WARNING: Mild spoilers for Game of Thrones, The Good Place, The Lord of the Rings, and Lost.

Game of Thrones on HBO is now officially over, and as a long-time watcher of people watching Game of Thrones on HBO, it was prime viewing to see the shouts of disappointment over the series finale.

I’m far from the first to draw connections between fans of Lost crying out their disappointment over the conclusion to a high-concept TV show, but I’d like to take a moment to examine what went wrong in the storytelling.

A Game of Surprises

Years ago, I picked up the first book of Game of Thrones, a highly recommended novel by my local bookseller, and comfortingly thick – which promised either some excellent or overblown worldbuilding. I was thrilled to find myself drawn into the world of Westeros and – as people would do as soon as the first season aired on HBO – my mind was absolutely blown when Ned Stark was suddenly executed in book one.

After all: I knew how stories went. Ned Stark was our protagonist, surely? That must save him from any real peril. And this was high fantasy. Good vs. bad. And the Lannisters were very, very bad. I mean: in the second scene they committed incest and attempted child murder!

The death of Ned Stark seemed to symbolize that this wasn’t your father’s high fantasy. This was going to be a brutal and unjust world. So, when I finally got to the Red Wedding a few books later, while I was horrified, I wasn’t entirely surprised.

I did, however, search out author interviews with George R. R. Martin to see what his worldview was. Because by this point, I’d suffered through a lot with the characters, and I wasn’t sure I could handle more horror in the plot, unless the author was going somewhere ultimately redemptive with everything.

Unfortunately, what I found was that Martin subscribed fundamentally to a nihilistic worldview, and that while he was definitely interested in subverting the usual heroics of high fantasy, forged by J. R. R. Tolkien, he did not believe in either redemption or meaning in life.

Needless to say, I stopped reading his books.

And when HBO picked up the series, it was my previous brush with Martin (as well as the HBO treatment of women) that kept me from watching.

But, it was no surprise to me when the audience cried out in frustration at the conclusion. Because, as much as the HBO creators strayed from Martin’s (unfinished) script, they had been set a foundation of nihilism – and worse – they had given into the fundamental plot flaw:

Surprise vs. Story

Many storytellers are given the advice: “Surprise your audience.”

This is good advice, so far as it goes. Certainly, you don’t want to bore your audience, or have them so far in advance of your plot that they can name every twist and turn.

(In fact, I stopped reading one fantasy author when I realized what her formula was half-way one of her later novels, guessed the conclusion, flipped to the last chapter, realized I’d gotten everything right…and promptly threw the book against the wall and never bought another piece of work by her again.)

However, there’s the temptation to think that “surprise” is the sole element of plot – and if Game of Thrones and Lost have taught us anything, a story built on nothing but “surprises” will almost inevitably disappoint.

Why? Because surprises only work if they’re earned.

Just like writing mystery novels, surprises work if they’re intrinsic to the philosophy of the story that you’re telling.

Lord of the Ringers & The Good Plot

In Lord of the Rings, we’re told from the beginning that the power of the ring corrupts the bearer. We see Boromir and Gollum fall to the ring. We see that Gandalf is afraid to take it. So while it’s a surprise that Frodo cannot bring himself to part with the ring when they finally get to Mount Doom, and a further surprise that Gollum’s corrupt desire for the ring causes him to bite off Frodo’s finger for possession of it – it’s an earned surprise. It’s an inevitable surprise.

This is similar to the twists and turns of The Good Place, particularly Season 1.

(Which, if you haven’t seen it – STOP READING NOW AND GO WATCH. Seriously. One must witness that remarkable show entirely unspoiled.)

By the end of the first episode, we’re told the premise: our protagonist, Eleanor, was probably put in the Good Place by mistake. By the end of episode 3, we get our first game changer: Eleanor isn’t the only person who shouldn’t be in the Good Place. As the season goes on, every game changer is an inevitable surprise: Eleanor, searching for her place in the world, suggests early on that she probably should be in a Medium Place. So of course when she’s nearly sent to the Bad Place, she escaped to the Medium Place. Eleanor shouldn’t have been in the Good Place, so it’s an inevitable surprise when “Good Eleanor” shows up. We know that Eleanor is an unreliable narrator and not worthy of the Good Place, and her plight distracts from the various things that feel “off” about the Good Place – such as the idea of soul mates, or Tahani’s pride, or frozen yogurt instead of ice cream – so that the final, final twist of Season 1 – the seeming surprise, was actually seeded all along, and in keeping with the philosophic questions brought up in the very first episode.

What makes The Good Place even more satisfying, is that even knowing the plot twists, the truth of what the show is exploring is so woven into the fabric of every episode, that the entire show is rewatchable time and time again. In fact, knowing what the show is exploring at its heart only deepens the audience appreciation, even as they know all the surprises coming up.

Plot is not surprise. Plot is the unveiling of truth.

How Lost Got Lost

So Lord of the Rings and The Good Place are prime examples of how to use inevitable surprise by seeding philosophic truth throughout.

But let’s take a look at how Lost which built its “plots” not on ideas, but on pulling the rug out from under us.

Fairly early into Lost, the internet was buzzing with the theory that the mysterious island our castaways were on was really Purgatory: that everyone had died in the crash, and that they had to work out their suffering through each other.

Thing was: this was exactly what the show intended to do. But, rather than giving us the truth earlier – the way The Good Place does – they decided to throw “surprise” after “surprise” at us, until finally concluding back where they began.

What would have been more satisfying would have been if the creators of Lost had committed to its own premise and instead of thinking they had to surprise us to keep us intrigued, instead doubled down into the human existence and how our lives intersect and what that means.

Humanity – true humanity – is surprising in itself. The truth is always a revelation.

Game of Don’ts

Two of the biggest cries of outrage over the finale of Game of Thrones was the heel-turn of Daenerys from victim to queen to savior to megalomaniac. In this case, the general consensus is that the show merely needed more episodes to tease out this change. But that the actress had done her best with a single look at the camera…rather than the full story arc that she required.

In fact, part of the problem was that the HBO storytellers decided to kill the Night King – the main, looming antagonist of the series – a few episodes before the conclusion of the show. Without the overthrow of the series antagonist saved for the climactic action, a new antagonist had to be created and quickly.

Related, the other outrage was naming Bran as the High King of Westeros. The feeling most people received being the sense that the HBO storytellers were looking for a “surprise” candidate for the (now defunct) Iron Throne, and so chose Bran as the least likely to be guessed…rather than the most satisfying.

All of these frustrations arise, however, from the fact that neither George R. R. Martin nor the HBO interpreters of his work had a clear idea of what story they were telling. Was it about how power corrupts? In that case, focus on Daenerys’ fall from grace. Was it about the futility of power? In that case, let the dragon melt the throne and everyone disband. Was it about the need for balance? Then build up Bran as a viable middle point.

But, in truth, the creators of Game of Thrones simply wanted to “surprise.” Not to tell a story. Hence there could be no inevitable surprise, because there was no underlying truth they were constantly exploring to begin with.

A World of Pure Imagination

My heart goes out to everyone who watched either Game of Thrones, Lost, or any show that started so promising and then devolved into painful “plot twists.” (I’m looking at you Alias and How I Met Your Mother.)

But here’s a game I’d like to throw to you. If you were to fix your favorite show: what would be the theme that you’d explore, and how would you have ended it?

As for me? I’ve waiting for someone to put dragons in purgatory. That would be fun, right?

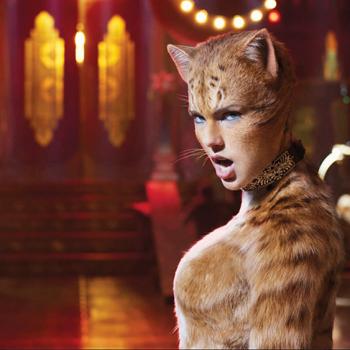

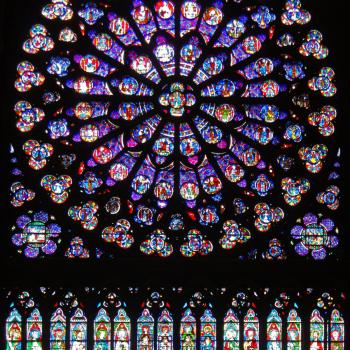

Photo courtesy of HBO and ABC.

Become my patron on Patreon!