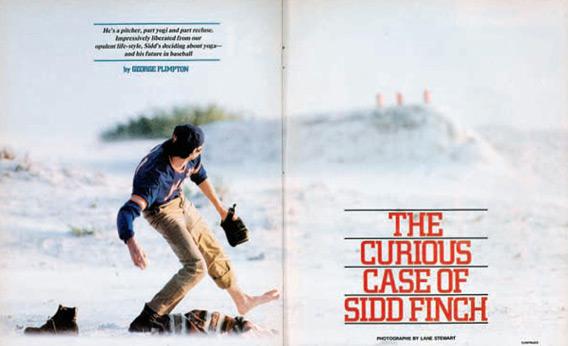

I also think that the elaborate news story hoaxes can be a rare April Fools’ Day exception. By that measure, in my opinion, the best April Fools’ Day prank of all times has to be the one engineered by George Plimpton in his 1985 Sports Illustrated article “The Curious Case of Sidd Finch.” Plimpton was asked to write an article on April Fools’ jokes in sports and couldn’t find anything noteworthy. So he decided to manufacture his own.

Plimpton’s feature article described a pitching prospect in the Mets organization. His name was Hayden Siddhartha Finch – “Sidd” for short. Sidd Finch was a 6-foot-4 phenom from Chicago, who grew up in an English orphanage, and was adopted by an archaeologist who later died in a mysterious Nepalese plan crash. Finch did a brief stint at Harvard but left school to study yoga in Tibet, where he became something of a zen master. His only possessions were a rug and a food bowl, and when he pitched he wore only one shoe – a ratty hiking boot. But he could throw a 168 mph fastball with pinpoint control. Despite his obvious talent and overwhelming advantage, Sidd Finch was currently deciding between professional baseball and the French horn.

Baseball was in turmoil about Sidd Finch, because he reportedly had not yet signed a contract. Finch was bizarre and aloof. He’d appear out of nowhere at the Mets’ training facility. Sometimes he’d pitch for 5 minutes, sometimes a half-hour. He was experiencing a moral-existential dilemma because baseball was based in greed, hatred, and deception – things Sidd had shunned. Nobody knew if he would actually sign a contract. Nobody knew if we would ever get to see him pitch.

I remember reading the article when it came in the mail. I couldn’t believe what I was reading, but I totally believed what I was reading. I wasn’t the only one. The Mets PR department was castigated for allowing Sports Illustrated to have an exclusive on Finch, instead of the New York media. Two general managers reportedly called the commissioner of baseball voicing concerns for hitters standing in the box against a pitcher with that kind of velocity. Reporters were dispatched to the Mets training camp to try and find the rookie pitcher. One radio host claimed to have seen Finch in action. And Mets fans? They went crazy.

The subtitle of the article read: “He’s a pitcher, part yogi and part recluse. Impressively liberated from our opulent life-style, Sidd’s deciding about yoga — and his future in baseball.” The first letters of each word spell out: “Happy April Fools Day – ah – fib,” (sans apostrophe, by the way).

It was genius.

Which brings me to the way I decide if a prank is good or bad, and whether or not to laugh. Good Pranks should never victimize gullible or weak people, but should expose the ways in which the strong and proud are ruining the world. Good pranks should be a an imaginative attempt to help us understand who we are as people, and as a society. A good prank is satire, we just don’t know it until we are “fooled.”

Plimpton’s article highlighted the American fascination with dominance and winning. Despite the obvious absurdity of Sidd Finch’s tale, we bought it. We believed it because we wanted it to be true. So we learned something about ourselves that day; something about our lust for winning, our quest for the silver bullet, and our appetite for world dominance.

So I will not wish you a happy April Fools/Fool’s/Fools’ Day, I will wish you a prank free April 1st.