Christopher Rodkey, a speaker at PYM14, is Pastor of St. Paul’s United Church of Christ in Dallastown, PAs, and teaches at York College of Pennsylvania, and occasionally for Lexington Theological Seminary. His new book is titled The World is Crucifixion: Radical Christian Preaching, Year C, and he is the series editor for Intersections: Theology and the Church in a World Come of Age, published by Noesis Press/The Davies Group.

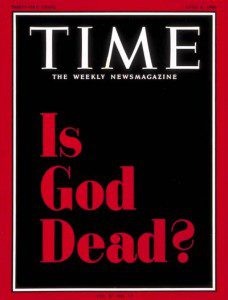

I was interviewed by Time magazine for their special story on the 50th Anniversary of their infamous cover, which read “Is God Dead?” The article ended up only mentioning that I’m editing a new critical edition of Radical Theology and the Death of God by Thomas Altizer and William Hamilton, and I’m totally cool with being name-dropped by Time magazine.

But there is a whole lot more to say.

What is death of God theology or “radical” theology? These are words that are suddenly popular to use and they mean different things to different people. For Altizer, the death of God means that God dying is the overarching metaphysical reality of God, and that every movement of divinity is a self-negation or “death”: Christmas is the death of God as incarnation; the ministry of Jesus is the death of God; transfiguration is the death of God, etc.

For others the death of God is a call to radically rethink what we mean by the word “God,” and to rigorously reflect on the use and abuse of the word itself; that post-Holocaust, post-Christendom, post-modern, post-colonial, queering anthropocene theology must involve a complete evaluation of “God.”

This of course leads to a question whether Christianity could be considered non-theistically, or even as an exercise—as, for example, Peter Rollins has put forward—giving up God for Lent to ask whether anything really changed in one’s faith. If one’s thinking about God, and thinking about humanity, has not changed following the Holocaust, the zero-point for human impact on global climate change, or after Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Chernobyl, we have good reason to believe, or even affirm, that our theology has failed to name and make sense of God, let alone ourselves, in the present.

Thinking radically about God can take many different forms and is not a singular view or methodology. Rather, it is an ethos of doing theology; and in the end radical theology is an acknowledgement that if Christianity in practice is not radical, it is not Christianity, but rather a relic of Christendom and its constituent denominations.

I am often asked by youth pastors and other clergy where a good place to start might be for death of God theology. I’ve always suggested the original 1966 edition of Radical Theology and the Death of God or the edited collection Toward a New Christianity. William Hamilton’s previously published key book for me is titled On Taking God out of the Dictionary. Paul M. Van Buren’s The Secular Meaning of the Gospel is worth reading, but if you can track down his The Edges of Language and a companion article (in the Harvard Theological Review) which deconstructs St. Anselm’s Proslogion, you’ll be set there. Gabriel Vahanian’s Wait without Idols offers a good sense of what he’s about, though I really liked his final book, Theopoetics of the Word. Mary Daly’s Beyond God the Father is the contribution to the canon, but Pure Lust is an incredible experience to read.

When it comes to Altizer’s work, it’s hard to know where to begin if you’re new to the ideas. Lissa McCullough’s essays in her edited book on Altizer’s theology, Thinking through the Death of God, offers the best one can find. The Gospel of Christian Atheism is as good of a place as any to begin, and I found his often-overlooked The Descent into Hell a key text for making sense of his kenotic Christology. Among his “middle work,” Total Presence and The Self-Embodiment of God are key works; and I really enjoyed his more recent The Apocalyptic Trinity.

There is an old black-and-white video that discusses the death of God controversy at its height. You can find the first part of it here and the second part here. From my perspective a key moment happens about one minute in the second part, where the Bible college professor says, while standing in a classroom, that the death of God controversy hasn’t been discussed too much because it just isn’t important. The video then cuts to a group of boys in a 1960s dorm room intelligently discussing radical theology. One observation which I draw is in the background chalkboard in the Bible college professor’s classroom, listing the names of the Old Testament Judges, exemplars of leaders who disclose a warrior-king model of God. This contrasts with the boys speaking about the extraordinary banal, and how theology often says something more about us than it does about God.

And here we have it: the old guard saying that images of God must be entrenched in the past, the young with visionary, exciting ideas.

If we showed this old documentary to our teens, what would their reaction be? And whom would they be appeasing in their answers?

Even though our churches and denominational structures are largely still convincing themselves that Christendom and its God are not dead, we know better. That God never existed anyway, and the more it was worshiped the more it has become evil. We don’t need to dig too far past the front pages of the news to see the church doing stuff as its last gasps of rigor mortis.

The reconstructive act of recovery is what we and our young compatriots are charged with. In doing so—to use William Hamilton’s term—we will become expatriates. How is your youth and young adult ministry teaching the next generation to be theologians who will not earn, nor need, a theological degree or an institutional church, and will neither become nor rely upon an ordained pastor?