Editors’ Note: This article is part of the Patheos Public Square on The Spirituality of Children. Read other perspectives here.

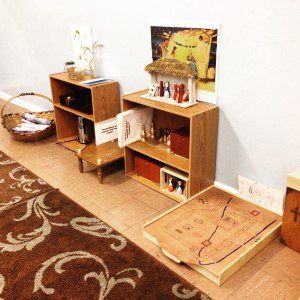

In the hot depths of the summer of 2002 I trudged up many narrow steps to the third floor of our new church. The stairway was steep and just before I caught my breath and landed in the light filled enormity of the attic, I turned to the right and entered into a room that felt, in its diminutive stature, to be the size of a postage stamp. All around the edges of the room were small bookshelves filled with painted wooden figures, baskets, little boxes with paper cutouts, a small altar, and candles. This was the atrium, and it has been center of my world ever since.

Sofia Cavaletti writes, in Religious Potential of the Child, “It is a fact that the child seems capable of seeing the Invisible, almost as if it were more tangible and real than the immediate reality.” (43) A devastating indictment of an adult world, a culture, of me even, about which St. Paul writes, “For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse.” (Romans 1:19-20) Paul goes on to describe how every person labors to suppress what is so profoundly known. If God himself had not intervened, none of us would face Him. But tragically, having once had my own steps turned in His direction, I don’t immediately help others along the way. My days are a catalogue of missing the depths of God’s work, and helping others to miss it, most especially the child.

I looked around the room that first day and tried to understand what sort of work would be undertaken in this small, spare space. Little children would come in, and the Catechist would say a few words, give a short lesson, and then the children would be given freedom to “work” with all the figures and boxes and paper cut outs. One child might take out a clip board and trace a simple line drawing of a man sitting, holding a pearl in his hand. Another might take a green wooden circle with a fence round the edge, and move the white wooden sheep in and out of the fence. Another might paste construction paper cut outs of a chalice, paten, and cross onto another larger paper. To the adult, sitting cross legged on the floor, the work of the child appears to be a mystery, a realm unfathomable.

In the evangelical world “training up children in the way they should go” has come to include a lot of bright colors, a lot of sure fixes that are guaranteed to bring each and every child to a sure and verifiable salvation. The story, the video, the craft, the snack, the ‘be good because Jesus is good’ is the standard. Sunday School Teachers are burdened with the job of making sure the children go away with something, sometimes anything, sometimes the wrong thing.

But Jesus himself said, “Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them.” (Matthew 19:14) And everyone standing around him didn’t know what he was talking about. Certainly I, sitting cross legged on the floor week after week, struggling to speak about Jesus to little children, have wondered and wondered how not to be a hindrance. Hindering is what I do. It is who I am. Where the catechist’s “work” is to sit and not get in the way, my years of laboring have been a catalogue of failure.

The work of the child is clear and open. He knows that God exists and that He can be known. Writes Cavaletti after describing an atheist attempting, unsuccessfully, to deny the existence of God to his daughter, “In the religious sphere, it is a fact that children know things no one has told them. An impressive example, recounted earlier, is that of the little girl who recognized God as maker of the world. Listening to her father’s explanation, she felt in some sense betrayed by his words without having the ability to defend herself; it was enough for her father to pronounce the word ‘God’ for the girl to realize what she had been searching for and she clasped it with infinite joy.” (42) This has been my own discovery, as child after child has come to sit at my prayer table and been asked if he or she would like to pray. The head bobs down, glued to the floor, and words, halting and stuttering, pour out to the creator of the world. And God, whose work and words do not return empty, speaks right to the center of the child.

The work of the Catechist, of every adult that comes close to the mystery of the child, is much less straight forward. For years I have written about work. I have struggled to “let my words be counted”. I have tried to go back to the place I was as a child, standing in an open field watching a storm cloud roll in, knowing, as surely as my bare feet luxuriated in the silky dust, that God was God and that I belonged to him.

In a world where everything is so much a hindering of children, a confinement of the child to the physical safety of adult comfort, I have discovered that the mysteries a child can see and perceive with such ease are there for me as well. What is most essential? It is the same thing for both of us–that God is there, that He created everything of wonder and beauty, that He himself came in human flesh to call his own sheep by name, to lay down His life for me.

As the years have wended their way by, I have moved out of that postage stamp room and have new fine capacious atria, filled in large measure by my own six children. As soon as a child is just past toddling, and is beginning to speak, and discovering the control of hands and feet, that child is welcome to come in and work, to chew on the mysteries of the gospel and the love of God. And I still stand around with my “encumbering person”. I count my words out cautiously, and keep my eyes open for the deep joy of the child.