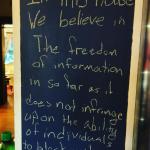

A visual representation of Lasch’s “Consumer-in-Chief”

To pace myself through Bjork-James’ The Divine Institution, which is a short but hard read because the lens by which she is evaluating American conservative evangelicalism is, by her own admission, Intersectionality, the least helpful way to understand anything I think, I picked up a copy of Christopher Lasch’s Haven in a Heartless World. As far as I can make out, Lasch was not a Christian or anything, but he was a historian (such an important occupation these days, even for women) and a student of culture. He appeared to be neither a conservative nor a progressive but was able to thread the narrow way without falling into the pits on either side, and to aptly describe the lay of the land, as it were.

Several bits lept off the page yesterday, as I was taking a much-needed break from Bjork-James’ gotcha lines like:

The fact that this change in worship style coincided with an increasing emphasis on biblical literalism and the patriarchal family helped at times to obscure the conservative nature of evangelicalism. Informants frequently told me that worship—as a chance to experience a direct connection with God—is just as important as sermons to their church experiences. In many ways, evangelicals first seek authentic connection and feeling with God, in making God real in their lives. The theological tradition they are introduced to also tends to shape a particular political perspective, and emphasizes a particular understanding of the family. pg. 28

Contrast that with Lasch:

Still another source of tension was the change in the status of women which the new family system required. The bourgeois family simultaneously degraded and exalted women. On the one hand, it deprived them of their traditional employments, as the household ceased to be the center of production and devoted itself to child rearing instead. On the other hand, the new demands of child rearing, at a time when so much attention was being given to the special needs of the child, made it necessary to educate women for their domestic duties. Better education would also make women more suitable companions for their husbands. The new domesticity implied a thoroughgoing reform and extension of women’s education, as Mary Wollstonecraft, the first modern feminist, understood when she insisted that if women were to become “affectionate wives and rational mothers,” they would have to be trained into something more than “accomplishments” designed to make young ladies attractive to prospective suitors. Early republican ideology had as one of its main tenants the proposition that women should become useful rather than ornamental. In the categories immemorialized by Jane Austen, women had to give up sensibility in favor of sense. Thus bourgeois domesticity gave rise to its antithesis, feminism. The domestication of women gave rise to a general unrest, encouraging her to entertain aspirations that marriage and the family could not satisfy. These aspirations became an important ingredient in the so-called marriage crisis that began to unfold at the end of the nineteenth century.

From thence Lasch discusses the rise of the expert class. It came to be that no one could do anything anymore without being told about it by people who knew better. As Bjork-James notes, Focus on the Family came to be one of the greatest sources of expert counsel, among others, for those on the right, while other kinds of experts emerged on the left.

Now, I happen to think that the reason all these experts came to be so depended upon was not because of some kind of nefarious conspiracy of white, racist evangelicals, but because the cultural shifts that happened without ordinary people knowing or thinking about them meant that those same ordinary people really didn’t know how to cope with ordinary everyday life. Women, it turns out, no matter how often they are told they shouldn’t want marriage and children, still often do want marriage and children, but when they get to have both of those things, they have no idea how to inhabit them, nor men either. Then along comes someone who says, “I know how to do this, I’ll help you,” and so, of course, those people listen to them. As the moral assumptions associated with Christianity floated off into the mists of time, all manner of advice flooded into the marketplace, including stuff like Intersectionalism.

But, you know, it can’t be that evangelicalism was one strong, and occasionally over-reactionary cultural voice among others over the last tumultuous century, it has to be that they have no business thinking anything about anything.

And now, if you’ll excuse me, I have to go clean my kitchen, for that work is always there, whether or not any expert or Intersectionalist appears out of the internet to say anything about it. Have a nice day.