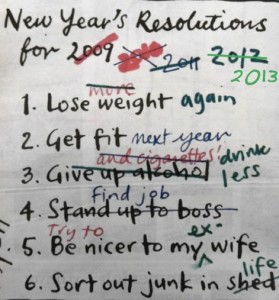

I don’t do New Year’s resolutions, and a few days ago I posted Emily Scott’s doubts about the idea of starting over, but there are times when I commit to a new project or effort. In early December, at my first checkup in too many years, I decided while talking with my plan’s health coach to set a goal to lose at least 20 pounds by Memorial Day. As part of that, I made some commitments about portion control and exercise. So far, I’ve adhered to the portion control plan, but the exercise? Not so much. I keep meaning to start. I keep finding reasons today isn’t a good day to take it on. Each time I feel entitled to do the wrong thing because… fill in the blank: I’ve had an aggravating day; I don’t feel well; I am too busy; I have plans later. This has been going on for weeks and I’m too embarrassed to admit it to my health coach, but does it mean I’m a bad person? Does it mean I’ve failed? No, it means I’m human.

People enjoy swearing off, and New Year’s is the biggest swearing-off ritual around. But all too often the best intentions come up against habit, craving, temptation or just fatigue, the abstainer slips, and then they feel like a failure. Sometimes the self-criticism blurs into self-hatred feeding a downward spiral that takes them to a worse place than if there had been no resolution in the first place.

The missing ingredient is love. All processes that involve self-restraint — whether once a year events like New Years and Lent, specific methods like Alcoholics Anonymous and Weight Watchers, or paradigms like original sin — all must be accompanied by love: both a sense of divine love for us, and a loving attitude towards ourselves. Without love, either we are simply “behaving” (or misbehaving), or we’re making some dry calculation of karmic reward and punishment.

A grounded place of love

St. Augustine (my patron saint) famously said, “Love and do what you will.” He means that if your actions are coming from a place of love — a grounded place of harmony with the universal connectedness of everything — then doing the right thing isn’t a struggle. He adds, “let the root of love be within; of this root can nothing spring but what is good.”

As easy as it can be to do the right thing when grounded in love, without that grounding a person usually can only behave for so long, in a state of what is sometimes called “white-knuckling it” — obedience without love — before the mind starts rationalizing giving up and temptations become too attractive. And even if you’re able to hold on for a long time, that doesn’t prove you don’t need love; only that you have a strong will. And that is no life. I’ve been there. I stayed sober for years once without having changed interiorly, without being grounded in God’s love. It was possible (until it wasn’t) but it was a constant struggle.

This love, this sense of groundedness and connection, is essential because we will fall short, sometimes in spectacular ways, usually in embarrassingly mundane ones. We are not saints. And actually, by that standard, neither are the saints. Read about their lives and you’ll find plenty of character defects at play. The point is: you aren’t God. So give yourself a break.

And that brings us back to St. Augustine with the terribly misunderstood concept of fallenness, of original sin. So often felt as a condemnation, recognizing your own imperfection can instead be a comfort. We all fall short. We all get caught up in temptations and turn away from God. This doesn’t mean everyone is evil, as some fire-and-brimstone types would have it. It means everyone is human. And being given permission to be human, to not live up to perfection, to make mistakes like every other human, is a pretty big load off the shoulders.

Jesus didn’t rebuke people for personal sins. He reserved his anger for hypocrites and those who disgraced the divine through their actions. But to the individual sinner, he said: Welcome, join me; change your ways but for right now, just have a seat. Jesus was radically welcoming and radically accepting. I’m not saying he didn’t find fault with behaviors, but he didn’t deem a person unacceptable because of their behavior. They were still welcome at his table. In fact, like the parable of the lost sheep, he paid more attention to those who needed to hear his message.

So if you want to make a New Year’s resolution, along with losing weight or quitting smoking, consider making a resolution to be understanding of others, and to have compassion for yourself. When you struggle while trying to live up to your best intentions, that’s not failure, that’s a reminder of the extent to which you are not running the show. Look at how hard it is for us even to follow through on some little resolution like exercising 20 minutes three times a week. And that’s OK. We’re only human. Just dust yourself off, ask forgiveness, and try to do better.

How is your New Year’s resolution going? Have you learned lessons from struggling with resolutions, this year or in the past, or with any other time when you’ve failed to meet your own best intentions. Share your experience here in comments. It will help others to know that none of us is perfect.