I’ve appreciated the thoughtful Matthew Lee Anderson ever since I came across his Mere Orthodoxy blog a couple years ago. When I learned he was writing a book called Earthen Vessels, focused on “why our bodies matter to our faith,” I looked forward to reading it. I remember how revolutionary it was for me when I came to understand (through Alexander Schmemann’s For the Life of the World) the implications of the Incarnation of Christ and the bodily resurrection. There is no bright line between our bodies and “who we are.” We are essentially, irreducibly embodied creatures, and this implies the original created goodness of the body, its entanglement in the sins of the spirit, and the futility of any philosophy or religion that seeks to disembody the self or to transcend the body in the spirit.

Anderson devotes a chapter to the increased frequency of tattoos amongst evangelical youth and what this tells us about the evangelical subculture and its relationship to the culture at large. Not so long ago, tattoos were, instead of chosen, imposed as markers of ownership — belonging to a gang, or a slavemaster, or a Nazi concentration camp. Also recently, tattoos were markers of social defiance and deviance, of marginalized people groups and underclass laborers. The tattooed were prison inmates, or bikers, or sailors, or sexual revolutionaries. As Anderson notes, however, tattoos have been “mainstreamed” both within broader American culture and more recently within evangelical Christian culture. Tattoos became less accidental (a girlfriend’s name on a drunken night) and more deliberate and expressive (a line from a poem, or an icon), less crude and more artistic, less provincial and more global (consider the frequency of Chinese characters, e.g.). Anderson cites an eye-opening statistic: Nearly 40 percent of young adults aged 18-28 have tattoos now, which is more than four times the number in the Baby Boom generation.

Anderson suggests that young American evangelicals are attempting to define themselves and thus establish a kind of fixed point of identity amidst the flux and instability of a deteriorating world. “The decay of the family, the emptiness of our church experiences, our geographical transience, the inability to find employment–these are the sorts of pressures that have left many young people with a lingering sense of emptiness and instability.” The practice of tattooing “treats the body…as an object for our self-construction,” and functions as an assertion of individuality. The tattoo is a constitution and a declaration of independence all at once.

Of course, Anderson appreciates the irony. Young people use tattoos to declare their individuality — because that’s what everyone else is doing. “While tattoos mark a desire for significance within a destabilized world, they are a live option for most young people precisely because we have not escaped the clutches of the consumerism and the individualism that are so often criticized” (112-113).

All of which is true enough. Anderson is a gifted anthropologist for homo evangelicus and homo americanus both. I just want to offer a few other thoughts:

(1) Tattoos as the search for permanence. As with any complex human behavior, the field of potential motivations here is vast. Since tattoos stand for permanence, Anderson is right that those who obtain tattoos are often — often — looking to assert something permanent and enduring about themselves. Here, they’re saying, is my essence; this is who I am and what matters to me fundamentally, and this will not change. Kierkegaard speaks of a kind of dizziness that one feels when one perceives one’s own nothingness. Looking down, we see that we are, at least apart from God, one layer of construction atop another, all the way down. We perceive our own freedom, perceive that we are a project of our own freedom, and the dizziness that follows when we recognize that we stand upon nothing but our own capricious self-assertion is enough to make us want to latch onto something concrete.

(1) Tattoos as the search for permanence. As with any complex human behavior, the field of potential motivations here is vast. Since tattoos stand for permanence, Anderson is right that those who obtain tattoos are often — often — looking to assert something permanent and enduring about themselves. Here, they’re saying, is my essence; this is who I am and what matters to me fundamentally, and this will not change. Kierkegaard speaks of a kind of dizziness that one feels when one perceives one’s own nothingness. Looking down, we see that we are, at least apart from God, one layer of construction atop another, all the way down. We perceive our own freedom, perceive that we are a project of our own freedom, and the dizziness that follows when we recognize that we stand upon nothing but our own capricious self-assertion is enough to make us want to latch onto something concrete.

(2) Tattoos as the Art of Self-Destruction. So with tattoos, perhaps we’re making ourselves our own construction projects. But tattoos can also express deconstruction, or even destruction, of the self. Let’s not forget that the person who gets a tattoo is

(2) Tattoos as the Art of Self-Destruction. So with tattoos, perhaps we’re making ourselves our own construction projects. But tattoos can also express deconstruction, or even destruction, of the self. Let’s not forget that the person who gets a tattoo is

intentionally inflicting pain and suffering upon himself. Tattoos can be rites of passage and tests of courage and endurance, and an effort to externalize suffering in the form of self-mutilation. In some cases, at least, tattooing can be similar to “cutting,” where a young person (typically) who loathes himself or wishes to punish himself indulges in repeated cutting. In this sense, tattoos can be an outward expression of inward self-hatred. Note the way he presents himself: not straight on, but askew, head slightly lowered, without a smile, with a long gaze that speaks of hardship and solitude. The symbols upon his face may have political significance, but they have psycho-spiritual meanings as well.

The man pictured on the right has done violence upon his body, both physical violence and a kind of visual, artistic violence. This is why, I think, tattoos amongst the “hard core” are often accompanied by other “bod mods” (or body modifications), which are really self-mutilations. Consider this person, who has made himself into an image of death and coordinated his tattoos with a nose ring and twin spikes emerging from the bridge of the nose. This is an especially literal example of externalizing the internal. The skull is presented upon the surface. This is not a striving for permanence so much as a brutal reminder of impermanence and decay. He has turned himself into a corpse.

The man pictured on the right has done violence upon his body, both physical violence and a kind of visual, artistic violence. This is why, I think, tattoos amongst the “hard core” are often accompanied by other “bod mods” (or body modifications), which are really self-mutilations. Consider this person, who has made himself into an image of death and coordinated his tattoos with a nose ring and twin spikes emerging from the bridge of the nose. This is an especially literal example of externalizing the internal. The skull is presented upon the surface. This is not a striving for permanence so much as a brutal reminder of impermanence and decay. He has turned himself into a corpse.

These examples go far beyond the tattooing we typically see in evangelical circles, but they may show in extremis what tattoos can communicate. Tattoos can be acts of self-construction, but they can also be acts of self-destruction. When our children express an interest in tattoos, especially if they go beyond a cross or a rose upon the shoulder, then parents might be wise to consider whether their children have been taught to love themselves and cherish their bodies, or whether their tattoos might be modern forms of self-flagellation.

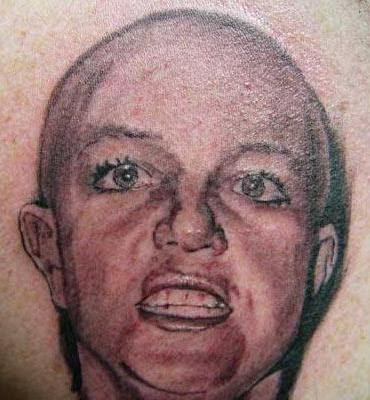

3. Tattoos that Celebrate Randomness. One trend I noticed when looking at tattoos online is that some celebrate the very opposite of transcendence and permanence: they celebrate fleeting moments in superficial celebrity culture. The moment when Britney Spears, her head shaved, raged against the paparazzi, or Maddox Jolie-Pitt, or Will Ferrell in “Elf”. These seem like the last images you would want to impress upon your body permanently — but that’s the point. This is a defiance of the passage of time, a celebration of randomness, weirdness, and the fleeting nature of pop culture.

3. Tattoos that Celebrate Randomness. One trend I noticed when looking at tattoos online is that some celebrate the very opposite of transcendence and permanence: they celebrate fleeting moments in superficial celebrity culture. The moment when Britney Spears, her head shaved, raged against the paparazzi, or Maddox Jolie-Pitt, or Will Ferrell in “Elf”. These seem like the last images you would want to impress upon your body permanently — but that’s the point. This is a defiance of the passage of time, a celebration of randomness, weirdness, and the fleeting nature of pop culture.

Tattoos are simultaneously deep and superficial. They’re deep in the sense that they’re lasting, even permanent. They’re superficial in the sense that they’re “only skin deep.” Perhaps tattoos like this communicate a fascination with surfaces. I am my surface, tattoos like this say. Life is nothing more than a random series of disconnected moments, and we have no choice but to revel in the absurdity and contingency of it all.

4. The Flesh Made Word. More common in general is the practice of tattooing Chinese characters, and more common in Christian circles is the practice of tattooing Bible verses or biblical or theological phrases. This is especially interesting in the light of the theology of the LOGOS and the incarnation. In the incarnation, the LOGOS, the eternal Word, became flesh. The LOGOS transcended the world and its changefulness, representing the eternal truth and the power by which all things were called into Creation. But when a Christian tattoos a Bible verse or a faith-phrase upon her body, she makes her body into a text. She reverses the incarnation of Christ; in her de-incarnation she is making the body, what is prone to messiness and effluvia and decay, into a true and eternal Word. They are turning themselves into the Bible, or a part thereof.

There’s something laudable in this: stating that these truths are the ultimate and unchanging truths of who I am. Yet I also wonder if they represent a running away from our carnality, a running away from the things that Christ affirmed in the incarnation. I wonder too whether tattoos like these — and all tattoos — might sometimes work like frosting upon a store window — presenting a surface that seeks not to externalize but to conceal what lies within. Does the person who stamps “God’s Son” upon his skin really believe it?