Don’t worry, I’m not going to go on blathering about The Lord of the Rings and The Great Mortality. I have three other important books for you today.

The First Book

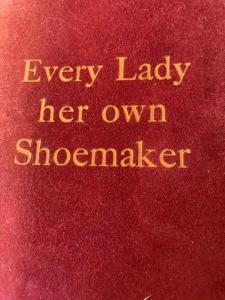

In the height of covid, I managed to acquire a clever little book called Every Lady her own Shoemaker or A Complete Self-Instructor in The Art of Making Gaiters and Shoes by A Lady. It’s all about how to make a nice pair of shoes. All you need is Patent last, Instep block, Tin sole pattern, One awl, Two Saddler’s needles, One ball of shoe thread, Shoemaker’s wax, and a Shoe-knife. All of which you should be able to get for about 80 cents, so says the author in the year of our Lord 1856. There is also this extremely prescient point made right away before all the instructions begin:

One advantage in making shoes is, that the fashions do not change. A last, if once purchased, will answer a lifetime. The same last may fit several in the same family; or if each family does not wish to buy one separately, they may joing their neighbors and have one in common: still we prefer to have one of our own.

Do we indeed? I guess, amongst all my other troubles, I should go and look up what a “last” is. While I’m doing that, you might meditate on this astonishing revelation:

It takes but a short time to make a pair, and as every lady can work equally as nice as any shoemaker, and also as the number is very small who are not obliged to practice economy and retrenchment in their expenditures, we though maky might like to learn how to make their own shoes, if the knowledge was only brought within their reach–hence the following pages.

This must be unequivable, for, as we all know, if we all know better, we will all do better. So anyway, on to more pressing matters. Those two book reviews I wrote this summer are out from behind their respective paywalls, and as I am extremely busy with not only pondering the cunnundrum of whether or not I should begin at once to make a pair of shoes, but also writing a pile of other articles, teaching a teenage boy how to actually do laundry, and petting the cat, I will link them here for your own edification and amusement.

The Second Book

The first is about The Book of Longings. Here’s how it begins:

**Editor’s Note: This article contains spoilers for The Book of Longings: A Novel**

“He reached out his hand, a laborer’s hand. Thick knuckles, calluses, his palm a terrain of hardships.”1 This is the moment Jesus enters the narrative of Sue Monk Kidd’s best-selling novel, The Book of Longings. Ana, who (spoiler alert) becomes his wife after suitable trials and tribulations, has tumbled to the ground in a near faint in the marketplace of Sepphoris where she has just been affianced by her father to an elderly, repulsive scoundrel. It is the first century and Ana is the daughter of the chief scribe of Herod Antipas. She is fourteen years old, literate, precocious, full to the brim of longing to know and accept herself. As such, she is the ideal heroine for such a time as this. By which I do not mean the ancient time of Jesus, but our age, our time — the twenty-first century.

In The Book of Longings, Sue Monk Kidd paints a monochromatic spiritual landscape, tediously rehearsing the contours of feminine longing. As the story unfolds, her characters near perfectly portray the values, the assumptions, the hopes, and the expectations of now.2 If a stranger to this place and time were to require a primer of the ideal person, I would hand her this book. Let’s look together at that cultural icon — not Jesus but Ana — and her journey to discover not just herself but “the largeness” within her that “would not shrink away.”3

Ana — Deceiver, Overcomer, and Mary Sue. My children recently introduced me to a name for a character type in entertainment — comics, movies, sitcoms, novels — that I kept seeing but lacked words to describe. The personality is called a ‘Mary Sue’ and is a technical term for, to quote Infobloom,

a character in a work of fiction who exists primarily for the purpose of wish-fulfillment on the part of the author. She plays a prominent role in the work, but she is notably devoid of flaws or a complex personality, and she usually represents the pinnacle of idealized perfection. All of the other characters love Mary Sue, because she is extraordinarily helpful, talented, beautiful, or unusual, and she often drives readers absolutely crazy because she is one-dimensional and too idealized to be realistic.4

The Urban Dictionary points out that the existence of a Mary Sue often ruins the work, usually because they are able to “defy logic to simply display how amazingly radiant they are.” Some authors will give the Mary Sue a flaw “that is actually just a stale trait in disguise.”5 Whether or not Sue Monk Kidd has wedged herself so forcibly into The Book of Longings, there can be no doubt that Ana as a personality is flat and lacks any character development. She faces no challenge that changes her from one kind of person to another. She never fails to fulfill any of her desires. All the other characters orbit around her to reveal her brilliant longing for herself.

Her “flaw,” which complicates only other people’s lives, is that she often lies and deceives those around her. As the daughter of an educated Herodian scribe, she has been taught to read and write, and she possesses a trunk full of her own self-authored scrolls. Preserving and propagating her own writing, from the first page to the last, is her chief concern. Such a weighty task necessitates both lying and subterfuge as she conceals her scrolls in the room of her aunt, and then in a cave. In the end, being an old woman, she buries them in the ground in Egypt. Besides her own writing, her most beloved possession is an incantation bowl in which she inscribes her longing for herself:

Rising, I took my incantation bowl to the small high window, where skeins of light fell. I rotated the bowl in a full circle, watching the words move inside it, rippling toward the rim. Lord our God, hear my prayer, the prayer of my heart. Bless the largeness inside me, no matter how I fear it. Bless my reed pens and my inks. Bless the words I write. May they be beautiful in your sight. May they be visible to eyes not yet born. When I am dust, sing these words over my bones: she was a voice. I gazed upon the prayer and the girl and the dove, and a sensation billowed in my chest, a small exultation like a flock of birds lifting all at once from the trees.6 (emphasis in original)

Part of Ana’s anxiety is that she has made a “graven image” of herself in the bowl. Improbably, she doesn’t worry about being stoned for breaking the law, rather, she is afraid that the image in the bowl will someday be destroyed. The image of herself is too precious to risk and so she disguises the bowl as a “waste pot” and hides it in her room.7 She ends up carrying this bowl and her scrolls back and forth as she travels around the then known world. The bowl is never seriously in danger, and neither is Ana, because the consequences of her lying never catch up with her. Through a phantasmic succession of events, she evades being married to the old man in the market, she avoids being raped by Herod, and she manages to meet Jesus because her parents allow her to roam around the Galilean desert with a servant. Once she is married to Jesus she brashly acclimatizes herself to his poverty. Using herbs, she successfully avoids having a baby, and when she finally does give birth, the child — Susanna — conveniently dies. In Egypt, she cleverly assists her aunt Yaltha to find a long-lost daughter, and then escapes to a monastic community called the Therapeutae. And finally, with impeccable timing, Ana escapes the Therapeutae in a coffin, arriving in Jerusalem just in time to see Jesus die on the cross. Though all her life is a tribulation, her own personality is never changed. Rather, her immutable and luminous true self is ever more rapturously displayed to herself…read the rest here!

The Third Book

And the second is about Beth Allison Barr’s Biblical Womanhood book. Here’s how that one starts:

“Go, be free!” concludes Beth Allison Barr in her recently released, best-selling book, The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth.1 In the intersection of her life in the classroom and the strictures placed on her by her local church, her beliefs about women radically shifted. Eventually, after a difficult conversation with the theologically unbending complementarian elders at her Southern Baptist Church, Barr and her husband, the youth pastor, were asked to leave. “This book is my story,” she writes, “a white woman whose experiences as a pastor’s wife and scholar have led me to reject evangelical teachings about male headship and female submission. I am fighting against patriarchy for women.” 2 Part medieval history, part personal narrative, and part examination of the condition of women in complementarian circles, Dr. Barr (a history professor at Baylor University) applies a feminist hermeneutic to Scripture and history. She purports to discover a malign patriarchal inclination, if not an actual conspiracy by complementarians, to write women out of the Bible, out of the church, and back into their homes to their highest calling by God as wives and mothers.

While Barr raises essential questions about the identity and role of women, her answer to what she perceives is the irredeemable evil of the patriarchy — to “Stop it”3 — is at the very least unsatisfying, if not impracticable, and, in the long run, theologically frail. Barr’s misrepresentation of biblical inerrancy, her definition of the patriarchy, her interpretation of history and the Bible, and her proposed solution, though emotionally evocative, offer a bleak ideological vision for women in the church and home. Ultimately, there are grave theological and historical problems with her work.

DEMOLISHING THE BIBLICAL CASE FOR PATRIARCHY

Barr, taking her lead from Judith Bennett, defines the patriarchy as “a general system through which women have been and are subordinated to men.”4 In Barr’s experience, this patriarchy has been articulated from many pulpits in biblical terms. “Women,” she writes, “were called to support their husbands, and men were called to lead their wives. It was unequivocal truth ordained by the inerrant word of God.”5 She finds this view troubling.6 Refuting Albert Mohler’s belief that “the pattern of history affirms what the Bible unquestionably reveals — that God has made human beings in His image as male and female….a beautiful portrait of complementarity between the sexes, with both men and women charged to reflect God’s glory in a distinct way,”7 she believes that Christians are actually “pretty late to the patriarchy game.”8 For Barr, there is no real difference between a biblical patriarchy — what many call complementarianism — and the kind found in ancient texts like the Epic of Gilgamesh, in which, against her own inclinations, “the prostitute Shamhat seduces Enkidu.”9

While admitting that “patriarchy exists in the Bible because the Bible was written in a patriarchal world,” Barr explains that the New Testament writers actually meant to undermine and subvert all patriarchy, not just its corruptions.10 Predictably, she bolsters that assertion with Galatians 3:26–28 and Sarah Bessey’s declaration that the “patriarchy is not ‘God’s dream for humanity.’”11 Then, in a series of “What if” questions, Barr demolishes complementarianism as she has defined it. “What if Paul never said this? Just like with the household codes, what if we have simply misunderstood Paul because we have forgotten his Roman context? What if we have confused Paul’s refutations of the pagan world around him with Paul’s own words?”12

Instead, she claims, Paul subverted pagan household codes and replaced them with a functionally egalitarian system within which men and women submit to each other,13 and women are able to hold the same church offices as men.14 Barr takes it as a given that Paul names Junia as an apostle in Romans 16,15 and that Phoebe, to whom Paul entrusted the letter of Romans, is not merely a “servant” but held the office of Deacon.16 All of this constitutes proof of Rachel Held Evans’s claim that Paul meant to “remix” Roman household codes, eradicating all patriarchal hierarchies.17

Turning to the question of Bible translation and inerrancy, Barr observes that the word “marriage” is not used in the Hebrew manuscripts. The translators of the King James Bible put it there, perhaps for nefarious reasons.18 They employed the word “wife” rather than “woman” because Reformation theology relegated women to the narrow sphere of home, husband, and children.19 Furthermore, she argues, complementarian Bible translators chose the use of male pronouns to refer to groups that include men and women.20 Finally, she claims, “the early twentieth-century emphasis on inerrancy went hand in hand with a wide-ranging attempt to build up the authority of male preachers at the expense of women.”21

The Historical Case Against Patriarchy

Barr begins each chapter with a personal example of how she experienced damaging patriarchal complementarianism — in the classroom with a misogynist student, for instance, or enduring a women’s retreat, or extricating herself from a relationship with a Bill Gothard disciple — interweaving those experiences with her expertise, the Middle Ages. Though women at the close of the medieval period were poised to settle into more spacious rooms, the Reformers read the Bible in such a way that hammered the nail into the coffin of women’s freedom.22 In fact, Barr argues, though women had to essentially abandon what made them distinctly feminine — their sexuality, their children23 — nevertheless the church welcomed them “to preach, teach, and lead throughout the medieval era.”24

Using the examples of Margery Kempe, Hildegard of Bingen, Mary Magdalen, Brigit of Kildare, and others, Barr avers that women did not identify themselves in the categories of Evangelical women today — as wife, mother, homemaker, and under the authority of a male pastor and husband. On the contrary, not only did they enjoy greater economic independence than their Reformation counterparts, they devoted themselves to God by entering communities of women, and sometimes ministered alongside men. Barr tells the story of fifth-century Saint Paula, who…read the rest!

And now, if you will excuse me, I will go on about my day with usual futility.