This morning is a mashup of the resurrection. Psalm 17 is laid out alongside Job 19 and the awkward bit of Luke 20 about the poor woman whose seven husbands all died. The problem for me is that I love Job 19 so much that everything I try to say about it always sounds sappy. Whereas, I loath the Sadducees for coming up with such a ghastly theoretical scenario.

So there’s a woman, they say, and she marries one of seven brothers. And the poor sap dies leaving no children, as men are often in the habit of doing. And so, according to the law, the second brother marries her, in order to provide children for his brother. But being weak and useless (that’s just my own addition) he also dies. And so they all do, leaving her a widow with no children, having endured seven worthless husbands. Then she finally dies, and now, Jesus, whose wife is she?

The point being that any belief in the resurrection is just stupid. Which, if you’ve had to marry seven weak men who just die on you, one after the other, why would you want to go on living forever? Is heaven just some bleak recapitulation of earth? Will the disappointing marriages go on forever?

Of course there is no life after death, postulate the Sadducees. Who could ever untangle the web of relationships, the vortex of sin, the failures of mortality?

It’s a nasty question because Jesus is heading swiftly along towards his own death, which the Sadducees, at this point in the text, are working assiduously to bring about. They want him dead and gone forever, and who cares what happens to them when they die. He is ruining their best lives now.

I’m reading a really funny book by Nora Ephron, who I think is the person who writes all the chic flick movies, although I’m not entirely sure, called I Feel Bad About My Neck. On the back is a picture of her shrouded in a capacious turtlenecked sweater, so that you absolutely can’t see her neck. The book is about how awful it is to age. I don’t think she would want to say, “get old.” Aging is bad enough. Middle Aging is even worse.

You age, and then you die. Or maybe you just die. Everyone does. Even though no one wants to think about it or talk about it. And yet, we all die. In a hundred years, probably many fewer, I won’t be around and you won’t be reading this blog. My children will be old and some of them will be gone. Maybe I will have grand children and great grand children hanging around, who will reminisce to each other about that ancient phenomenon, The Blog. There was this thing, they will say, where people wrote whatever ghastly thing was on their minds, and just put it up, and there it was, no editing or anything.

The point is, I will die, and so will you. And then what? It’s not a new question. Surely this isn’t all there is? But to think that there’s more must be the stuff of unicorns.

So argue the Sadducees. To show the absurdity of such belief they drag a woman through seven marriages and hope to trip up Jesus.

Jesus who will shortly die, so that all of them might live. Jesus who knows the scriptures better than they do, as if every line holds some fragmentary trace of himself—his death, his resurrection. There will be a resurrection, he patiently explains, because Moses addressed the voice coming from the burning bush as the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. “Now he is not God of the dead, but of the living, for all live to him,” says Jesus, driving the point home.

And so everyone is quiet and doesn’t say any more but waits for another opportunity to entrap him.

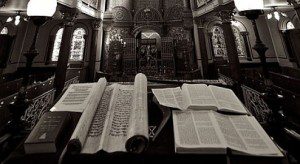

The problem with the Bible, overall, is the immediacy of it. The voice from the burning bush speaks in the present tense. Moses, living so long ago, so far removed from the troubles of the present day, faces a God who is alive in every moment, who is unchanging, able to stop the mouth of mortal humans in every age. Job, whenever it was that he sat in his ash heap of ruin, enduring the “comfort” of his friends, wishing he could die, seems himself to be seeing a vision, thousands of years later, of the cross of all things:

Behold, I cry out, ‘Violence!’ but I am not answered; I call for help, but there is no justice…He has walled up my way, so that I cannot pass, and he has set darkness upon my paths…He has stripped from me my glory and taken the crown from my head…He breaks me down on every side, and I am gone, and my hope has he pulled up like a tree…He has kindled his wrath against me and counts me as his adversary…His troops come on together; they have cast up their siege ramp against me and encamp around my tent…He has put my brothers far from me, and those who knew me are wholly estranged from me…My bones stick to my skin and to my flesh…

He laments, he wishes he had a pen. Whenever he finally climbs out of the ash heap, God having packed the “comforters” off to their houses to persecute someone else, he finally gets one, and something to write on, and the thing that he writes is the overturning of death:

Oh that my words were written! Oh that they were inscribed in a book! Oh that with an iron pen and lead they were engraved in the rock forever! For I know that my Redeemer lives, and at the last he will stand upon the earth. And after my skin has been thus destroyed, yet in my flesh I shall see God, whom I shall see for myself, and my eyes shall behold, and not another.

It’s what we say at a funeral, the families weeping, usually silently, as the coffin is wheeled up to the front and left sitting there, bulky, in the middle of the aisle. Or sometimes there is only an urn, a plain box sitting on a table with photographs arranged around it. And mounds and mounds of flowers. Everyone cries and then goes downstairs for lunch.

We tolerate it pretty well, death. We say we hate it, but when it snatches us away, one by one by one, humanity surges along, arguing with each other and God. Dissatisfied, and yet unable to do anything about it.

It was God, really, who, from the moment death first entered the world, took up his pen to write out the resurrection, line by line, word by Word. When you finally awake, will you even recognize the likeness?