“There is no period so remote as the recent past.” – The History Boys

It’s always hard to remember how difficult it is to make things change. Those of us who celebrated the Supreme Court’s decision last year to allow all same-sex couples to marry across the country may find it hard to remember, or to believe depending on one’s age, that gay folks were politically radioactive just a few short years ago.

For those who want to learn or remember what the dark days of the late 1990’s were like for LGBT politics, Political Animals acts as a pretty good history lesson, showing how four remarkable women made a difference in the California legislature. Between 1994 and 2000, openly lesbian politicians Sheila Kuehl, Carole Migden, Christine Kehoe, and Jackie Goldberg were elected to the State Assembly, and created the first LGBT caucus in the body. In the process, they were able to pass an anti-discrimination/anti-bullying law for gay and lesbian students, include crimes against gay and lesbian people in the state’s hate crimes act, create the first domestic partner registry in the United States, and, vote by vote, expand its rights until all state laws pertaining to heterosexual marriages were valid for same-sex couples. These incremental moves were prior to the much higher-profile Proposition 8 cases that helped launch the final push for same-sex marriage in the country.

Political Animals, which premiered at the Los Angeles Film Festival this past Saturday, and was directed by Jonah Markowitz and Tracy Wares, is both a celebration of these four remarkable women, and a reminder of the importance of studying the recent past.

The film is more exciting than you might think. Along with biographical profiles of and interviews with the women, who are a fascinating collection of political characters in their own right, much of the story advances through floor debates on the various issues they raised before the California Assembly. I know what you’re thinking: “Watching floor debates? There’s a reason why C-SPAN is endorsed by insomniacs everywhere.” But the debates really are exciting. These women are whip smart, and to watch them eviscerate their opponents, mostly white men quoting the Bible, is entertaining political theater.

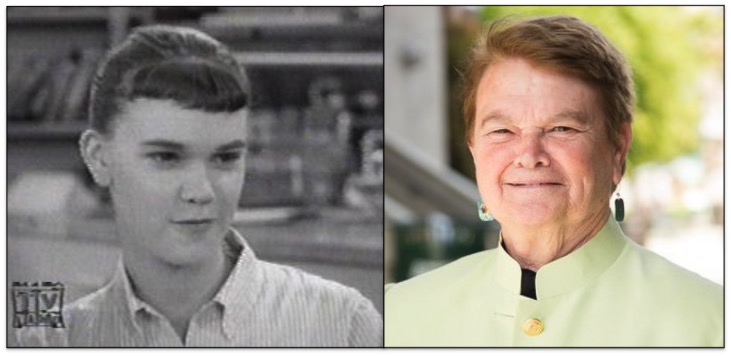

The first legislative lesbian was Sheila Kuehl, who was already nationally known from her role as brainy teenager Zelda Gilroy on The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis. The intelligence she showed on this TV Land classic wasn’t an act: she was admitted to UCLA at age sixteen and later went on to Harvard Law School. She got out of acting in part because once she was too old to play a “tomboy,” directors and producers thought she was too butch to play a leading lady. She came out during the women’s movement in the 1970’s and made a name for herself as a legal advocate for women’s and children’s rights. When she was elected to the California legislature in 1994, she was advancing the rise to power of the gay and lesbian community that had been halted by the death of Harvey Milk in 1977 and the anti-gay onslaught of the religious right in the 1980’s.

Being the only openly gay member of the legislature at the time was a study in persistence. Kuehl had to introduce the nondiscrimination act for lesbian, gay, and bisexual students over five sessions, from 1996 to 2000, before it finally passed. The most infuriating vote was in 1999, when, after an impassioned speech from Kuehl talking about the discrimination she had encountered at a sorority at UCLA, the bill failed by one vote. A small compromise in language the next year allowed it to pass.

Eventually, Kuehl found herself joined by Migden, Kehoe, and Goldberg, and the first openly gay man in the Assembly, Mark Leno. What were once fringe issues became mainstream, until the California legislature became a model for defending the rights of LGBTQ people. Many people don’t remember this, but under the leadership of this group, California actually passed same-sex marriage as a right in both the 2005 and 2007 legislative sessions. It was only because of the veto of then-governor Arnold Schwarzeneggar that the bill did not become law.

This film is a good civics lesson for those who don’t understand our political/legislative process. Elected representatives have to take up issues and bring them up over, and over, and over again. Over time, colleagues begin to trust good leadership (both Kuehl and Kehoe eventually became Speakers of the assembly) and sign on to what were once controversial ideas. It takes time and deliberation. It takes building power through reliable and growing blocs of voters. It takes collaboration between interest groups. It takes horse-trading between legislators. It takes public pressure in the form of contacting legislators, raising awareness, and public demonstrations.

We don’t do a very good job educating our citizens on how the process actually works, and many continue under the delusion that change is easy, or that it can be enacted in one election. When it turns out to be hard, when it turns out to take multiple elections, decades of work, and sometimes generations, to make real, lasting change, people declare the system to be broken and stop participating.

But this is democracy. It’s all we have. If the system is broken it’s because we haven’t cared enough about it to make it function properly. By most measures, state legislatures and the U.S. Congress and Senate are polling in popularity somewhere between sewer rats and malaria. It’s too bad, because Kuehl, Migden, Kehoe, and Goldberg—these four happy warriors of state politics—make legislating seem like grand, meaningful, and courageous work. Maybe they can inspire us to reconsider and reinvest in our governing institutions.