During the recent holiday season, I read three books that could not have been more different from each other, even as they each had religion/religious belief as a central theme. One is a post-apocalyptic novel about a group of monks, the second a novel-length letter written from a dying, elderly pastor to his young son, and the third a satirical novel that is a twisted take on The Breakfast Club set in a version of hell like none we have ever seen before. Read on for a brief snapshot of each.

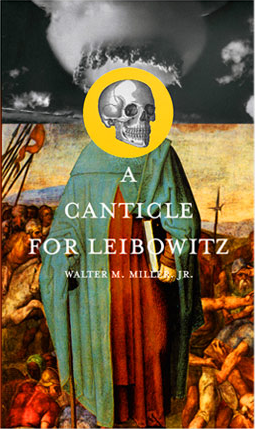

A Canticle for Lebowitz: This one had been on my to-read list for a very, very long time, and it’s better than I could have hoped. It tells the story of the Albertian Order of Lebowitz, a post-apocalyptic group of monks trying to make their way in a devastated world. Divided into three parts, the novel takes place, first, a few centuries after a global nuclear disaster that essentially blasts humanity back to the dark ages. In the second part, centuries have passed and the survivors soldier on in an attempt to re-capture cultural and scientific advances. This part concludes with a promising discovery but also the threat of war. In the concluding section, centuries have passed and while humanity has regained its technological and scientific prominence, it still hasn’t learned how to avoid assured mutual destruction.

This is an important book as it echoes our tendencies to repeat our violent mistakes on both local and global scales. It does capture the role that religion has played in the preservation of civilization and culture, but, on the other hand, it also reveals the ways in which religious bodies (communal and individual) have been complicit in wide-scale destruction and devastation. If we look closely at recent national and global political events, we can hear dangerous echoes of Walter M. Miller Jr.‘s brilliant Canticle.

Gilead: One of my older and wiser minister mentors and close friends told me that he wanted his grown children to read Gilead to get a better understanding of what their “old man” keeps going on about in regards to his religious life. It wasn’t the first time I heard him praise Marilynne Robinson‘s critically-acclaimed novel. It’s such an important book for people of all religious persuasions (or none) to engage. It the novel-long letter to his son, Rev. John Ames explains a bit about his minister ancestors (particularly his grandfather and father), the hard lives they lived, and the disagreements they endured. He writes at length about meeting his second wife, his son’s mother, at such an old age and the ways in which she inspires him. He also goes on at great length about his best friend and colleague’s son (and his namesake), Jack Boughton. While this section of his letter might seem distracting, if we pay close enough attention, it too sheds light on his relationship with both the wider community and his own son to which he is writing.

So much of Robinson’s writing recalls Cormac McCarthy, which is just about the highest praise I could give her work. She reveals that religion and religious practice do not have to be divorced from intellectual pursuit, despite what contemporary examples may dictate. At the same time, religion here is no easy source of consolation or a means through which to answer all of life’s problems. In fact, it might just complicate them. Either way, we should all be so lucky to have had a minister like Rev. Ames in our lives.

Damned: Maddy Spencer is the daughter of billionaire parents (a father film producer and a mother superstar actress). They have homes and servants around the world and take a most liberal approach to child rearing (they engage in frank sexual discussions and frequent drug use). However, these aren’t her biggest problems. Young Maddy is dead and in Hell. Chuck Palahniuk‘s latest novel follows Maddy as she explores the disgusting regions of hell (the Dandruff Desert and Mountain of Toenail Clippings, for example) in an effort to figure out just her new surroundings, how she really got there, and if there is any way out or of improving her lot in the afterlife.

The genius of Palahniuk’s book is that he uses the absurdity of religious belief to critique the absurdity of so many “secular” alternatives to that belief. Maddy may be trapped in hell, but at least she is not stuck in a yurt with her hypocritical mother. At the same time, Damned is a scathing critique of the mega-rich, superstar lifestyles that he previously sent up in Tell All. Like most all of Palahniuk’s work, this romp through hell is simultaneously laugh-out-loud funny and disgustingly horrific.