Before the shocking headline yesterday about MLK, I had been wandering around all weekend enumerating to myself a strange and tragic predilection of being human. I thought about it a lot in the early days of #metoo, and at other times here and there, and it is strange that I happened to remember it right before this weekend’s news.

What it is is the feverish and pitiable way in which a person might endure some great evil—to have been victimized, brutalized, treated unjustly, wounded sorely—and then, in the aftermath, in the outworking of that terrible occurrence, he himself, or indeed she herself, fall into error and sin.

Whereas, the unfailing expectation of all people everywhere is that there will be good people who do good, and bad people who do bad. The lines between these two groups is supposed to be clear and recognizable. We each of us know ourselves to be in the good group. Other people who do bad things are in the bad group. Even by doing a few bad things myself, I never completely move over to the other side.

Every so often some cultural shift or trend comes along to reclassify or re-artciulate who is good and who is bad and then everyone has to shift themselves around to ensure that they remain in the good group. Sometimes whole groups of people fail to do this and then are demonized, systematically ostracized, put into terrible circumstances, and then, if they come out from under the yoke of suffering, the cycle starts over again.

#metoo was one such moment. Men who sexually abuse women are bad. Always. And women are not bad and should be believed. Whereas before, in some segments of human culture, women had always been bad for tempting men.

It was a great relief for many women to be able to say, ‘this happened and it was very bad’ and for many people who had never wanted to think about it before to leap up and agree—‘yes, that was wrong, and no, you didn’t do anything to deserve it. And yes, it is always wrong in every circumstance.’

The trouble is, women are human just like men. That’s the problem with everything. They would like to be treated as human, but so would the men, even after treating many women as if they weren’t human for, well, for as long as humanity has remembered anything. But they are, they are all human.

And therefore have the capacity to be both victim and abuser, to be sinned against and to sin, sometimes before even a few minutes have gone by.

And this is very difficult and hard because we are quite desperate to maintain those clear lines between good and bad. And if someone who is ‘good’ goes around—and I might say, usually these kinds of sins are very small, but are nevertheless sin—and does something ‘bad’ in the aftermath of having suffered, well, we don’t know what to do about it. We don’t want to put them in the ‘bad’ category, and so we have to pretend it didn’t happen, or explain it away, or find some cure that will keep all the lines clearly drawn.

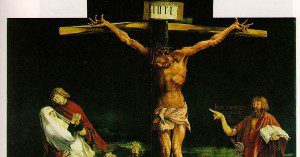

I was thinking about this because Christians are always invited to consider the strange truth that Jesus was able, on the cross, to be both victim and priest. He was good enough to administer the sacrifice—holy, upright, good—and also, in his perfection, able to be the sacrifice—unspotted, unblemished, unstained, pure. This was a remarkable moment in the history of humanity. This had never happened before, and certainly has never happened since, and that’s why he was able to save us.

Whereas we are a perplexing confusion. The cords of sin and death entangle us and there is no clear, pure, perfect victim who doesn’t go around after suffering and contribute to the suffering of others.

I said it is often small. Sometimes it is the small cruelties that are the worst, especially knowing that they arose out of some other original injustice or abuse. A mother who has been shamefully treated and knows it will happen again, and wants to protect her child, might treat that child cruelly as an act of preservation, to keep the child from forming bonds that will ultimately hurt him. And yet the cruel distancing between mother and child, meant, as it were, for love, will stay with that child for, well, it might be forever, and will mean he will evermore relate to others out of those first loving though cruel sorrows. Understanding what happened at first is so important and necessary, but then you still have to cope with him as a grown person, unable to properly attach to other people who might love him. And so there is the good and the bad all mixed together.

This is why we oughtn’t to demand great purity from each other. We ought to find ways to forgive and rectify injustice that leans heavily on mercy. Because we cannot be just. The roots of badness are intertwined so completely around goodness that we cannot perfectly and satisfactorily disentangle them—not as we know they ought to be—in the clear light of day.

Only Jesus can do that. He, by his gentle hand, untangles the mess, by his own blood atones for the horror of sin, by his great love comforts the broken and wounded, and by his perfect goodness judges the sinner. He is good, and we are not—none of us—and yet he has the power to take evil, our evil, and work it out for a great and true and ultimately perfect good.