This piece is written as a companion to episode 8 of The Pop Culture Coram Deo Podcast and, like that episode (which you can play below, contains numerous spoilers. Subscribe to the show on iTunes, Stitcher, acast, Player.FM or stream at the link above.

Read on at your own discretion.

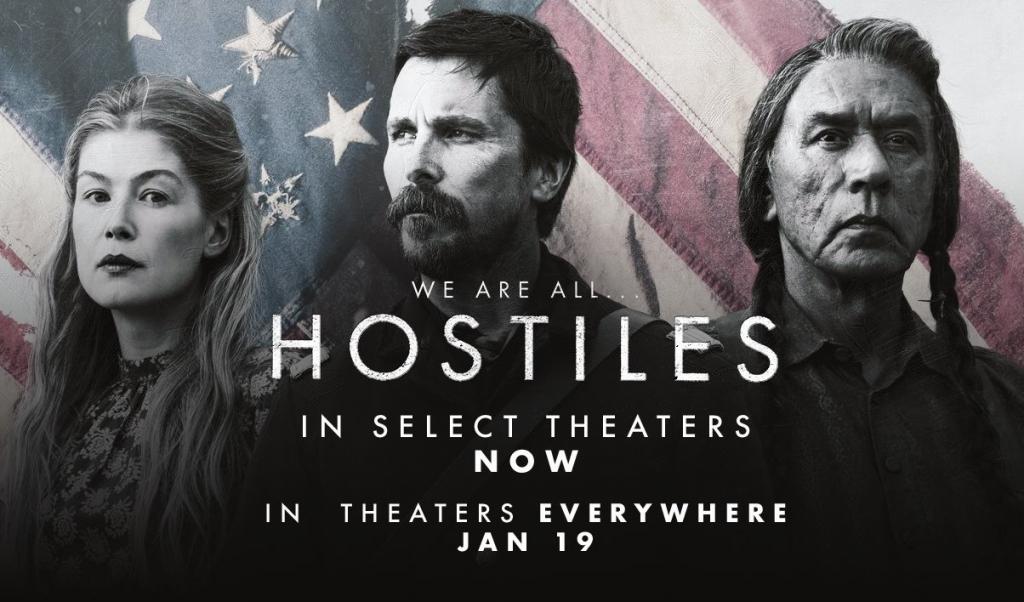

Hostiles will be released on Amazon Video and iTunes on April 10th, 2018 and home video April 24th.

– – – – – – –

My enemies are men like me.

So sang Derek Webb in 2005 and, while he did so speaking about the evils of war, the lyric missed its calling in a theme song to Scott Cooper’s Hostiles.

Hostiles is a film of violence – violence by the metric ton, heartrending, bloody, constant violence. More specifically, Hostiles is a film about the evils men do to one another in pursuit of financial resources, power, or whatever equally meaningless goal their heart’s affections has fallen on. All of this is evident from the first sequence – perhaps the most heart-wrenching and shocking of 2017.

Beauty as Backdrop

The film shows its audience just how monstrous violence really is by framing it against a beautiful background – in the opening scene you see the beauty of the household established by the ill-fated settler family of Rosamund Pike’s Mrs. Quaid most intimately. More broadly, creation itself (as opposed to the creatures that inhabit it) gives a beautiful literal landscape for the drama of Hostiles to play out against. In this way Cooper faithfully honors the Western genre’s tradition of revealing the natural world’s loveliness. But idyllic family life and the natural world are not the only aspect of beauty in Hostiles. Truth and goodness present themselves for appreciation as well: This film shows us human goodness in acts of mercy toward one’s enemies and the richness of both family and friendship. Male/female relationships are treated with dignity by the honorable characters in this film and dishonor by the wicked characters, both of which evidence the correct moral compass. This film also tells us that evil exists, both within and without, and should be opposed everywhere it raises its head.

Fully Fallen

The praise of the true, good, and beautiful doesn’t mean that the world of Hostiles is paradise. In fact, the world of the film is incredibly fallen. Men wound and kill their fellow men, the demons of war consume otherwise good men, selfishness leads to the loss of innocent life, and the corrupting effects of both war and politics sear the conscience of those who participate in them.

Our hero, Christian Bale’s Captain Blocker, is a man grown as hard, harsh, and unforgiving as the landscape of the American West in which he hunts Native Americans as an agent of the United States Government. Blocker appears to the audience the epitome of the D.H. Lawrence quote that Cooper chose to precede the opening scene of this film:

“The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer. It has never yet melted.”

In large part this hardening has happened in response to the atrocities committed by Wes Studi’s Chief Yellow Hawk. One of the most important scenes for understanding Blocker’s transformation over the course of the movie is found early in the film, in Blocker’s commander’s office, where Blocker recounts the names of friends killed by Yellow Hawk. In the face of Blocker’s recounting a smarmy newspaper man from out East begins to laugh only to find him cut off by the bristling rage of Blocker who warns him against any further laughter.

A Good Movie About Bad Things

Nonetheless I believe Hostiles is the kind of film Christians (at least those who can stomach the violence) will want to see. Fundamentally, Hostiles is a story about growth through mutual suffering, a growth that takes Blocker, Yellow Hawk, and Mrs. Pike from a legitimate alienation into an equally legitimate reconciliation. And while that is the best part of Hostiles in terms of storytelling there is plenty additional good.

Blocker’s band of soldiers, while initially very willing to allow Yellow Hawk to provoke a fight that would justify ending the chief’s life, are nonetheless men of honor. In testimony to the perseverance of the imago dei Blocker is able to maintain some vestiges of his humanity as he carries out, very effectively, his work of hunting down Native Americans for the United States Army. This allows him (and his men) to respond to Mrs. Quaid with deep, patient, and upright compassion when their party crosses her path. So too do the Native Americans in this film choose compassion toward a white woman who shrieks in anger and pain when she first lays eyes on them. Both streams of care eventually help Mrs. Quaid find some measure of healing and bring her to integrate herself with both the soldiers and the Native Americans, serving in some ways as a bridge that draws both parties together as well.

The Mechanism and Fruit of Reconciliation

The deeply realistic, although fictitious, Hostiles tells us something very true about reconciliation in the real world. Blocker and Yellow Hawk’s family (along with Mrs. Quaid) are brought together not in the end through becoming Conqueror and conquered but by the experience of suffering together. On the journey to return Yellow Hawk to his ancestral lands carried out in obedience by Blocker the band of companions encounters emotional devastation (in the discovery of Mrs. Pike), danger (from the threat of a Native American band rightly described as savages), betrayal (from within the United States Army), and predation (from roving fur traders). This experience of suffering together moves the company of travelers from, well, hostiles to co-belligerents then allies and, at the end, a very real kind of family.

In this way the journey of Blocker and Yellow Hawk, not so much over unforgiving terrain as over the terrain of their own unforgiveness toward each other, looks more than a little like the church. The heat of suffering breaks through the protective hardness of their heart so that both men are able to learn, legitimately even if not fully, the truth of 1 Corinthians 12:26. Blocker is so transformed that he identifies more fully with Yellow Hawk in death than he does with the living white people who would callously violate the dignity of Yellow Hawk’s family in their mourning. Even more richly, by the end of Hostiles (without giving too much away) we have a new family created, composed from men and women and children from every walk of life (and every genus of suffering) that echoes the work of Christ creating the new humanity called the church through His Son. In the ultimate model of the church it is the sufferings of Christ that bring formerly alienated men together. With that said, it is deeply Christian to see the experience of suffering as a unifying experience in a secondary sense.

A Comedy in the End

As a result (and in a kind of twist ending) Hostiles turns out to be a comedy in the classical sense. A community is revealed and something much like (or leading to?) a wedding feast caps the narrative. We begin the movie seeing Captain Blocker refuse to provide safe passage for Yellow Hawk because Yellow Hawk had killed so many of Blocker’s friends. By the end Blocker wishes Yellow Hawk a good death, much like a friend would. Cooper proves Lawrence incorrect, at least in narrative form – Blocker’s hardened, killer, quintessential American soul has melted – not in response to a great threat but through great threats, shared with other men, with the net result being the sight of shared humanity in his former enemies.