I happened to cut my gum yesterday, while foolishly trying to floss my teeth. The age of coronavirus has shattered me enough that I finally started doing something I should have habituated myself to 40 years ago. I ended up leaning far over my tub, weeping, cursing myself and the darkness, blood flowing out of my mouth. Then I wondered how much blood Jesus would have had dripping out of his. He was struck so many times. He probably had an awful mouthful of warm, sick, salty blood, at various points, and then would have wanted to spit but wouldn’t have had the breath.

I’m not going to go look up a medical account of the crucifixion. I’m sure someone has answered the question, but I don’t really want to know. A lot of questions we might ask do have answers. And some of the answers are, what I like to call, ‘non-essential.’ It’s not ‘how much’ blood fell out of Jesus’ mouth or hands or side, down to the very ounces. Though I suppose we might some day know, after all our own blood has dried up and turned to dust. It is why and wherefore. Why did Jesus bleed and die? What was the purpose?

My gums bleed when I floss because I never floss. Which leads to other, perhaps more ‘essential’ questions—why don’t I floss? Why would I floss now after never flossing before? Why do I have such bad teeth in the first place? Why didn’t I care more sooner? Each of those questions has a prior essential question behind it, many of them leading to inescapable, though usually unacknowledged conclusions, the most essential of which is, I am going to die at some point. Everything before that is kind of vanity, but not all vanity is completely useless, especially if I finally start flossing.

I’m circling around the word ‘essential.’ One of the bedrock assumptions of my approach to children and teaching them about Jesus—which I appropriated from Sophia Cavalletti—is that you need to spend time on that which is most essential. There’s a lot of stuff you can do with children. There’s a lot of hours you can fill. There are a lot of crafts you can do. But it’s better to acknowledge the limitations of time, energy, attention, and frailty. That being so, you ought not spend time on secondary issues. Children don’t need to be hauled out of their warm beds and to church, their parents exhausted from the effort, strung out by life, and then sit around coloring a little picture of Noah’s Ark. You might have one single hour with that child a week. What is most essential? What will you talk about? What will you do?

Similarly, a lot of people in America have discovered that their professions are, from the point of view of the government, ‘non-essential.’ Doctors and nurses, of course, get to go to work—mostly, if the kind of medicine they practice is related to the coronavirus. Grocers, pharmacists, truck drivers, liquor store owners. But not hairstylists, nor the person who owns the lighting store down the way, nor the frozen yogurt place, nor every single school. Almost everything is shuttered as we all stay inside. All the economies that we, as a nation, take utterly for granted have all ceased, for the time being, and every day anxiety rises higher and higher, along with the death count, at least in some places. When we’re allowed to go out again, will we be able to do any of this work? Is some of it disappearing forever?

Turns out that one of the things that is essential is money—not for its own sake, but because without it most of us will starve to death, and also be unhappy. Balancing the very essential question of life, and wanting to stay alive in the short term, against anxiety about being able to stay alive over many many years, is an essential conundrum. It gets right to the heart of eternity, almost.

Anyway, it’s Palm Sunday. And you have to know that I’m going to observe, in my regular annual way, that it is so heartbreaking that what God counts as essential very rarely matches our essential calculations. The thing that I want most is not to have a mouthful of blood—therefore I will either floss to prevent it, or not floss to avoid it, and go back and forth between the two. I also don’t want to die, in any sense, nor feel sad, nor be poor. And I don’t want people to limit me in any of my endeavors. I want more likes on Instagram.

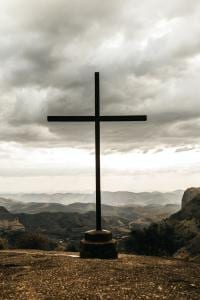

What God wants is for me to grasp the cup that is, right now, temporarily beyond my reach, though not in cosmic terms, and look into its depths, and understand that it should have been me up there on the cross—humiliated, shamed, bleeding, naked—because I had offended against his most holy law. In my very being, my total orientation, I had turned away from him and toward myself. There was no health—none—in me. And yet, though it should have been me, he went there instead.

Looking into the depths of that cup from a far off, I find I am astonished. I almost can’t believe it. I would avoid that experience at any cost, let alone going and doing it for someone else. And yet God—God of all people—who didn’t need to, whose glory and exaltation are so far outside of my small, narrow sphere, took up his cross to go there and endure it on purpose.

I think that astonishment is essential. I think it is the first sip out of the cup of salvation. And it turns out that the sip, though humiliating at first, turns the blood into wine, the mourning into joy, the death into life, this moment into eternity.