Marzena Sowa’s memoirs of growing up during the fall of communism in Poland demand to be told in the graphic novel genre. Her experiences, emotions, and memories transcend words. While much of Sowa’s childhood provides opportunities for readers to connect with her, there is so much more that takes us to a place and time that many of us don’t…and hopefully will never…know. In her new graphic novel, Marzi, Sowa does a magical job of weaving the two together–the familiar and the unfamiliar–to create an uplifting narrative that is a delight to read…and to look at.

Marzi’s life is full of youthful wonder. That she grows up in communist Poland only adds to it. She attempts to make sense of ration cards, long lines, limited goods (even toilet paper), and her own parents’ financial troubles. Though times are hard for Marzi and her family, they always seem to have just enough to get by. They also benefit from an extended family network, the members of which take good care of each other. Like other children her age, Marzi attends school and must navigate both educational and friendship highs and lows. During her school breaks, Marzi and her parents take frequent “vacations” to family members’ farms where they help work in the fields. Along with trying to make sense of the adult world of her parents (as all children attempt to do), Marzi is faced with a nearly incomprehensible political system that plagues her life…somewhat inadvertently. She knows her parents suffer but not why. Even though she doesn’t fully understand political events that happen around her, her description of them and changing socio-political times are quite simply beautiful. It is a testament to Sowa that she doesn’t let her contemporary reflections on and understandings of these events “pollute” her childhood recollections.

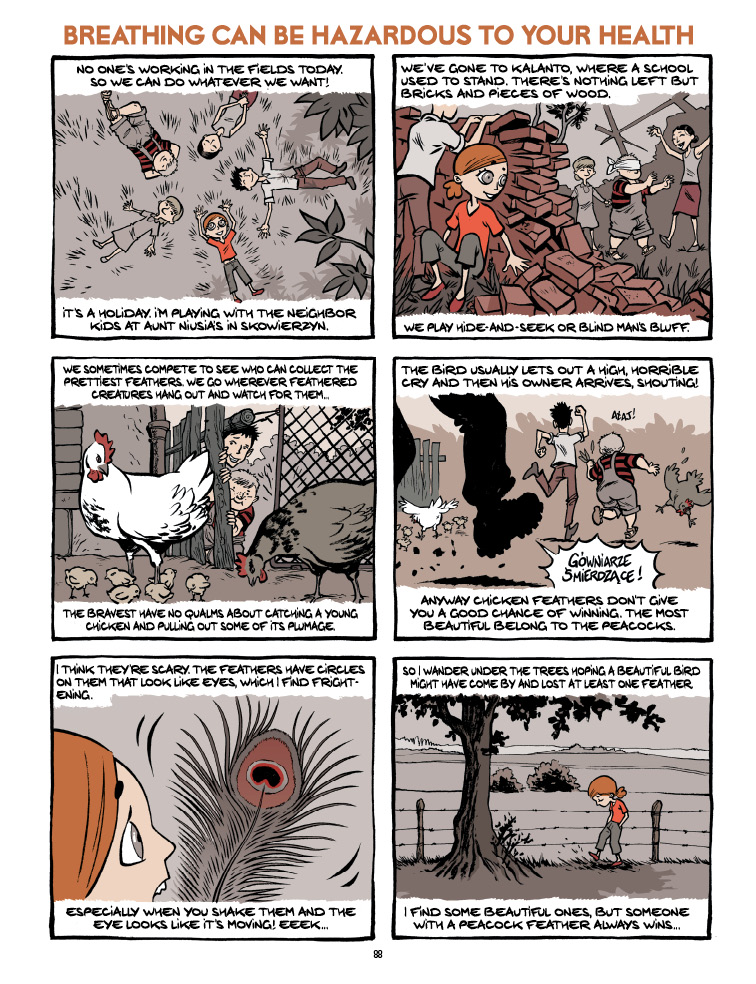

Of course, the first thing that you note when reading a graphic novel is its visual style. Here, Sowa’s partner Sylvain Savoia has employed a childlike style that is not too cartoonish. It perfectly captures Marzi’s sometimes fantastical view of the world around her. Savoia employs muted, drab colors no doubt in an effort to convey the mood of the time in which Marzi grew up. Second, readers will most likely be struck by the poetic nature of Sowa’s writing. That she tells her memoirs in a series of vignettes only lends her reflections on these events to a poetic approach. Robbed of their accompanying images and laid out in verse form, we would still be left with a strikingly beautiful account of her life.

Numerous themes are at play throughout Marzi that lend themselves to theological discussion. Marzi’s religious upbringing is obviously chief among them. We see priests standing beside the workers who strike for their rights. We see rural Polish devotees who claim to see the image of the Virgin Mary in a school window. More interesting than these, however, are Marzi’s own theological questions and speculations. What does God look like? How does God relate to the world? How does God forgive or punish sin? Marzi shows readers the ways in which faith, like communist rule, can oppress but also provide liberation, meaning and hope for its adherents.

Of course, the themes of freedom, oppression, and economic opportunity and (in)equality also demand theological reflection. There is clear economic inequality in Marzi’s experiences, which is all the more ironic against the background of a system that purports to be founded on ideas of equality. The contrasts between the rural and urban settings in Marzi are fascinating as well. Given my own ignorance of that time and place, it seems as if they comprise two completely different worlds, which is not to ignore the harsh experiences that rural dwellers no doubt endured.

Sowa’s reflections on the fall of communism…particularly the ways in which it falls in Poland…are especially beautiful, and not at all like what we perhaps associate with political revolution. It is difficult to read Marzi’s questions at this time and not hear similar questions being posed by so many of our own neighbors today. In what ways will we respond to government failures? What will it eventually take for us to say enough is enough? How and where will protestors occupy to make their voices heard more effectively? For those interested in or participating in the Occupy Movement spreading across the United States, Marzi will no doubt prove to be an insightful, surprisingly fun, and inspirational read.

Marzi (248 pgs., paperback) went on sale in comic book stores yesterday, October 19, and will be in bookstores on October 25. Below is a sample of the novel.

TWEET THIS REVIEW WITH @POPTHEOLOGY BY 6 PM (PST) FOR A CHANCE TO WIN A FREE COPY!